Interviews

Woman Is Not Born, Woman Is Made

Sue Rainsford on subverting the gendered tropes of women's sex, illness, and healing

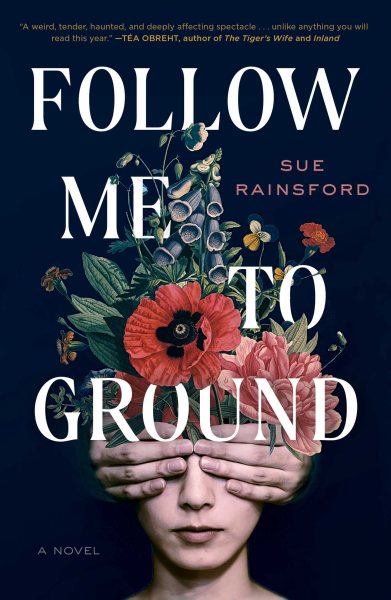

Sue Rainsford’s Follow Me to Ground is the story of Ada and her father, two not-quite-humans who possess the power to heal sickness by burying ill and hurt people, or Cures, in an area called The Ground. They live as semi-outcasts, both feared and revered by the local Cures, until one day when Ada begins a relationship with a man named Samson and their way of life is threatened by Ada’s awakened desires and Samson’s mysterious past. Part fairytale, part myth, with a touch of horror and a heavy dose of magical realism, the book is unsettling in the best way. Ada’s otherness allows us to see human illness at a remove and to consider what it might mean to be truly healed.

I met Sue Rainsford in 2007 when we were both studying at Trinity College Dublin. I was taken with her writing from the first time I heard her read and knew then that it wouldn’t be long before I held her published work in my hands. Since then, Sue has earned her MFA from Bennington College and has been the recipient of multiple grants from the Arts Council of Ireland, as well as a MacDowell Colony Fellowship. She is currently the writer-in-residence at Maynooth University in Ireland.

We spoke over video chat about writing desire and the female body, subverting the gendered tropes of writing sex scenes, and monstrous women in fiction.

Shayne Terry: One of the many things I love about this book is how viscerally it portrays the female body in various stages of life. The Cures that Ada works on are pregnant, birthing, menopausal, and she describes their bodies—and their bodily fluids—in clinical detail. The gaze is not a male one, but because Ada is otherworldly, it’s not quite a female one either. How did you approach writing the female body in this work?

Sue Rainsford: Going into the book, I had two concerns. I had just read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and had become really drawn to this sort of imagistic and poetic language that she and people, to a lesser extent, like Julia Kristeva use when they’re writing within this psychoanalytical or existential genre. They still find themselves going to this really dense, often metaphorical language to talk about the female body. And I wanted to question that impulse, why it’s so ingrained in us, as women, to write about ourselves that way, and also to tackle it a little bit. It sounds sort of paradoxical or oxymoronic because I’m writing through a sort of magical realist lens, but I wanted to see what would happen if the images ascribed to the female body were made play out in the real world. To look at the female body functioning, and this idea of fluid, that the leaking body or the staining body is this sort of infectious, contaminated vessel. This is what the female body is doing at all times: it’s making substances, it’s leaking substances, it’s holding substances or failing to hold its substances, and I wanted to focus on those processes that so often prove offensive to people.

I wanted to write about the female body functioning, and this idea of fluid, that the leaking, staining body is this infectious, contaminated vessel.

And then a big fixation of mine at the time of writing the book was how we as women—and women as an inclusive term—might experience our bodies if we weren’t so thoroughly enmeshed in Western discourse. So, for example, when Samson and Ada first have sex, Ada sees herself as swallowing Samson or consuming Samson. She doesn’t see herself as being penetrated or owned or invaded or perforated in any way. I was trying to look at female bodies without the backlog or the weight of gendered discourse. Obviously, it comes through because I’m a product of my environment and my education, but I was trying to, like you say, not fall into any of the conceits of the gendered gaze.

ST: And I think you accomplished that beautifully. Ada doesn’t start out having a vagina; it’s something that develops with her desire. Desire comes first and the organ follows.

SR: That is something that I included relatively late. I left the book alone for a long time, and when I came back to it, I realized, because I’d been looking at Kristeva, de Beauvoir, Elizabeth Gross, that a lot of the metaphors I’d been working with seemed reductive or biologically deterministic. I wanted to include something that broke out of too stringent a second-wave feminist template, something that shows how the female body can change and expand and grow into its own form, and again literalizing this idea that woman is not born, woman is made. She makes herself and her desire changes the topography of her body.

ST: The story has echoes of the Biblical story of Samson and Delilah, which many have interpreted as being about the treachery of women and the dangers of lust. Our Samson is also betrayed, but this story is more complicated. Ada is the superhuman one, and it is her powers she risks by pursuing the relationship. And though FMTG does explore the dangerous side of desire, there is no parable here. Sex and desire and even love are neither good nor bad in and of themselves, and the text passes no judgment on Ada’s desire. Was the Biblical story in your mind when you were writing, and did you intend to subvert it?

SR: Samson does come from the Biblical story, but I studied art history, and, especially with 17th-century Italian painting—Artemisia Gentileschi, Caravaggio—something that always struck me about Biblical painting of that timeframe was these huge, muscular men and this almost excess of male flesh. Same with the painterly depictions of women, but with the men, just the way Samson was painted, visually, this spent testosterone or this spent masculinity struck me. There’s something, within art history, transgressively sexual about a totally depleted male. I wanted to spend time thinking about a male body that is castrated in metaphorical ways.

There’s something transgressively sexual about a totally depleted male. A male body that is castrated in metaphorical ways.

I’m really glad you feel that there’s no judgment in those scenes. I didn’t want the book to be in any way polemical, but I did want to write a version of femininity in which Ada pursues her desires in an unapologetic way. There’s that story by Margaret Atwood about this woman who goes on a cruise, and she’s this black widow type who murders men and steals their fortunes. There’s a flashback in that story where you realize that one of the men she sets her sights on raped her when she was in secondary school. And I just thought, yeah, sometimes you get to kill your rapist. When it comes to female salvation within fiction, often the quieter moments are expected to resonate: the woman alone in her room afterward, having decided to take a higher moral high ground or having decided to sacrifice some element of herself. I wanted to counteract that.

ST: Ada certainly has the capacity for violence. She is also surprisingly uncaring toward the Cure women, almost to the point of cruelty—she heals them, but she has very little sympathy for their pain. How did you go about crafting this monstrous character while still giving the reader space to cheer her on? Because we do! We want her to be happy.

SR: It’s interesting that you observed her being uncaring toward the Cure women. As you know, I have endometriosis, so I have this long relationship with my gynecologist, who is wonderful, but as I was working on early drafts of the book, I was thinking about just how strange Western medicine is. You go to the doctor and they perform with you all of these strange intimacies. You’re in this emotional and physical proximity to someone you never see outside this room, and they glean all of this information from your body. They can tell things about you that you don’t know about yourself, just by looking at you. And that seemed to me the most intense form of violence.

I think people really identify with Ada because she’s so lonely, but she doesn’t know what her loneliness is. She’s been born into loneliness, and once she’s awakened to her desires, she feels them very intensely. And her relationship with Samson, which is hugely flawed and imperfect and holds all of these transgressive elements, maybe that’s what resonates with people, but I’m not sure to be honest. I’m still sort of surprised that people are on her side. Sometimes I think it’s that very basic writing conceit of giving a character desires and giving a character obstacles. But I’ll never get tired of hearing why individual readers side with her or cheer her on.

ST: Going back to this idea of sickness and the doctor/patient relationship in the Western paradigm—I, too, have a history of gynecological and obstetric issues, so this theme hit home for me. The book’s central question is really, “What does it mean to be sick, and what does it mean to be healed?” Ada and her father are not truly healing these people, are they? Part of what the Cures are searching for is emotional healing—I’m thinking of Lorraine, a Cure who keeps showing up even though, technically, nothing is wrong with her or Samson’s sister Olivia, who bears a moral burden over the paternity of her unborn child—but that’s not the kind of work Ada does. Father says, “Once they start talking heart and mind, you ask to be paid.”

It makes me wonder: what do we look for in our healers? Because illness can be traumatic. As Ada says, “a couple of the curings became local folklore and got told over and over, getting longer and stranger each time.” And isn’t that how we are with our worst sicknesses, turning them into stories, trying to find healing by putting a narrative to them?

We all live under the burden of the illusion of wholeness and that wellness or a consistent contentedness is an attainable thing.

SR: There is this strong connection between narrative and the healing process as we view it here in the West. And we sometimes conflate our sicknesses with our personalities; people blame themselves for their sickness, or your illness can start to have a real effect on your lifestyle. Reading Foucault’s History of Sexuality, there’s this idea that you used to go to the priest to confess and now you go to the doctor. As individuals in Western society, we’re so fixated on this idea of someone that you “go to” to divulge things about yourself, and they take all that away and they narrativize it and they compartmentalize it and they hand it back to you in a way you can digest. Therapists fill that role for people as well, but with a therapist it’s straightforward—that’s what they’re there to do. With doctors, people are going through this side door because maybe they don’t want to acknowledge fully what it is they’re looking for.

I love that you say the Cures are not really cured. We all live under the burden of the illusion of wholeness and that wholeness is an attainable thing, wholeness meaning wellness or a consistent contentedness. When Lorraine starts coming to see Ada, for example, Ada is confused because what Lorraine is dealing with is her menopause.

ST: The story has no stated setting or time period. We understand that it’s a rural farming community and that, sometime in the past, there was a war. Some have suggested that it takes place in the US, in the Deep South, partially due to the long days of heat and sun. But the story feels undeniably Irish to me, in both its lyricism and its subject matter: the forbidden, the female body, the mother. Are there particular Irish texts you felt you were in conversation with when writing FMTG?

SR: Yes! Eimear McBride’s A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing.

ST: I love that book.

SR: That close relationship between language and a girl’s growing awareness of herself was really important to me. And she just throws everything out the fucking window in that book. It was so freeing. That dense, dense unapologetic lyricism. I was just infatuated with it.

In terms of landscape, it’s funny because so many people have said it feels like the Deep South, and I’ve never been there—I would love to go—but I am really interested in how the atmosphere of a landscape bears down on a person and how consistent, intense heat affects your state of mind. Misty heat, when it’s hot in the morning and hot in the night, and there’s no respite from it, and how it affects the way you look at your body and feel your body. What sex is like in that kind of atmosphere because you’re just making yourself hotter by forcing yourself into proximity with another person. What it does to desire and what it does to even the most daily activity, even just being in the kitchen because the kitchen’s hotter anyway.

ST: But then The Ground itself is so reminiscent of an Irish bog, which can preserve bodies for centuries.

SR: The bog aspect of it came into the writing in a subconscious way. It’s probably one of the few big nuggets of the book that I didn’t curate, because it did start off as a quite conceptual undertaking, and I had to work to get it functioning as a piece of fiction as well. The very first scene used to be Ada and Father digging Lorraine’s grave, and that kind of came to me as this weird photograph when I was down in West Cork, surrounded by that very poetic, dramatic landscape. It’s not really the type of landscape that people think of when they think of Ireland. It’s rocky and arid and so much of it is untraversable because the gorse is growing in such dense knots. But it is very much Irish.

ST: A major theme of the book that we haven’t yet discussed is mothers. It seems to me that the text is writing around the figure of the mother. Ada has none. The Cures we meet who are mothers we see in the context of Ada saving their dying babies (except in the case when she doesn’t). We see Olivia pregnant, but we never see her in her role as a mother—and even then we know she is a sort of monstrous mother figure.

SR: Oh, she’s the worst, yeah.

ST: Father tells Ada that it’s “unspectacular business, coming into the world.” But that’s not really true, is it? FMTG is all about birth—how it comes about and the many ways it can go wrong.

We punish female bodies, but we really punish the maternal body.

SR: I love what you say about how the book moves around mothering; we see lots of mothers, but we don’t see them mothering their children. In Ireland, largely because of the Catholic Church, we’ve always had this problematic relationship with mothers. We punish female bodies, but we really punish the maternal body. All of these things were in my head while I was writing, Repeal the 8th [a movement which, in 2018, led to the Irish people voting to repeal the 8th amendment to their constitution, allowing the government to legislate for abortion], Survivors of Symphysiotomy—

ST: What is symphysiotomy?

SR: There were these women who were basically experimented on during childbirth in hospitals around Ireland, and who started speaking out and organizing in 2012. These women had had their pubic symphysis, the joint in the center of the pelvis, severed with, essentially, a saw to enable vaginal birth. At the time, Caesareans were considered a form of contraception and, of course, the Catholic Church did not approve of contraception. Catholicism is so entwined with the Irish state, with these religious orders behind hospitals, that you basically had these women being butchered so that they could proceed to have multiple children vaginally. And many of them weren’t even told that a procedure had been performed on them; they were just told this was childbirth. So they would go home, they might be incontinent, in acute pain for the rest of their lives, sex was agony, but very rarely did someone say, you were subjected to, without your consent, this vicious procedure, and that’s why this part of your body has been destroyed.

ST: That’s awful. I had no idea.

SR: At the time that I was writing, there was a lot of coverage about it. They put together this document for the UN and the UN classified it as a form of torture. All that was very much at the front of my mind, thinking about Lorraine especially and about what we punish women for. We ask female bodies to perform their childbirth function so thoroughly, and then as soon as you have fulfilled that role, then you’re spent and you move into another phase—a menopausal body. And menopausal bodies are punished for going outside of their prescribed boundaries, so a menopausal body that is feeling sexual desire is seen as gross and taboo. As I was thinking about this idea of uncompromising female desire, I also wanted to show maternal bodies doing all the things they’re not meant to do, to drop the maternal body into these situations where it’s doing things that we find horrific and asking then, why do we find these things horrific? Sometimes, of course, they genuinely are horrific, as with Olivia and the circumstances of her pregnancy. But the maternal body is something that we try so hard to control that it was interesting to me to try and provoke those templates a bit. And that’s something that I’m trying to do in my second book, as well—I haven’t quite gotten over that.