essays

Why We Still Need Richard Hugo’s Defense of Creative Writing Classes

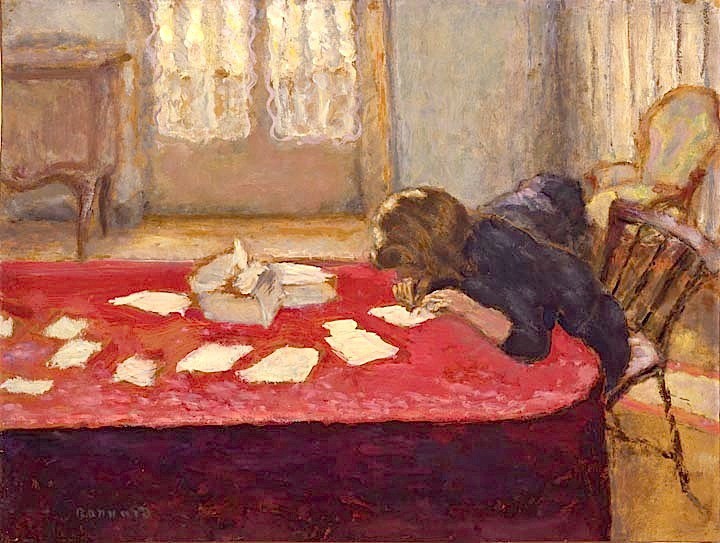

It’s a fact that all arts administrators hide when we are out in the halls amongst the people we serve: every one of us, particularly in nonprofit, eventually and then regularly turns away from the spreadsheet or the emails, lowers her head to the desk, and wonders if anything she’s doing is helping anyone, or the art, at all. In my three-year tenure working on the creative writing programs at Hugo House, during these desultory moments or weeks, I closed my office door and controlled my facial expressions, even among fellow coworkers. No one needed to be further infected with existential crises.

My problem wasn’t helped by the constant debate over whether creative writing classes should exist at all, some even making the unsubstantiated claim that creative writing can’t be taught. Richard Hugo — the Seattle/Western Montana poet Hugo House was named for — might have dismissed an argument over whether creative writing can be taught as “semantic rhubarb.” Defending creative writing classes is a primary concern in his essay collection The Triggering Town. And in dark times, that book kept me administrating, sent me back to the spreadsheet with renewed vigor, or at least less confusion.

In the essay “In Defense of Creative-Writing Classes,” the most underlined section in my copy of The Triggering Town, Hugo immediately establishes the reason why writing education will always exist: “Writing is hard and writers need help…. As long as people write, there will be creative-writing teachers.” He assures us that the new writer could skip the whole “am I/aren’t I?” struggle. “A genuine impulse to write is so deep and volatile it needs no triggering device other than the one it already has…and that remains mysterious, evidently complete in itself.” The impulse is indelible and ineffable. So get writing.

Hugo wrote, “A good creative-writing teacher can save a good writer a lot of time.” For students, he lays out knowledge that will save a fledgling writer some pain. I’ve been lucky to have a few of those teachers that saved me a lot of time.

What to write about? “Most young writers haven’t learned to submit to their obsessions,” Hugo tells us. A writer can skip some of the pain of becoming by going at those weird, individual preoccupations we all carry around. One teacher helped me submit earlier and sooner to my obsessions by pointing out a misdirected choice of subject. I was writing about mid-twenties creative types stumbling around New York City. “You have much more interesting things to write about, I think?” she said. There are a lot of great books written about young New Yorkers; she wasn’t dismissing those books. She understood that I wasn’t very interested in what I was writing about. “I’m waiting on those other stories until I’m a better writer,” I said, to my own surprise. “Don’t,” she said.

That same teacher argued that, even if you’re writing badly about the subjects you care about the most, to get any better, you’ve got to write. Or, as Hugo wrote, “You’ve got to stay in shape and practice to do it (writing) well.”

Another shortcut that teacher gave was to read, read, read, exemplified in the dozens of books and stories she referenced each class. Hugo felt the same way. As much as he revered great teachers, he also revered what writers learn by reading. “(In English departments) the enrollment in creative writing increases and the enrollment in literature courses is going down. I’m not sure why and I’m not sure that the trend is healthy.” He wrote that if an English program has to choose between advanced poetry and Shakespeare studies, to choose Shakespeare. But he was not in favor of literary snobbery. He lamented equating superior knowledge with superior social status, and he dismissed willful ignorance in the service of maintaining appearances: “A lot of students today would rather not learn Milton than be made to feel inferior because they didn’t already know his work.”

Hugo was a much, much better person than 19-year-old me. I took Milton exactly because I wanted to feel superior; I craved the feeling because I thought it might help me climb out of where I came from. What shocked me about the class was — and is in retrospect no surprise considering my love of reading and the common occurrence that well-loved literature is loved for good reason — I loved Milton. My third and fourth tattoos are devoted to an idea slowly built across Paradise Lost that man is neither good nor evil, but in limbo between the two. I grew up in a bisected world: Good. Bad. Milton’s expression of the complex motivations within humanity made me hate everything, including myself, a bit less, as well as feel deeply frightened and unsure. What else is literature for?

For teachers, Hugo demands no less complexity than Milton’s concept of both good and evil contained in one animal. Hugo believed that a writer cannot teach anyone how to write. Instead, much like Keats’ negative capability, “We teach how not to write and we teach writers to teach themselves how not to write. When we teach how to write, the student had best be on guard.” One thing I love about this is it demands that a student bring a certain amount of skepticism into the creative writing class, as well as asserting of the mystery of what makes good writing.

Perhaps most importantly, Hugo roundly dismisses any teacher who would deny access to or effort toward a student. Hugo came from a working class background in a working class area of Seattle, and I believe his experience helped him understand the importance of even a bit of success and beauty in life:

“What about the student who is not good? Who will never write much? It is possible for a good teacher to get from that student one poem or one story that far exceeds whatever hopes the student had. It may be of no importance to the world of high culture, but it may be very important to the student. It is a small thing, but it is also small and wrong to forget or ignore lives that can use a single microscopic moment of personal triumph.”

And I have barely begun to mine the gems in The Triggering Town. Two of my favorite pieces of advice in the book, applicable to both students and teachers (and when does a teacher stop being a student?) come from the book’s first essay, “Writing Off the Subject.” “In real life, try to be nice. It will save you a hell of a lot of trouble and give you more time to write,” and, “As Bill Kittredge, my colleague who teaches fiction writing, has pointed out: if you are not risking sentimentality, you are not close to your inner self.” It’s the kind of book you read over and over, if only to believe again in what you’re doing. I’d guess Hugo wrote it not only for all of the ambivalent administrators of the world, but also to get himself straight on matters.

Hugo believed in creative writing classes, and he believed in behaving humanely, even if stories suggest he might have been a little tough. Hugo House could not ask for a better dead mentor, channeled through The Triggering Town. What else do we need to know: creative writing classes and mentors will always be needed; listen to your colleagues; read and write; don’t hide your ignorance; follow your obsessions (or as we might say now, nerd out); try to be kind, if only because it will get your further; don’t pretend to know the answers; and if it’s in your power to give it to them, never deny anyone the experience of writing that one beautiful line.