Books & Culture

‘With tears distill’d by moans’: The Bittersweet Hopefulness of ‘Holding the Man’

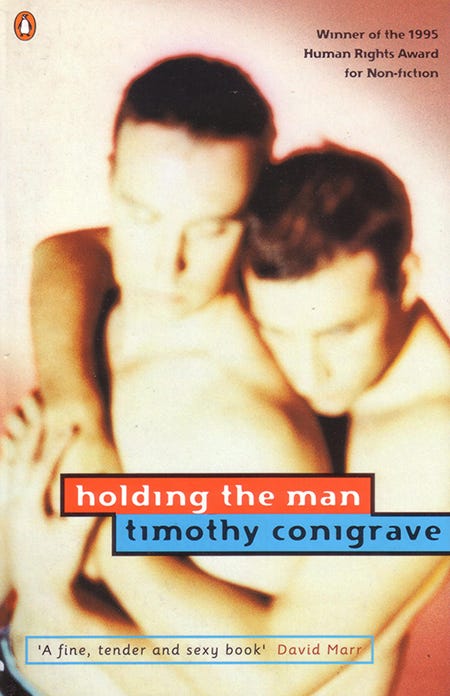

Timothy Conigrave’s memoir of love and grief adapted to film

Timothy Conigrave’s memoir, Holding the Man, was published in his native Australia in 1995. The title of its first section keys you in immediately to what preoccupied a young Tim: “A Head Full of Boys.” Despite growing up at the end of the freely loving sixties (when “the world seemed very exciting for a nine-year-old”), Conigrave was not spared the bullying and badgering that greeted most young boys who happened not to be like the others. As he describes it, he never cared much about sports and would not have been able to define what “holding the man” even meant. What he did know, however, was that he had an unusual interest in other boys. He gives us his thoughts after he’d started up at a new all-boys school:

Sitting nearby was the sunglasses boy. I was thinking about his looks. What makes me think he’s handsome? I like the way he is. Calm and cool. Would the other guys think he was handsome?

Holding the Man’s most touching moments happen when Conigrave finds himself navigating, in ways both intellectual and emotional, his own sexuality. The book is honest in its exploration of the oft-hushed musings of pubescent homosexual boys, as well as in its frank mining of the limits of radical queer sexual politics in the 1970s and 80s. “You know I love you,” he tells his then boyfriend. “But I’m worried that we’re missing out on what people our age are supposed to be experiencing … I don’t believe that it’s fair to expect our lovers to fulfill all our needs.” Page by page we are guided through a personal narrative which overlaps crucially with the conversations happening around gay liberation in the late decades of the twentieth century.

In contrast, the filmed adaptation of Conigrave’s memoir excises these schoolyard moments almost entirely, opting for a framing device that allows for brief flashbacks. The film, directed by Neil Armfield, opens not with a bumbling young Tim negotiating his newfound same-sex attraction (a chastely erotic friendship with his fellow schoolmate, which endearingly ends with a realization: “Fuck, I’m a poofter.”). Rather, we’re given a first glimpse of our protagonist in his thirties, running down an Italian seaside street towards a payphone. When he finally connects with a female friend he is desperate to ask her: where had John been sitting during that first dinner that they had all shared together? He is already starting to forget, and he wants to get all the details right.

The effect of this structural change from the book is twofold: it dispenses with the narrative teleology that memoirs such as Conigrave’s depend on, and in doing so makes the film less about Tim than about the budding romance between him and his eventual partner, John Caleo. While the love story between the two is at the heart of Holding the Man the book, in minimizing Tim’s questioning teenage years the film refuses to simply walk its viewers through a narrativized version of what it’s like for someone to realize and act on their own homosexual urges, engaging the audience in a different way: by expecting more. Similarly, the film, released first in Australia in 2015, refuses a linear narrative for John and Tim’s romance — and later, of John’s death — shuttling strategically between them instead.

This strategy, of flashing back to their shared memories, immediately transforms the material into a narrative about grief. Not about AIDS — which we soon learn precipitated John’s decline — but about the aftereffects of that incredibly immense loss. The short phone call alerts us to the dual facts of John’s passing and of Conigrave’s heartbreak. When Tim runs out of change and must begrudgingly go on without being able to accurately recollect and thereby resurrect John (was his former lover sitting next to or opposite him at the party that night?), his feeling of strandedness overwhelms the screen.

As if in preparation for that moment, in the filmed version we are first introduced to the teenage Tim as he gets ready to perform Paris’s monologue at Juliet’s tomb. Dressed in full Shakespearean garb and awkwardly reciting his lines before his classmates (who snicker when the drama teacher asks him to imagine, by way of inspiration, what it might feel like to lose his girlfriend), Tim eventually finds his bearings. Unknowingly, he delivers the words that distill the loss he’ll come to feel for himself, when the boy he has in mind is gone:

Sweet flower, with flowers thy bridal bed I strew, —

O woe! thy canopy is dust and stones; —

Which with sweet water nightly I will dew,

Or, wanting that, with tears distill’d by moans:

The obsequies that I for thee will keep

Nightly shall be to strew thy grave and weep.

In this nod to Romeo & Juliet both the film and book reveal an aspiration to treat the story as a break and continuance of the long history of star-crossed lovers. But, rather than the expected comparison of Tim and John to the play’s eponymous lovers, their story is instead tied to Paris — to his grief, his tears (and, for readers of the Bard, to his ill-fated death, which follows shortly after this heartfelt scene).

And yet, the very specificity of Holding the Man fights back any attempts to pinkwash its subject matter. This is an unabashedly homosexual film which tackles gay sex (even and especially in tandem with its treatment of AIDS) with welcome revelry. And again, because the film refuses a linearity of narrative, it manages to push back against reductive assertions that promiscuity led to its protagonists’ diagnoses. Not only are we given steamy sex scenes before and after Tim and John learn their HIV status, but the film stages its most heartbreaking moment as a tender lovemaking scene late in John’s struggle with his illness. Walking into his own childhood room, where years earlier John had asked Tim to screw him (“I want you inside me,” he pled), the scene functions as a meaningful re-performance of their youthful sexual bliss.

Sporting a shaved head and carrying around an oxygen tank John sits on his bed, yet again asking Tim, “Will you screw me?” He may be frail, and the ensuing lovemaking awkward, but its depiction regardless speaks to the film’s staunch refusal to vilify consensual sex between men in the age of AIDS, while also celebrating the strong bond these two boys, whom we’ve seen grow up together, have with one another.

To top it off, the scene features a song written especially for the film, which restates that grief is the central narrative engine here. Composed by out singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright, “Forever and a Year” is a melancholy ode to a lost loved one, even echoing Paris’s monologue:

A drop of rain, I swear

I felt upon my forehead

Why is it now

I cannot wipe my brow

’Twas not a drop of rain

And now your hands, I am holdin’

It was a tear

Forever and a year

Rather than using the track as a form of emotional underscoring after we’ve witnessed the loss, or presenting it diegetically with an onscreen depiction of tears, Armfield instead deploys the song for what turns out to be the last moment of sexual intimacy between Tim and John. It’s a powerful moment for the way it re-centers sex as integral to their relationship. At once caregiver and sexual partner, we see Tim holding John in his arms, cradling his frail boyfriend while fucking him, appropriating the sports expression that gives Conigrave’s memoir its title.

Armfield confronts us with a radical image that brings together the two inescapable tropes of the AIDS film — sex and death — marrying them in a heartwarming and heartbreaking tableau. By the time Wainwright croons, “There’s only bright skies about us, just look away, just turn the other way,” the audience has been invited not to ignore the impending grief, but to embrace instead its palliative force. The bittersweet hopefulness of Holding the Man does not depend on a disavowal of the pain and suffering of men like Tim and John; nor does it presume to tie their story to an unwavering arc of progress. Instead, it focuses on the timeliness and timelessness of their love, their lust, and above all, their grief.

‘Holding the Man’ is currently streaming on Netflix.