Lit Mags

Wintering Over

by Jason Brown, recommended by The Southern Review

EDITOR’S NOTE By Cara Blue Adams

Jason Brown is a master of the short story, and “Wintering Over” is Brown at his finest. What immediately hooked me is the story’s honesty and emotional resonance. The subtle humor, too. Brown’s wry sensibility and dark wit are on display as he shepherds his characters through a dynamite plot. I read the story from start to finish in my office on Lakeshore Drive the same hour it landed on my desk, noise and distractions of the day be damned, and immediately wanted to begin it again. That’s what The Southern Review has published since its inception in 1935: stories that are both timely and timeless, stories that compel a reader to turn the pages quickly and to return later to see what they might yield beyond that initial pleasure.

A forty-eight-year-old writer walks out on a book contract and retreats to a remote mill town in Maine to winter over with his young wife, a potter. Nathan and Charlotte are initially excited to escape from ordinary life and regard the winter as an adventure. But things are not going well between them and the isolation does not help. Nor does facing the demands of their art. And the end — well, the end. It’s a knockout. The story builds to a shattering revelation. It’s the kind of revelation that leaves the characters’ lives irrevocably changed, and that changes us, the people who bear witness.

Brown has been widely acclaimed. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Harper’s, TriQuarterly, and other top magazines, and has been anthologized in Best American Short Stories. Author Bret Anthony Johnston says, “Brown’s voice and vision are fiercely original and wickedly satisfying, like a reader’s answered prayer.”

I agree. These stories are lifesavers. To crib from William Carlos Williams, who wrote, “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there,” Brown looks closely at the world, sees its comedy and its failures, and brings us the news — on-the-ground reportage of the human condition.

Winter over with these characters and you’ll see: you will be changed. You will not forget. Nathan and Charlotte will walk around in your mind as they do in the story: crazy and sane in the way we humans are, barefoot in the cold Maine snow.

Cara Blue Adams

Former Co-Editor of The Southern Review

Wintering Over

Jason Brown

Share article

They were going to Maine because Nathan had recently walked out on a book contract and returned the modest advance after declaring that he had nothing left to say. His editor and longtime friend had seen part of the new manuscript and had told Nathan that he had betrayed his own vision (and integrity), a statement that Nathan felt betrayed their friendship. He began to talk of how New York had betrayed itself since the heyday of Greenwich Village (before he was born) and how even Westchester had betrayed itself since the time of Cheever. “I mean, it was awful back then, I’m sure, to be among those people who cared so much about propriety, but at least it was what it was.” He said he needed to make some changes, get back to the foundation. They had decided, he reminded her, to wait a few more years before having children (though she wasn’t sure now she even wanted children), so he could more firmly establish his career. They had time for an adventure.

When he first mentioned spending the winter in Maine, Charlotte had been excited, picturing the rough coast, fir trees, mountains, and clear rivers of the northern landscape she had seen in the Travel section of The New York Times and read about in scenes from Nathan’s own fiction, mined from his boyhood trips to summer camp. She had hoped the beauty would inspire her own work in new directions and had planned to bring her potter’s wheel. She was feeling optimistic, so it was a disappointment to hear Nathan say that he was no longer interested in beauty — this, apparently, was one of the many changes he was making in response to the failure of his last project, which had ended not so much with his walking out on a contract as with his book walking out on him.

“Beauty like that is dangerous,” he said when she suggested they consider one of the places she had heard about, Bar Harbor or Boothbay, with grand old houses and sweeping views. “It’s made me complacent, aesthetically lazy.”

Having grown up on military bases around the country and lived until she was eighteen in the squat, drab houses Nathan had once described in a story as “toad-like,” Charlotte felt she would never be surrounded by enough beauty.

In addition to being too beautiful, Nathan felt that the coast and the ski slopes would be filled, even in winter, with what he called yachthoos and day-trippers, not to mention refugees from the saccharine beaches of the Vineyard and the Hamptons. In fact, he was pretty sure he never wanted to see another beach or ski hill for the rest of his life. That much he knew, he said, and that wasn’t much, he added, which was the trouble, and the real reason for the trip: he didn’t know who he was anymore, as a writer, and therefore as a person.

“I’m not sure this town Vaughn is a nice place — in fact, I am pretty sure it isn’t — but that’s the point, you see? It’s an old defunct mill town — also an ice and granite town — that hasn’t seen prosperity since they made shoes for Union soldiers in the Civil War. But it has an incredible history. I’ve been reading about it. In the seventeen hundreds it was one of the richest towns in New England. Logs driven down from up north were milled on the banks and loaded on ships along with granite cut out of the hills. In the eighteen hundreds they cut up the actual river with huge saw blades and shipped the ice to Calcutta and China. Benedict Arnold camped there on his way to attack Quebec. It does have old houses, and it is an old town, it just isn’t a tourist destination.” He finished the sentence with one of his thin-lipped sneers.

Okay, she agreed. She didn’t need a tourist destination, though she did want to point out that sometimes places were destinations because they were nice places to visit.

“Fine,” she said. “We’ll go to a real town.”

“Are you sure it’s fine?” He looked at her pleadingly, and she kissed him on the head.

“I just want you to start working again,” she said, offering one true statement.

Charlotte had hoped to arrive in Maine before the leaves had fallen, but she and Nathan didn’t descend into the Kennebec Valley until late fall, long after the trees this far north had shed their colors. As they followed the river inland from the sea, they passed, every five to ten miles, a small collection of soporific storefronts and old three-story brick and clapboard captain’s houses built when the country was just beginning. As they entered the town, Vaughn, Charlotte felt relieved by signs of civilization: several antique shops on Water Street, two small country stores, and a restaurant. The houses were in fact beautiful, if scraggly, and there was the river.

The real-estate agent arranged through Nathan’s friend met them at a fantastic colonial with marble fireplaces in every room. Charlotte could set up her wheel in any of these rooms. She ran her fingers over the ripple of a leaded glass window and turned to watch Nathan step into the next room, rubbing the layers of his recently cut hair above the nape of his neck. From the back and except for his gray hair, she could imagine what he must have looked like when he was a college senior. His jaw was as smooth and narrow as in the photos of his years on the college newspaper, though his skin, like his hair, had grayed early, lending a certain gravity to a man who would otherwise remain a boy. In the eight years she had been with Nathan, she had noticed her body aging: the lines around her eyes and mouth, a slight settling around her hips. It seemed now as if Nathan might stay just as he was forever, out of stubbornness, allowing her to catch up and pass him by.

She asked the realtor how much the house rented for and was surprised to hear it was a fraction of what a one-bedroom would cost in their neighborhood in Hastings.

Nathan stopped in the hallway and seemed unsure of where to go next.

“God, there are a lot of rooms in this house,” he said.

“So you two are going to winter over?” the realtor said in his Maine accent, and Charlotte found herself involuntarily shaking her head. Nathan tended to absorb regional expressions, and, whether on purpose or without realizing it, mimic them.

“Yes, yes, we’ll be wintering over,” Nathan answered with a smile.

They visited two other houses that were just as wonderful, though not in as pristine condition. The fourth house they saw was twenty feet from the railroad tracks and across the street from an abandoned warehouse and a Methodist church. The backyard was overgrown with raspberry and strawberry bushes, reaching through wild grass to what had been a vegetable garden. This house was sparsely furnished and heated by a wood-burning furnace, in addition to a wood stove in the kitchen and a Franklin stove in the parlor. In what must have been the dining room, the floor sloped, and at a point where one of the foot-wide pine floorboards had split, Charlotte could see into and smell the dark basement.

“The house was used in the Underground Railroad,” the real-estate agent said. “In the basement you can see where there was a tunnel that used to lead from here down to the factory.”

“Can we see that?” Nathan asked eagerly.

The man had to go to his trunk for a flashlight.

Nathan was already doing what she had asked him not to do: dropping the r’s, lengthening the a’s, and generally picking up the local accent. He claimed it was something writers did, but it embarrassed her, reminding her of when she and her family first moved to a new town and kids teased her until she could rid herself of her old accent. Down in the basement, the agent swept the light over an arch in the wall that had been filled with cinder blocks.

“The train jumped its tracks in 1890, collapsing the tunnel.”

The agent swung the light over to the wood-burning furnace, which reminded Charlotte of something she had seen on a tour of a naval destroyer in San Francisco.

“How many cords of wood does it burn in the winter?” Nathan asked.

“Fifteen or so. Depending on the winter.”

Charlotte climbed the stairs to wait for him in the kitchen. It frustrated her that he could be happy here when they could easily afford one of the stately, more comfortable houses in town. As she tried to picture Nathan rising at five in the morning to descend those basement stairs to feed the furnace, she studied the cracked yellow linoleum that curled at the edge of the kitchen and seemed attached to the floor by little more than its own saturated weight. She often thought of the torture he put himself through for his writing as picking at a scab. In fact, she had once wanted to be a writer herself, and had read about and listened to gossip about writers with a level of eagerness that could only be sustained by not knowing any.

The truth was that she had known about Nathan from his books before she had seen him, and when she first saw him, it was from a distance. She had no regrets about this now. It was the same with anything you ever thought of as beautiful, or anything about which you could be nostalgic. Nathan had been criticized for being nostalgic in his work, but she had always loved the nostalgia in him, in his ability to find certain ordinary things (hammers or saws in junk shops; farmland) not just beautiful but fascinating because he had known them in his boyhood. She wasn’t ashamed that she had once imagined meeting the man she would marry by first seeing him from across a room as she had that summer evening in Saratoga Springs when Nathan gave a reading. She would always see him in this way, which was not so much a romantic fantasy as a part of what everyone called love. She was sure Nathan felt the same way, even if he didn’t understand it in exactly the same terms.

That Nathan had recently identified any kind of boyishness, idealism and sentimentality, nostalgia, or beauty as characteristics he would have to do without when he remade himself in this town, a place that seemed to have been forgotten even by the people who still lived there, did not worry her too much. Nathan was prone to sudden enthusiasms and sudden lows — neither too extreme — and he would always more or less return to where he had started from if she waited and was patient. He liked to talk about the transformation of their relationship, his transformation as a writer and a person, and particularly the transformation of his characters, but as far as she could tell, their relationship, Nathan himself, and his characters were basically the same now as they had been eight years before.

Of course he wanted to take this last house, the run-down one, and she was in no mood to deny him his transformation. She made sure the arrangement was month-to-month, and as he talked with the realtor about the rent and the delivery of firewood (he kept using the phrase, “Do you know a good man?” when asking about carpenters and mechanics), she decided to take a walk up the street.

Charlotte was having a feeling that she had often experienced when she was young and she and her parents arrived in a new place. She had gone from dreading those moves to anticipating them, in no small part, she knew, because her skinny frame had filled out and her round face had thinned. Her skin pricked under the gaze of a whole lunchroom or classroom drawn in her wake. She knew how to hold herself apart, eating alone with her chin held high and waiting for them to come to her, just as Nathan, not that many years later, eventually crossed the room after the rest of the audience had gone home. He wanted to know if she had enjoyed the reading. She listened to his eyes, watched his lips. That night he asked her dozens of questions, but he never asked her who she had come to the reading with. In fact, she had gone to meet a boy she had been dating who didn’t show up, a fan of Nathan’s who had been raving for weeks about his writing. This boy wanted to be a writer, presumably one like Nathan. Now the boy was a lawyer, and she was with the writer he’d wanted to become.

Charlotte thought she knew what Nathan’s real problem was: he was forty-eight years old and no one read his books. Not literally no one, of course, but virtually no one. Aside from grants and fellowships that he seemed to almost resent, he had never made real money from his work, and even though he sometimes took teaching jobs, he had always disdained teaching as an undignified way for writers to earn a living. Nathan was respected, he was reviewed, he went to Yaddo, he gave readings at universities where his friends taught, but he had, she suspected, come to the conclusion (either consciously or unconsciously) that his life’s pursuit was a little bit empty. This was not a bad thing in her mind. Did barbers, dentists, lawyers, realtors, accountants, and carpenters feel that their life’s pursuits were somehow grand or vital? No. Why should Nathan be an exception? She didn’t want him to get depressed, but she wouldn’t mind if he gained a little perspective. So what if he realized he was a cliché? So was everyone. She was a cliché. No need to dwell on it, no need to deny. It was a decent starting point. A bit of honesty. Only he was going to have to come to this conclusion on his own.

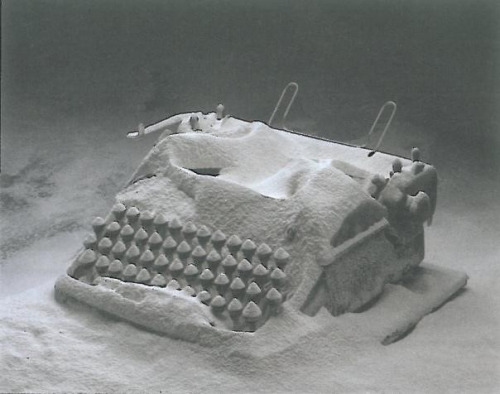

It snowed for the first time two and a half weeks after they moved in. Nathan went downstairs to feed the furnace as he did every morning at five thirty so she could have a hot bath (no shower in this bathroom, only the cast-iron tub). By the time she heard him coming back up, the road sloping down to Water Street was covered in a clear white blanket. She walked outside in her bare feet while the bath filled. The snow didn’t even seem cold melting under her soles. She left black prints over the pavement as she walked down the road, stopping just beyond the tracks and turning to see him in the window of the second floor, watching her from his writing room with a smile on his face. She had the familiar feeling that in his eyes she was a character who had the right appearance for tragic resonance. She gave him the finger, but even this seemed scripted; he laughed and ducked back into the shadow of the room where he’d set up his typewriter, which was tapping away when she came back inside.

Her feet ached in the hot water of the tub. She didn’t linger, but dried off, dressed in the cold bedroom, and headed downstairs with a sense of vigor to her workroom, her “studio,” in what had been the dining room. She started the electric wheel, listened to the whir of the engine, and watched the grooves of the metal disk spin. For some reason, she was hesitant to get started, but finally she dug her hands into the bag of wet clay. Outside, the snow fell pleasantly though the gray air. Her fingers slid down through the clay and squeezed what felt like a knotted muscle she was meant to disentangle into a bowl. The sun broke through the low-lying clouds over the river, and she was just starting to fall into a rhythm when she heard a thundering crash from the back of the house. At first she thought the train had ground to a halt in the middle of town, as it had the other day for some reason, but the noise had come from the opposite direction, and when she looked out the back window she saw an enormous dump truck pulling away from a pile of unsplit wood covering the car lot. The pile stood at least nine feet tall. She hadn’t quite recovered from this shock when the back of an even bigger truck came in around by the old vegetable garden and left what seemed to her enough wood to build a fort. Nathan walked outside and stood between the piles with his hands on his narrow hips.

After handing one of the men a check, Nathan tried to slap him on the back as he looked at the woodpile, but the man had already turned to his truck and Nathan’s hand swept through the air. The trucks rumbled up the hill, leaving Nathan standing there in his flannel shirt, the tops of his bare hands turning purple. She thought about bringing his hat and jacket out to him but remembered that he had proposed that they not speak to each other before one o’clock, before each had done their significant work of the day. Then they would have a full lunch. She could eat whatever she wanted but he was going to fast until one — not to lose weight but to sharpen his edge, he said.

He vanished from sight into the attached barn and reappeared carrying an enormous maul, a tool Charlotte knew well from when her father used to split wood at their cabin up in Minnesota. Nathan set one of the twenty-inch logs on end, stood back, swung the ax over his head, and slammed it into the grain, where it stuck, of course, and resisted his attempts to free it.

Watching was too much to bear; she supposed he would eventually figure out he needed a wedge, and that splitting thirteen cords of wood might take him the rest of his life. She removed her first attempt at a bowl from the wheel and threw on another clump of clay. It was a good throw, near the center, and she pressed her hands together, forcing the clay into shape.

Nathan rose at dawn every day and went to work on the woodpile instead of hammering away at his old typewriter. Often she didn’t know he had left the bed until she woke to the thud of the maul against an iron wedge. He had also decided to chop in nothing but a long-sleeve underwear shirt and blue jeans. From her workroom she could hear a lot of grunting and cursing. He would be lucky, she thought, if he didn’t swing the axhead into his own shin.

One day at lunch he asked if she had noticed the kids waiting for the bus down the street. They stood with their hands in their pockets, wearing nothing but t-shirts as steam poured out of their mouths. “It’s ten degrees outside, and they’re not just pretending not to be cold, they’re not cold,” he said. He put down his sandwich and immediately set out to acclimatize himself by walking to Dawson’s Variety in nothing but a v-neck t-shirt. She was perversely happy when he turned around after ten minutes and immediately plunged himself into a hot bath.

After another week of throwing failed pots and listening to the maul strike the wedge unevenly (in one out of four swings, she heard him hit dead-on), she packed up her clay and the stack of unsatisfying prototypes and pushed it all into a closet. She had purposely avoided the firewood, but now she went out through the attached barn to the largest of the woodpiles. Nathan was somewhere else; just as well because it was before one o’clock. He had managed, she calculated, to split maybe half a cord, though she supposed he might have fed some of what he’d split into the fire already, supplementing the cord and a half that the previous tenants had left in the basement. She picked up the maul by the neck, tapped a wedge into a split in the grain of one of the big logs, and swung down, hitting the wedge squarely in the middle. You couldn’t split cordwood this size with one wedge, and you had to slice at the outer rings before going for the crack in the center. Apparently, Nathan had discovered the same thing, because she found two additional wedges to the left of the pile. One with a flattened splitting edge had been used to pound against another wedge that was probably jammed deep inside the center of one of these behemoths. She backed up, swung again, and split off the edge of the log. Now she could work her way around, making use of the cracks that fanned out from the core. It was good dry oak that would burn hot. When she had split the whole log, she looked up and tasted sweat. Her breath steamed in front of her face, and there was Nathan standing in the kitchen window with a cup of coffee just lowered from his lips. He smiled, though not quite with the same satisfaction as when he had seen her outside in bare feet weeks before. She called out to him, asking if there was any more coffee in the pot. At first she thought he hadn’t heard, but then he raised a finger in front of his lips. No speaking before one.

At lunch he offered her information from his latest reading, a book about the Kennebec by someone named Coffin.

“The Kennebec River is one hundred and fifty miles long,” he said.

“I didn’t know that,” she replied.

“Raleigh Gilbert and George Popham were here from 1607 to 1608!” he said, and resumed reading.

So the writing was not going well, or not going at all. She hadn’t heard his typewriter in a week. When it wasn’t going at all, his mind sometimes latched onto ideas or interests and chewed on them until he was exhausted. She left the room without his noticing and went into her studio, made a fire in the fireplace, and settled in on the dusty sofa to take a nap.

In the morning, she took her clay out of the closet and tried to form a simple bowl she had sketched in her mind, but each time she built up the sides, she squeezed too tightly and the clay came apart in her fingers. A novice mistake. She turned off the wheel, rested her hands on the remaining clay stuck to the spinning wheel and listened for the clicking sounds of Nathan’s fingers on the keyboard. Nothing. She sat there for what felt like a long time and had just started to wonder if he was even in his room when his chair scraped back. His slippered feet scuffed across the floors into the kitchen to pause, she thought, in front of the refrigerator or the cupboard.

She packed her clay and this time pushed the heavy wheel itself into the corner of the room, lay down on the pine floor in her thick sweater, crossed her arms over her chest like a person laid to rest, and closed her eyes. She imagined she could hear her father swinging the maul against the wedge, though of course it wasn’t her father but Nathan. Her father had always worked at the woodpile in his dark blue sweatshirt with the hood pulled low over his brow, steam pouring out of the opening for his face as if from the mouth of a cave.

Both she and her mother knew that her father had professional secrets — his job had been in military intelligence, training people in deception, and he was often guarded. They also knew — and she couldn’t remember when she first realized this — that he had personal secrets, and allowed only part of himself to be known to them. The private life inside him occasionally flickered in his green eyes.

After her father’s death, Charlotte’s mother claimed she had known about the other women from the very beginning. She’d never found any proof and he had never said anything to her, but she had known, she said, because in the end there were no secrets in a marriage. “Your father made himself into two people, one he hid from us and showed to others, and one he showed just to us,” her mother said to her. “One side did not cancel the other out. But you can’t tell them you see through them, you can’t let on that you know, because it’s all they have.”

Charlotte didn’t believe her mother at first, but evidence did eventually emerge: her father had a child with another woman in Florida. She showed up in Minnesota one day and demanded to know what had happened to the father of her child, as if Charlotte and her mother had hidden him somewhere. The woman, whose name was Maria, was half her mother’s age and had a daughter half Charlotte’s age, and insisted that the four of them sit together for part of an afternoon. Charlotte watched the woman’s eyes move from the pictures of her father on the wall to a painting of an old ship that had been in her father’s family. Maria scrutinized the painting before glancing around at the fake wood furniture and the old couch. They had been able to take so little with them over the years as they moved from place to place.

Nathan knew her father had died when she was young, but he didn’t know the rest of it. If Nathan found out about this part of her life, he would want to know everything — he would want more and more and more until he was convinced that she had made all of herself visible to him. Only then would he relax. Sometimes she thought Nathan loved her as he did one of his books that had been typed, set, and bound — he didn’t want to think there was more to the story — and she loved him not because his work was mysterious, which it was when it was good, but because he was not her father, who had burned painfully under the surface with a mysterious longing she never understood. Nathan longed to burn under the surface, but he didn’t. Nathan was smarter and far more sophisticated than her father had been, but fundamentally he was more baffled than passionate.

There was a yell from outside, followed by a grumble. Presently Nathan limped through the back door and into the kitchen with a blood mark soaking through a gash in his chinos. He had finally nicked his shin. She rushed to the bathroom for a bandage and peroxide. When she came back, he was sitting with his elbows on the table, still shaking his head. She pulled up his pant leg and dabbed the bleeding cut with the paper towel.

When she looked up at his unshaven face, his expression startled her. There were dark circles under his eyes.

“You don’t look so good,” she said.

“I haven’t been sleeping,” he snapped irritably.

Several minutes went by as they both waited for the tension to diffuse.

“You know, I was thinking about you out there,” he said, pursing his lips and nodding his head like a colonel who had just ordered an attack on a hillside stronghold. “I was thinking that if you don’t like it here, we can go, we can go back anytime you want.”

She pressed the disinfectant against his leg again, making him wince. “I would hate to see you quit so early on,” she said. “We haven’t even been here that long.” She didn’t know what on earth she was doing. Her heart had jumped at the idea of leaving this place.

“I know, I know, you’re right. Something might come out of me yet, but I think I’m through for good.”

“That’s what you always say.”

“No, I don’t — do I? Well, I know you’re right, but it doesn’t feel…I can’t get rid of this feeling,” he said, and studied her while she pretended not to see him looking and stretched the bandage across his wound.

The next morning, Nathan was out chopping again, and though it was cold he soon worked up enough of a sweat to strip down to his undershirt. Her breath caught at the sight of the wings of his shoulder blades and the knobs of his collarbone. She thought of her father standing in front of the lake in Minnesota on one of their summer visits, spreading his arms like wings and diving into the water as the morning sun sifting though the maple leaves sparked off the ripples.

Ever since she was a few years old, she and her mother had gone to the lake every summer for a month. If her father wasn’t working, he came with them. Rolling hills abutted the lake, and in one place a cliff rose forty feet above the water. Nearby was a village where she met a boy the summer she turned sixteen. The boy was the son of the man who ran the village store. He was tall and narrow with pale skin and freckles. His name was David Munro, and she pictured his face, his long, pale arms paddling the canoe, the tight brown curls of his hair and the way his smile would just appear, like a starling landing on the feeder outside their cabin. David himself was as nervous as a bird and often stuttered in front of her mother, but never when he was just with her. When they first started spending time together and he asked about her father, she told him she didn’t have a father, that she had never met her father, and just as she hoped, he never brought it up again.

David didn’t have a car, so on Sundays, when he didn’t have to work, he walked all the way around the lake, six miles, to see her, and they made their way through the woods to the cliff. She was careful now to remember the details: the sunlight through the maples, the sound of their feet on the soft forest floor. He brought two bottles of soda and cookies taken from the store and she brought an old blanket. What she remembered most clearly was how the coolness of the air in the shade of the forest made her anticipate both the warmth of the sun on her skin when they reached the clearing at the edge of the cliff, and the touch of his long fingers on her naked hip. This was where they went every Sunday, this was their spot, on a soft grassy slope high above the lake. She spread the blanket while he used his jackknife to open the bottles of soda and laid out the cookies on a piece of wax paper. They took off their clothes — they couldn’t wait — and then later, with the sweat drying on their skin, they drank the sodas and went swimming. Usually, they climbed down the trail to the left of the cliff, but the last time they were together before she went back home with her mother, David Munro walked up to the edge of the cliff, stood there until she joined him, and then he dove straight down forty feet into water so clear she could see all the way to the bottom. His long, pale body knifed under, curved through the water, and rose gently to the surface.

She regretted not taking Nathan up on his offer for them to go home. If she brought it up now he would make her responsible for the idea.

Nathan stopped sleeping in their bedroom, and she heard him pacing downstairs at night. He chopped wood every morning and then left the house and came back in the afternoons with armfuls of books from the library, which he took to his room. One of the books, she saw, was a biography of Arnold.

At lunch every day he told her about Arnold, who, according to Coffin, had started off with eleven hundred men and marched three hundred and fifty miles through the middle of the state in November, upriver, with hardly any food and bad maps.

“‘They came up the river in bateaux,’” he read out loud. “It’s ridiculous, Charlotte, what happened here — these terrible boats made of green pine. They didn’t get very far north of Augusta before the boats just started to come apart. It rained, sleeted, snowed, their supplies spoiled, half his men either died or deserted, taking most of the food with them. When the river narrowed, they had to drag what was left of their boats against the current through the freezing water, and when they reached the headwaters, they pushed up the side of the mountains through the spruce and pine woods, which were as thick as wire mesh, until their clothes were shredded. They ate bark to survive and dressed in animal skins. When the remainder of his force did reach the Saint Lawrence, there were only six hundred of them and they couldn’t attack because of sheeting rain — it turned their camp into a pool of mud. More of his troops deserted, more died of small pox. What were they thinking, what drove them on?” Pointing out the window, Nathan said, “During the worst season of the year, they were dressed the way we would dress for a walk in Central Park.” He looked at her, shaking his head. “And do you realize that some argue it was Arnold’s defeat of Burgoyne — in a battle which he fought on his own initiative after General Gates stripped him of his command — that led to the French joining the war, and yet he was betrayed in every possible way by this country.”

At first he seemed excited to talk about his reading, but as the week dragged on he grew quieter, and on two occasions during their one p.m. lunches didn’t even answer her questions about his morning. At night he read by the fire and went to bed in his study without saying a word to her.

By the end of the month they had gone ten straight days without seeing the sun. When it finally erupted one morning through a break in the clouds, even the ground seemed to squint under the light. She moved her stool closer to the window of her studio and closed her eyes, feeling the light and warmth on her face. Nathan didn’t appear in the kitchen at one. She waited fifteen minutes and went to stand by his door. She wasn’t supposed to knock when he was in his writing room, no matter what the hour, but she did. He didn’t answer. She forced herself to open the door. Nathan sat at his desk with his head in his hands. When he didn’t move or speak, she called out his name softly.

“I have been a good husband,” he said finally.

“Yes?” she said, confused.

“Why don’t you just go back to Hastings if it’s so hard for you to be here?” he asked.

“What are you talking about? I want to be here.” This was a lie, of course, but he couldn’t know that.

“I know what you were up to back there,” he said quietly. “It must be very hard for you to be away from him.”

“What are you talking about?” she said again. She felt her stomach sink, as if she had been caught in a crime, though she couldn’t fathom what she was guilty of.

“I should have known this would happen. I won’t say I was waiting for it, but I guess I should have been. I mean, look at me. Can you at least look at me?”

She did, reluctantly, afraid he would be different somehow, but he was the same, only with deeper circles under his eyes. He had lost weight. She started to speak, though she didn’t know what would come out. He waved her off. He obviously assumed she was offering an excuse.

“I don’t understand how you can stand in front of me as if nothing has happened. I see now I must have sensed it, probably the first day you were with him. No wonder you were reluctant to come up here.”

“But I was happy to come here. And what do you mean ‘him’?”

“It must be hard being separated from him,” he said calmly.

“Who? Who?” she said, her voice hysterical in her own ears. She was trying to sound rational but it wasn’t coming out that way. She wondered who he could be thinking about. His friends Jerry and Michael? Most of her friends were women, except for Henry, who weighed over two hundred and fifty pounds.

“Yes, who,” he said calmly, looking at the floor. “Who are we talking about?”

There seemed no point in trying to defend herself when there was nothing to defend. She took a deep breath and tried to remember that he sometimes worked himself up over small things when his writing wasn’t going well, though it had never been this bad before.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Why would I know? You tell me.” He gazed around his writing room. “But please,” he said, closing his eyes and shaking his head. “It’s hard enough for me in here without the details.”

“What details?” she said.

With a final, defeated shake of his head, he got up, walked past her, and quietly closed the door.

She pulled on her jacket with shaking hands and went out to the driveway, where she immediately felt the bite of the air on her cheeks. There was no defense against this cold except to hurry down to the store where the two women standing at the counter stopped talking and leaned forward over the cookstove that burned all day long. She envied them terribly for each other’s company. Surely, they knew each other in a way Charlotte would never know anyone. They comforted each other, they had no secrets. She couldn’t imagine what they thought of her.

“Is there anything we can help you with, dear?” the woman behind the counter asked, but Charlotte just stood there with her mouth open, staring at the woman’s face, which was soft on the surface, where her skin sagged into jowls, and hard underneath, her small unwavering blue eyes seeming already to have judged her.

“It’s so nice and warm in here. I was just walking,” Charlotte said finally.

“Where were you walking to?” the woman said.

Charlotte turned around and pointed in the direction of their house, realized that wasn’t right, and pointed in the opposite direction. “I was just out walking,” she said again.

The woman looked at her friend and back to Charlotte. “If I was you, I wouldn’t be out walking in this weather unless I had somewhere I had to get to,” the woman said. “It’s below zero out there.”

“You’re probably right,” Charlotte said, and then without warning tears streamed down her cheeks and dripped off her chin into her mittens. The woman came out from behind the counter and pushed a stool under her and told her to sit down.

“Now, you’re renting the Davidson house,” the woman said. “You’re with the writer. Have a seat and I’ll get you some coffee. Pour her some coffee, Nancy.”

This Nancy had been staring at Charlotte with narrowed eyes. Now she reluctantly reached around and poured coffee into a Styrofoam cup.

“I’m Helen and this is Nancy. You and the writer came up here from New York to stay the winter.”

“From Hastings,” Nancy said.

“Did Nathan tell you all this?” Charlotte asked.

“The writer? No, he didn’t tell us much about himself. Nancy mentioned to him once that the winter was an odd time of year to come up here if you had your choice.”

“I would go to Florida,” Nancy said.

“And this seemed to please him for some reason, that we thought he was so odd,” Helen said.

“He’s writing about us,” Nancy said.

“Stop it, Nancy.”

“Jack thinks so, too.”

Helen gave Nancy a long look before asking Charlotte if she wanted any cream in her coffee. She didn’t, but she wanted them to keep talking. It felt as if she hadn’t spoken to other people in months. Helen’s hand still rested on Charlotte’s shoulder, and as long as it stayed there, she could keep from crying more.

“We’ve seen you in here and down at Dawson’s and walking around town down by the river, but you don’t know anyone.”

Charlotte wrapped her arms around her stomach and looked out the window and across the street, where the river looked frozen solid between frosted banks, though she was sure a current still flowed under the ice. Her father had talked to her about ice fishing. When he was young in Minnesota, they had drilled a hole in the lake ice with a hand drill and sat out there on milk crates. It was one of the few things she knew about his growing up.

The summer she turned nine her father took her alone up to their lake camp. He had fought with her mother the whole previous year, and that summer was meant to be a trial separation. The night they arrived, he started talking about grace and dignity as they sat in front of the fireplace. You have to make both for yourself, he told her, and there were two kinds of grace: the kind that came to you free and the kind you had to put together from scratch. He had no respect for the former, just as he had no respect for the kind of dignity acquired without great difficulty.

They set out in the canoe in the morning and anchored not far from shore. They both had fishing poles, but he lay in the bottom of the canoe with his hat low over his eyes while she let the line drift without bait. On the third day, he curled up in the bottom of the canoe and did not stir as she sat in the bow listening to the waves lap against the side of the boat. Again, he said nothing all day. She was dizzy and weak and the sky darkened with a cold drizzle. She was afraid to speak to him, to break the silence. His stillness was a threat she didn’t understand. Finally, just before dusk, he sat up from the bottom of the canoe without a word and picked up his paddle. She was too hungry to help, and she just leaned over her knees in the bow as the canoe surged forward with the power of his strokes.

Charlotte stood with a smile for Helen and Nancy and left the store. Walking up the hill toward the house, she tried to think what would happen if she kept going past the old houses and streets and into the wide, snow-covered fields. She couldn’t walk far, not in this cold, and she felt now as she had then, when she was nine with her father, as if she would always be among strangers.

In the kitchen Nathan sat hunched over his dinner and didn’t look up when she shut the door behind her and stood above him. She said his name in a voice calculated to avoid the kind of hysterics he abhorred, especially in other people’s fiction. But he didn’t answer, he had finally stopped talking to her. After a while, he slid back his chair with exaggerated composure and took his plate upstairs.

The next day she removed her wheel and the clay from the closet, wet her hands, and smoothed a lump into the wheel’s center. She wanted to make something completely different than the cups and bowls she had sold to the handful of shops in Hastings. She wanted to make something that had no use at all, not even as a beautiful object, but she knew her ideas on this subject were unformed — without these qualities, utility or beauty, how could an object have value? Utility and beauty — both felt to her false. False how, she didn’t know, but she was sick of making things that people used for their food or things that they would think looked pretty on their kitchen tables. There had to be something more than pleasing people.

She stood in her workroom staring down at her wheel and bag of clay and tried to recall the person who had once been interested in making pots. That person — her for eight years now — was not only gone, it was as if she had never existed. She closed her eyes and listened. She could identify every sound: the noon whistle echoing down the valley from the firehouse, the faint vibration passing into her fingers minutes before the train passed through, and the sound of trucks driving up the street. And Nathan. Finally, she heard the door slam as Nathan returned from his walk.

Now she could begin her own walk. She chose north, setting out with a brisk pace, almost a march. She hadn’t gone more than a mile, leaning her head into the wind that funneled down the river from Quebec, before she realized someone was watching her. She turned around several times to make sure and once even waited behind a tree to see if anyone would appear, but no one did.

It started to snow in light flurries, as it had every afternoon that week, obscuring her view of the river. She was on a march, she realized — the march Arnold took not so much against the English but against the miles standing between him and the English. She stopped short at the Augusta Bridge and watched cars pass through the snow.

Over the next three days, the snow only let up for brief periods before coming down again. Nathan had been avoiding her, only coming out of his room when she went upstairs. Every day when she went out, he watched from the front window, she noticed. Whenever she woke at night, she heard him walking about the house, so he wasn’t sleeping.

On Sunday, she went up to the mute door of Nathan’s room. She could hear the pages of his Benedict Arnold book flutter inside, and she realized that in the many moments of stopping outside his door over the years she had learned to detect his moods from the force of a page ruffling flat or the tempo and rhythm of the barking keys. If only the typewriter would start barking again they could go back to their lives, she allowed herself to think briefly. She knew, though, that there was no going back.

She pounded her fist on the panel so hard she thought at first the whole doorframe might collapse.

“Come out of there!” she yelled. “I can’t just sit out here by myself with no one to talk to!”

He appeared in the doorway. The sight of his oxford tucked into his khakis and his salt-and-pepper hair made her feel disheveled and slightly crazy.

“You have no idea what it feels like, do you? If you did, then you would have never…” he said. He looked oddly calm.

“Nathan, I have no idea what you’re talking about.” She tried to keep control of her voice.

“I can’t think. I can’t work. It’s not the sex part of it that upsets me. It’s that you love him. That’s what I can’t bear.”

“But I’m in love with you,” she said helplessly.

“You saw me from across the room that night at my reading. I was up on stage. You were telling yourself a story, only it wasn’t the story I was reading.”

“What are you talking about?” Her voice had a slight whine to it, like a child’s, and she took a step back.

“I knew you would take everything from me,” he said.

“Take what?” she said, finally raising her voice, realizing too late she was yelling. “What have I taken? You have everything.”

“All I’ve ever wanted was dignity, and I gave it away for you, and now I’ve lost you.”

“But Nathan, I’m right here.”

“You’re not,” he said. “You came up here thinking you could forget him, but you can’t, can you? On your walks, in passing cars, in the window of the barbershop, in Dawson’s or Nason’s station. You know it’s not him when you stare at people but you keep staring.” He shook his head sadly at her and when she didn’t speak, instead stood there trembling, he closed the door.

The next morning she woke up and couldn’t seem to get out of bed. She was hungry but she couldn’t eat; she couldn’t think but she couldn’t stop thinking. She began to run a fever. The heat boiled up through her legs, blushing the pale skin of her belly and face until she broke out in a cold sweat.

The winter light cut like a blade as her skin steamed the air, and she began to sense someone lingering at the edge of her thoughts, drawing her back into sleep, and then he was in the room with her standing over her bed. She couldn’t see his face but could sense that he was familiar. Finally, he drew so close to her that his features were clear in every detail, his thin nose and pale, almost translucent skin. He wasn’t there, but he wasn’t not there. Convinced it was the man Nathan accused her of loving, she rushed downstairs and searched through the kitchen drawers for a pad of paper and a pencil to draw him; but by the time she sat down at the table and leaned forward, her hand shaking from hunger and heat, he had vanished. Her stomach squeezed the air out of her lungs. She loved this other man, just as Nathan had said, and she couldn’t live without the smell of his skin and the touch of his hand, sensations she somehow knew exactly but had never experienced. The tip of the pencil rested on the lined paper, leaving nothing but a small gray dot; the image of the man’s face had already faded in her memory. She couldn’t hear his voice but she knew the feeling it gave her, and she knew its absence was more than she could bear. Somehow she managed to climb back into bed, too exhausted to cry but wanting to sob with frustration and despair.

By evening her fever had started to break, and the man reappeared, this time off in the distance in her thoughts, walking down a street away from her. He wasn’t walking fast, but somehow she still couldn’t catch up. When she finally saw him one last time, just before dawn, he was sitting on the other side of the frozen river, looking across at her, three hundred yards of ice between them.

The understanding that he was gone for good came to her with a wave of nausea. The blue ink of this inexplicable loss spread through her thoughts. After hours of lying still in the dark, the sun rose above the hill on the opposite side of the valley, filling her room with a sheer white light. Another day. How long had she been in bed? She fell back asleep and woke sometime in the afternoon. Starving, she went down to the kitchen, poured a glass of milk, and drank it in gulps until her stomach unclenched and she was hungry for more. She cracked six eggs and dropped them in the iron skillet with a hunk of cheddar. Stuffing one piece of bread in her mouth with a slice of butter, she cut up the rest and tossed the slices on the grate in the oven. The heat from the stove flushed her face as the pepper, crackling with the eggs, stung her nose. She ate everything and was still hungry.

Nathan came into the kitchen and she tried not to notice his ashen cheeks, his bony shoulders under his frayed button-down. He sat down opposite her at the table and rested his forehead in his palm. The low winter sun moved to the west, submerging the kitchen in a heavy gloom.

And then he reached out and took her hand. He squeezed so hard the knuckles of her fingers pinched together.

“I am sorry. I am so sorry. I don’t know what’s been wrong with me. Can you forgive me?” he said, his voice faltering. He sounded like a boy. “I don’t know what came over me.”

She didn’t know what to say and for several moments she couldn’t speak. She laid her hand over his and thought, at first, of telling him that he need not worry, that his writing was not going well and she understood that he had lost perspective. But the room, the house, and the town were dark around her, and there was only one way forward: through his pleading blue eyes.

“There are things I haven’t told you,” she said finally, and she was as surprised by what she said as he must have been: his eyes widened and she felt his hand begin to pull away. She was desperate, suddenly, to hold his attention, and she pulled him closer. “When I was young,” she said, “nine, my father and I went up to a cabin on a lake in Minnesota, where he grew up.” She described to him the size of the lake and the color of the sky in the summer, the pine smell of their cabin, the old metal Grumman canoe they pulled up on the beach. She told him about the village on the opposite side of the lake, smaller than Vaughn, a ghost town except in the summer.

“Where was your mother?” Nathan asked, his brow furrowing.

“It was just the two of us,” she said, knowing she had to move forward, to say what she was going to say: “and it rained most of the month.” Nathan leaned in closer. “We were there for five weeks that summer, five long weeks in the rain with nothing to do.” She told Nathan about going out in the canoe with him to fish and how her father would just lay there in the bottom of the boat, and how back in the cabin there was little food. And he wouldn’t speak; he sat at the table, fed the wood stove, and drank Scotch. How he left her for days at a time alone.

“I want you to know this,” she said. “He wasn’t violent.” And it was true, he had never raised his voice, not once that she could remember. “But I was afraid of him,” she said, and this was true as well. “Afraid,” she said, “of his stillness. And then one night,” she continued, not knowing what she would say next but looking Nathan right in the eyes, “he waited for me to go to bed and he took out his revolver.” Nathan’s face was so close to hers she felt his breath on her lashes.

“After I turned out the light in my bedroom he put the barrel in his mouth and held it there. I don’t know how long. I waited for it to go off, but it didn’t, and finally he took the gun out of his mouth. He did the same thing the next night,” she said, “and the next night, and the next.”

She held her quaking voice steady by tightening her grip on Nathan’s hand, and she had the distinct sense as her thoughts moved forward that she was relating a story she had heard from someone else, a story that could only be made up. “Every night that week he held the gun in his mouth, and you have to understand,” she said, her voice rising as she lifted her chin into the air, “that I was afraid of what he would do.” Nathan nodded quickly, impatiently, afraid, it seemed, that she wouldn’t go on. “One night after he fell asleep in the chair I walked into the living room, picked the gun off the table,” she said, “and I shot him in the face.”

Nathan’s eyes froze, unblinking. The vein in his temple pounded and she watched impassively as tears filled his eyes and he drew her to him, wrapping his arms around her and stroking the back of her head, presumably to comfort her. She felt nothing at all, though. She was empty except for her desire to finish the story. She let him comfort her, kiss her neck and wipe his tears, and then she finished: after she shot him she did nothing. She set the gun down next to him. She didn’t know how long she stayed there unmoving. She remembered thinking, Now it is finished. The sun came up. The air hung still and heavy over the lake, as humid and fetid that morning as the breath of a dog. There was no one for miles, no close neighbors, and every direction she could think of running led nowhere. She started walking through the woods and then down the dirt road. Her footsteps were accompanied only by the rain pattering through the maples. It was six miles to the village on the other side of the lake, and as she walked down the corridor of pines some part of her kept thinking her father might drive around the corner. Maybe he had been shopping, to buy a new fishing rod, or buy lumber, or food. He would drive up alongside her and push open the passenger door and tell her to hop inside. From the village, she called her mother, who drove over and picked her up. Her mother asked where her father was, and she could only say that he was gone. So her mother drove them downstate to their home and they waited, but her father never came. For months everyone assumed he had simply vanished, until hunters found the body at the cabin. It was possible, until now, that none of this had ever happened because she had never told anyone. It had lingered in the back of her thoughts, like the memory of a childhood nightmare.

Nathan looked away for a moment, shook his head, and looked back at her. He couldn’t believe, he said, that she had kept this from him for all these years. But he did believe her, she could tell from the way his eyes had widened, pupils dilated. He believed her, and that was all that mattered.

The house was cold, and even though she was still hungry and he probably was, too, she took him by the hand and led him up the stairs to the bedroom. She undressed him as he stood in the dark with his arms at his side. He had lost so much weight. She took his flannel pajamas out of the pine chest and helped him dress, first one arm and then the other. She lay him down in the bed and, too tired to find her nightgown in the dark, stripped to her underwear and lay down next to him under the comforter.

“It’s awful,” he whispered. “It’s an awful story.” She put her hand over his lips. Within moments he fell sound asleep, his hand cradled against her chest and his mouth slack against the pillow.

She wondered what she would say to him when they woke to the morning light. He’d have so many questions, so many doubts, and she would have to go over what had happened again and again. She would have to start right from the beginning, reshaping the whole story of her life, telling it and retelling it, until, from exhaustion more than conviction, they both believed it was real.

She propped herself up on one elbow and gazed through the window and down the hill to the dark colonial houses on Second Street. The town was asleep except for the street lamps stationed every half a block like sentries. Without waking, Nathan stirred and grabbed for her hand as if afraid she wouldn’t be there. She was here, though, wide awake, vigilant. The winter moon covered Nathan with silver light, revealing what he would look like in twenty years, an old man, washed of all color like a weathered bone, and she saw, with relief, that he would give up anything for her, even the truth. When they woke in the morning, they would pack the car and head east along the river and then south toward home. He wouldn’t ask her a single question, and she would not have to say another word.