essays

Why People Don’t Like “I Love Dick” (Hint: Because It’s About Women)

Apparently, female sexual desire still too much for prestige-TV audiences to take.

The evidence is everywhere. America loves dicks. The Washington Monument, ice pops, Michael Fassbender, and our President, who is undeniably a dick. But it goes back further than that. Here’s a short list of some dicks (both real and fictional) Americans have loved: Christian Grey of Fifty Shades, Justin Bieber, Chris Brown, Don Draper, Stringer Bell, Tony Soprano, Al Swearengen, Will Hunting, Mark Wahlberg’s fake dick from Boogie Nights, Patrick Bateman, Hans Gruber, every character James Spader ever played, especially when he was young, most of the characters Bill Murray’s played, Michael Douglas in Fatal Attraction, Gaston in Beauty and the Beast, Bruce Wayne, Jack Nicholson in Five Easy Pieces, The Shining, As Good As It Gets, and Something’s Gotta Give, Russell Crowe (in life), Sean Penn (in life and in art), Clint Eastwood’s many iconic dicks, like his character from Dirty Harry, and Steven Segal’s entire oeuvre. Dicks aren’t just confined to low culture, either. We love Alfred Hitchcock, Woody Allen (dear God), Bret Easton Ellis, Norman Mailer, Ernest Hemingway, Jay Gatsby, Holden Caulfield, and I’ll say it, Tom Sawyer. He was a dick. We may all like Forrest Gump, but no one wants to fuck him.

So if Americans love dicks so much, why don’t people seem to like Jill Soloway’s new Amazon show, I Love Dick? The show, an adaptation of Chris Kraus’s 1997 novel, stars Chris (Kathryn Hahn) as a frustrated filmmaker who becomes obsessed with a laconic conceptual artist named Dick (Kevin Bacon) while her husband, Sylvere, is at Dick’s writing retreat in Marfa, Texas. She’s not just obsessed with him, of course, but with his namesake body part, and what it might be able to do to her. She starts writing Dick erotic letters, which turns her husband on until she actually sends them. Sylvere’s humiliation turns to rage when Chris starts posting the letters around town in a kind of performance piece of her own. Things devolve from there. Though the setting and plot of the show differs — the book is entirely epistolary and set in New York and California — the show aims to fulfill the ambition of the book, which Jenny Turner has called a “künstlerroman,” that is, the story of an artist’s development.

Reviews of the show have been lackluster, especially considering Soloway’s outsize influence on the current culture, thanks to the success of Transparent. The New York Times called I Love Dick overwrought, complaining that it if you miss a “theme” of the show, the “characters [will] explain it explicitly” to you in due time. The Boston Globe reported that despite their high expectations, “the reality” of the show “is a whole lot less appealing” than had been expected. Matthew Gilbert of the Globe wrote that “at points, it’s as thin as its titular joke, a pun that the script leans on like a fifth-grader with a new command of naughty words.” The Hollywood Reporter called it “messy and not very likeable,” while Variety gave it an otherwise good review but called it “occasionally exhausting.” Notice the gendered nature of these critiques. All sound like they could be leveled against an individual woman, perhaps Chris Kraus herself: she’s messy, immature, pretentious, not very appealing or likeable, and kind of exhausting.

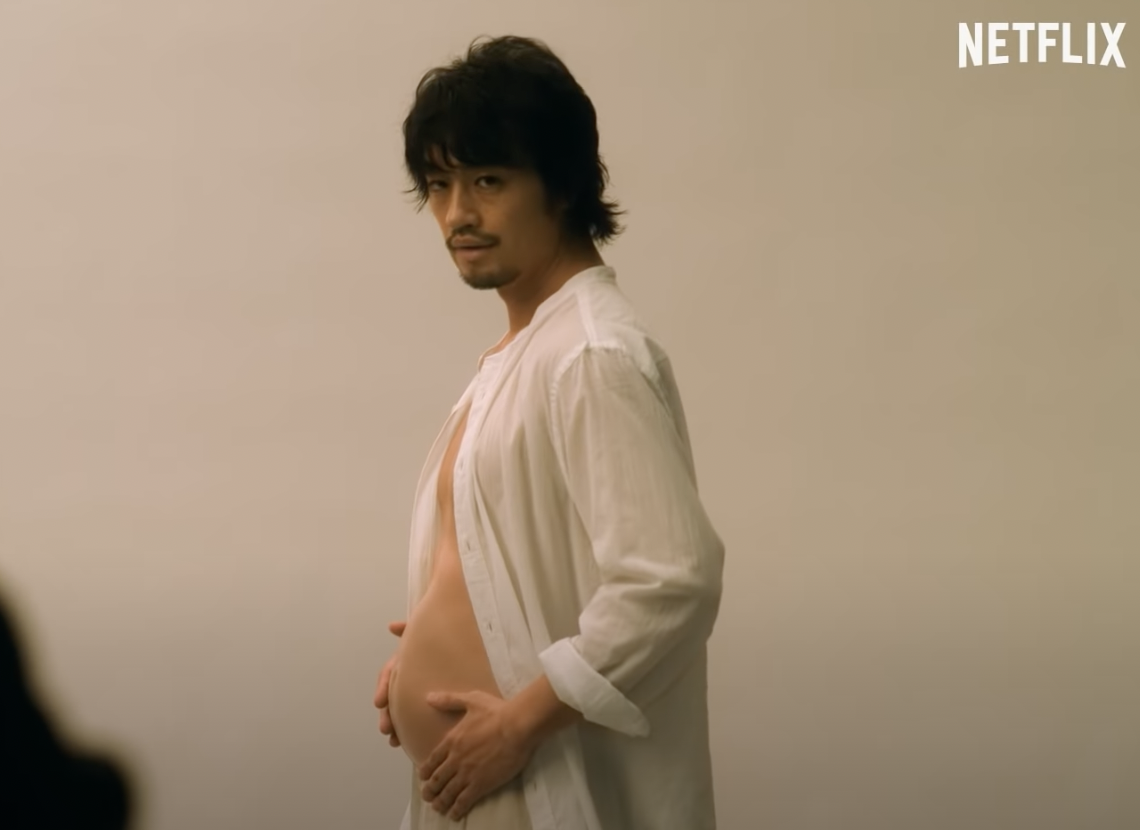

It’s hard to believe that the bad reviews are thanks to the subject material’s sexual explicitness, since so many shows on television today deal with serious, challenging material. Transparent, Soloway’s first venture, loosely based on her own experience of having a parent transition late in life, is nothing if not provocative; it has grappled with issues of gender and sexuality more explicitly than any show before, and has become a huge critical and commercial success by doing so. Hulu’s recent adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, about a patriarchal dystopia, is also a critical and popular success, despite the fact that it contains content at least as controversial as I Love Dick (I would say much more so). The Handmaid’s Tale graphically depicts ritualized rape, female genital mutilation, state-sanctioned murder, and the hostile takeover of the United States government by religious zealots, and people love it. As the long list of ‘dicks’ above shows, we don’t generally have a problem rooting for male anti-heroes, even when they’re mafiosos, pimps, misogynists, murderers, or rapists. Nor does the TV-viewing public have a unilateral distaste for edgy shows with progressive, even radical, politics. Yet a story about a woman with a crush in the desert isn’t gaining traction. Even when Kevin Bacon plays that crush, and you get to see him shear a sheep topless.

Reviews which fault the show for being “unlikeable” and “exhausting” rely on what are by now cliché criticisms of female characters and women in general. These reviews are not only remarkably gendered in their language, but they’re also wrong. I Love Dick is a very good adaptation, and a good (maybe even a great) show. Some people just don’t like it because they don’t like women, particularly women who want and have sex, and particularly the parts they have it with, like vaginas. Soloway recently acknowledged that part of the appeal of Transparent may have been that it starred a man, albeit a man “playing a trans woman.” She told the Times, “I don’t think America understood that at first…I was writing pilots about unlikable women for 15 years, but it took a man in a lead role for me to actually get any attention.” It’s still early days, and I Love Dick may gain a fanbase with time, but the early reviews suggest that — hard as it may be to believe — America may be more comfortable watching a man transition than watching a heterosexual cis-gender white woman desire a heterosexual cis-gender white man.

Reviews which fault the show for being “unlikeable” and “exhausting” rely on what are by now cliché criticisms of female characters and women in general

While Transparent explores gender fluidity, I Love Dick doubles down on a certain kind of essentialist femininity — not the passive kind we’re used to seeing in art — but an essentialist femininity nonetheless. In the first episode, Dick insults Chris’s intellect and artistry. She rages at him but is also titillated. The last episode finds Dick and Chris finally about to hook up, when she gets her period as he is fingering her. In the final shot of the series, Chris’s menstrual blood trickles down her bare legs as she walks through the desert, and we’ve got the iconography of a primal scene: Eve who sinned by wanting — punished by the pain of childbirth and periodic bleeding — is cast into the desert. Throughout most of the series, Dick doesn’t reciprocate Chris’s desire, but she wants him anyway; ironically, almost magically, because he won’t let her know him, she’s able to objectify him in a way that is productive for her art. The artist in Chris has arisen out of her experience with Dick, just as Eve was cleft from Adam’s rib. But this is different, because Eve and Adam wander the desert together once they are cast out of Paradise. When Chris realizes that it wasn’t her desire for Dick (or dick?) dripping between her legs, but rather her menstrual blood, she walks out into the desert alone. Contemporary feminists may be uncomfortable with this final image and the way it closely aligns female desire and agency with the traditional biological markers of womanhood. As Soloway’s other show has amply demonstrated, not all women have ovaries, and not all women menstruate.

Rightly or wrongly, I Love Dick harkens back to an earlier moment in feminism. Transparent is a masterpiece, but it is about gender, family, women, and men. At its heart, it is a traditional narrative in the sense that it’s about the soul’s quest to find its place in the world. Its political valence is queer, not feminist (these vectors intersect but are not the same). I Love Dick is all about women. Its milieu is a very particular, and at this point somewhat historical, feminism. The show captures the moment in which Chris Kraus wrote the novel, in 1997, before gender studies and women’s studies had coalesced in academia, before notions of gender fluidity became widespread, and before intersectionality became a concern of mainstream American feminism. To her credit, Soloway adapts the material in ways that acknowledge the limitations of the original text for today’s intersectional feminist moment: in the novel, Kraus writes from the frenzied perspective of one privileged white woman. Her letters are a screech into the void created by the male intellectuals who surround her but won’t hear her. The Amazon adaptation, however, widens its focus, telling stories from the perspectives of other women with different backgrounds and experiences, and who don’t share the fictional Chris’s privilege with regard to capital, education, or race. For instance, in one of the season’s most powerful episodes, “A Brief History of Weird Girls,” three women besides Chris write letters to Dick, explaining how he has catalyzed their growth and artwork. For one of them, a native of Marfa named Devon (the remarkable Roberta Colindrez), Dick’s macho swagger gave her a model to imaginatively grow with as a young woman who was discovering she was a lesbian (the final episode finds her making art about that process). Compared to the gorgeous ensemble made up by Colindrez, Dick’s gallery’s curator (Lily Mojekwu), and India Menuez as an art historian of porn, Chris is the woman who is the most difficult to identify with, not only because of her privilege, but because of her fecklessness. That the show in general maintains its focus on Chris’s experience, however, suggests that the adaptation wants to preserve the challenge that the original offered to the masculine status quo: it says, look at this woman, watch her, see her do all these things that men have done in art a million times, and feel how you feel about it. Whether you like it or hate it, you will have learned something about yourself.

Soloway has stated that this was her goal, not just to adapt the book, “but [to]…record the feeling of what happens when you read the book.” Kraus herself lauded “A Brief History of Weird Girls,” for “adapt[ing] the phenomenon of the book rather than the book itself.” Just like with Chris’s erotic letters, none of the letters in “A Brief History” are actually about Dick. They’re about the way the women are using Dick to create something for themselves. As Jenny Turner put it in a 2015 review of the novel for the London Review of Books, Dick is “a man-size ‘transitional object’ who happens to be in the way” of Chris’s character. This episode — and the series as a whole — captures that truth for a broader array of women characters than just Chris.

If watching women use Dick for their own growth sounds unpleasant or opportunistic, remember that male artists have relied on female ‘muses’ for just that throughout most of recorded culture

If watching women use Dick for their own growth sounds unpleasant or opportunistic, remember that male artists have relied on female ‘muses’ for just that throughout most of recorded culture. It’s also worth noting that Soloway, creator of a runaway hit for Amazon, still had to go through Amazon’s pilot process in order to make I Love Dick, while Woody Allen, as the New York Times reported, did not, despite the fact that he had never made a television show before, and that his reputation has suffered in recent years after his daughter Dylan Farrow wrote an open letter to the Times recounting her experience of sexual abuse at his hands. When asked about why she was subjected to the pilot process and Allen wasn’t, Soloway responded: “one word: patriarchy.” Our culture views women with suspicion, and hates women who want things. We are comfortable with men who want things, even men like Allen, who have demonstrated in their art (not to mention their real lives) their willingness to desire things which our culture considers aberrant. But a woman wanting, even wanting the thing that heteronormative culture tells her she is supposed to want — dick — is trouble. Women are supposed to be wanted, not to want. Chris wants Dick single-mindedly, the way Hillary Clinton wanted to be president, and our culture finds that objectionable, even gross. Well-behaved women are wanted. Nasty women want things.

I Love Dick may not be perfect, but its reception reveals to us how much difficulty we still have seeing women portrayed as desiring beings. I think the show is about much more than a simple role reversal, but even if all it was doing was putting a woman in the position traditionally held by a man, it would be enough to reveal to us how uncomfortable we still are with women, their bodies, and their desires. John Cusack can hold a boombox outside a girl’s window and we swoon, Richard Gere can stalk a prostitute up a fire escape and that counts as romance, but a woman character writes a few dirty letters to her crush and we’re as creeped out as if she’d just boiled his son’s bunny. I Love Dick, unlike The Handmaid’s Tale, Game of Thrones, or popular potboilers like Law and Order: SVU, does not contain any violence, against women or men. We don’t see any women get raped, or even threatened with rape. We’re never scared that Dick is in any danger. And yet it is clear that the show feels dangerous to many of us, especially when it reveals how fragile men can be when they are treated like women.

Our problem isn’t that the show is about loving dick; it’s that it’s about women loving dick in a utilitarian way, in a way that helps them become more themselves. Chris may love Dick, but that does nothing for him, while it does a lot for her. That’s not a story our culture is used to hearing, and it’s not one we like.