essays

Why the “Good Place” Personality Test Is Better than the Myers-Briggs

The show engages with failure, struggle, and change—which makes identifying with its characters an exercise in insight

First: The Good Place is a sitcom about a woman who ends up in the “good place” in the afterlife by mistake. You should go watch it! First season’s on Netflix. Second season’s not, but use whatever means you like — I won’t judge.

I lied. I’m totally judging — judgment is, after all, what The Good Place is about. You went and watched the show just because you wanted my approval, without even knowing why, and you — what? Pirated it? You’re such a Jason/Tahani.

Recently, artist Noelle Stevenson put forth a theory on Twitter: everyone is a “mixture of two characters on the Good Place.” The theory took off, with fans of the show eagerly adding to the evidence.

I think everyone is a mixture of 2 Good Place characters and mine are Eleanor and Jason

It’s pretty par for the course for people to identify with characters on a TV show — BuzzFeed in particular is famous for its identifying quizzes. And people are always trying to figure out how to break down their personalities to their most essential, atomic bits. It’s how fanciful, unscientific, and fun personality descriptions like the astrology, zodiac, and the MBTI continue to exist. But this particular formula — that everyone is specifically a mix of two characters, no more or less — was unusual and surprisingly effective. Why did it work so well?

I hope you actually did watch the show, because spoilers abound.

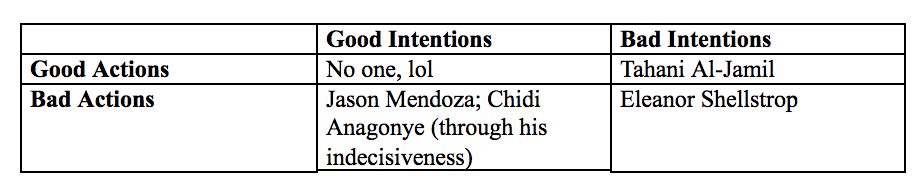

The Good Place is a metaphysical sitcom about morality, and what it means to be a good person. By what rubric should you be judged? What flaws are allowable? What intentions are important? What philosophers are well worth listening to? (None of them, thanks.) All four human characters find out they didn’t get into the eponymous Good Place because of a bad mixture of intent and action. In fact, their rulings were so succinct, I can chart them:

A few of the other characters in play for the “mix of two characters” theory are metaphysical beings: a demon named Michael, and an AI named Janet, which the Good Place wiki calls “a sentient database/personal assistant,” an “operational mainframe” for the Good and Bad Places. So: one made for evil, and the other made for good — although both of them, by the second season, are struggling with their identification with these very concepts.

The “good and bad” dynamic doesn’t pop up that often on personality charts. I have heard people whine that the MBTI is “inaccurate” because “there are no bad types,” and have swiftly avoided these people, those who are so eager to try to definitively figure out who the “bad” among us are through a test with no scientific basis.

Every character is defined by this interplay of action and intention, unconscious instinct and self-aware self-improvement, good and bad.

The alignment chart from Dungeons & Dragons does include evil, but it’s an outlier, and is mainly based on organizing characters for the sake of a game, rather than for self-identification. I’m not saying people don’t identify with it — but the “personality types” aren’t based on personal wrestling with morality. Good characters are motivated to do good, evil characters to do evil. It’s not nuanced — there’s no room for struggle, failure, or trying.

But in The Good Place, all six of the characters are struggling, failing, but trying to be good people. Michael and Janet are especially interesting cases in this. Michael is eager and learning to be good; Janet is contending with feelings, those strange whatsits that often hijack and defy concepts of morality (or, more specifically in Janet’s case, helpfulness).

The Good Place’s main goal, for all its intelligence, is to be funny, so its characters’ flaws are taken to extremes — all the easier to see echoes of them in your own secret foibles and shames.

Eleanor’s like a combination of all those annoying jerks you’ve met who got away with everything and never cared about how any of their actions might’ve hurt anyone. While each one of Eleanor’s actions are annoying and rude on their own — skipping out on designated driver for every work happy hour, ripping a roommate’s super expensive dress, giving someone else’s dog an eating disorder — all of them combined is a particularly potent brand of amoral, selfish jerkishness. In fact, writing that all out, it’s no wonder Michael never believed she’d “get any better.”

Tahani’s rich and famous, so her need for attention is an even bigger maw to fill than anyone else’s. But her entitlement is balanced out by how everyone — including her parents, the people who are supposed to give her attention — everyone, both strangers and family, pass her over for her sister. It’s one thing to be envious of your rich and famous friends; it’s quite another to do so when so devoid of love and so hungry to both give and receive it.

Jason’s heart might be in the right place, but I’m not sure how much that matters when you say, with all seriousness, that you solve your problems with Molotov cocktails. Regular humans just try to solve their problems with regular cocktails, not Molotov ones.

And then there’s Chidi, whose indecisiveness is so paralyzing that, in a test for his soul, he takes almost an hour and a half to choose between two fedoras.

Each character’s flaw is so big and loud that it obfuscates all other parts of their personality. This is part of their problem — part of the reason they ended up not just in the Bad Place, but in the Bad Place to torture one another for (Michael expected) thousands of years. And, to be clear, it was only in the afterlife that the human characters really even became aware of how big their shortcomings were. Their lack of self-awareness and understanding was one of the biggest reasons they ended up in the Bad Place.

The exaggerated nature of their flaws is the reason that you’re unlikely to relate to any one of them wholeheartedly, or to all of them at once — but almost guaranteed to relate to two of them a little. This is why Stevenson’s particular innovation — that everyone is a mixture of characters — is so effective. Nobody takes their real faults to such parodic extremes, but we all contain degrees of at least two major personality flaws.

The presence — indeed, predominance — of “bad” qualities sets this personality test apart — you’ll see no flattering Leo or INTJ profiles here — but even more unusual is the way it highlights the ability to change. Because The Good Place is a show about bad people getting better, relating to a character means not only relating to her flaws but relating to her struggle. That’s not something that’s usually reflected in personality tests, which purport to tell you who you are, not who you’re trying to be. But lots of people struggle to be good, and it’s the struggle that defines them. They don’t necessarily identify with good or evil, but with trying and failing. They understand morality is important, but to actually aim to be moral all the time is daunting at best, paralyzing at worst.

Because The Good Place is a show about bad people getting better, relating to a character means not only relating to her flaws but relating to her struggle.

It’s that struggle — the relatable ways they fail, yes, but also the ways in which they attempt to get better — that makes us identify with the Good Place characters, much more than any other part of their personality. Eleanor’s scheming ways can be traced to a hardscrabble life where the only person she could rely on was herself; Jason’s puppyish dopiness precludes him from thinking too deeply about the foolish things he does; Chidi’s maddening inability to act stems from his staunchly ethical compass; and Tahani’s need for attention and praise comes from a life of never being really looked at with any kind of focus. Meanwhile, Michael’s never had an impetus to be good and think of others, while Janet’s never had feelings that were all her own, and thus want to be — need to be — selfish.

Choosing two characters creates a dialectic between two kinds of flaws, two ways to be a moral failure — but also produces a more nuanced illustration of the way you might struggle and change. For example, if you were actually a Jason/Tahani, you might be driven by a sweetness and kindness that you constantly undercut with badly thought out or straight up frivolous decisions as you choose to cater to those who couldn’t care less, all in the name of a dream that isn’t really well thought out, or may even just be based on how much admiration you’d receive. If that fits you, well, rejoice in it. Because part of playing this game is in recognizing your moral failings, you are also enjoying a kind of self-awareness that escaped the main characters for so long.

In the show, the characters are motivated mainly by the idea that there should be a “Medium Place,” for people who were maybe not great but are trying, in their own way, without the self-awareness to understand the way they’re failing. We all probably belong in the Medium Place, which is why we find the Good Place characters so sympathetic.

Maybe the joy of choosing two characters from such a show is in the vein of the show’s theme: everyone’s a little bad, but what matters is that you try.

Which The Good Place Characters Are You?

You probably already know, because this test is just that good, but if you’re having trouble deciding… well, you’re a Chidi. But just to humor you, here are some signs you might look for to indicate which characters you are.

You may be a bit like Eleanor if you…have a superiority and inferiority complex, where you believe you’re capital-R Right about capital E-everything, and are judgmental, dismissive, and more than a little harsh when it comes to what other people care about — mainly because you’re so dismissive of caring in general.

You may be a bit like Tahani if you…check on Instagram or Facebook or Twitter and obsess over your Like-Retweet-Comment ratio — but are also already popular enough to regularly enjoy huge gatherings with a lot of people you call your friends. These online and offline socializing sessions somehow always end with you crying over someone dismissing you in a very hurtful way…which you then pretend didn’t matter anyway. You solve your problems by appealing to a higher authority (someone’s manager), because no one has really ever listened to you for you.

You may be a bit like Chidi if you…don’t like making big decisions because you see each decision as taking you a whole other parallel life and what if you make the wrong one and mess everything up and you’ll never be happy again? Then again, when the universe presents you with a ready-made decision, you will assume it’s absolutely correct, ignoring any part of it that might seem off to you.

You may be a bit like Jason if you…only skimmed this article. Somehow you end up in situations where everything is in fire (figuratively, hopefully), and you can trace exactly what actions led you to that place. You tend to act before thinking, and then solve your problems by…acting again without thinking. You once solved an argument with a hug, and you use that tactic regularly, despite diminishing returns.

You may be a bit like Michael if you…are the type of person who says they hate drama, but actually love love loves drama. You just know exactly what to say to people to get them to let you invade their friend circles to wreak sweet, sweet havoc. You also find other people fascinating in a sweeter way than you can admit.

You may be a bit like Janet if you…are reading this article maybe because a friend sent it to you and wants to discuss it with you. You are so nice and everyone loves you, but you are always creating higher and higher bars for yourself, so you feel like you’re failing when everything is actually fine. If you have and acknowledge your own feelings, the world will not be destroyed, I promise.