essays

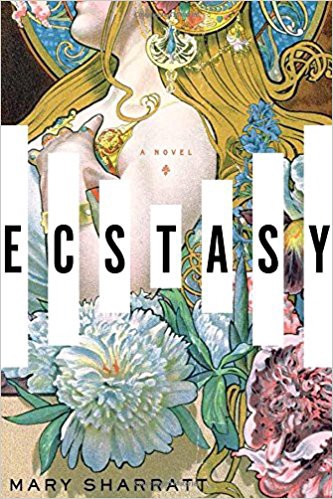

Writing About the Ultimate Party Girl Made Me Realize How Much We Limit Women

My main character seems like the opposite of my introverted self—but there’s more to both of us than meets the eye

Alma Schindler Mahler, the historical heroine of my new novel Ecstasy, was everything I am not. She was larger than life. An exuberantly extroverted diva. The It-Girl of fin-de-siècle Vienna. When Alma stepped into the salon in her white crepe-de-chine gown, the air crackled with electricity, so mesmerizing was her presence. Artists, architects, and poets vied for her attention.

Gustav Klimt chased her across Italy to give her her first kiss when she was just a teenager. Gustav Mahler fell in love with her at a dinner party and proposed only weeks later.

Her subsequent husbands and lovers included Bauhaus-founder Walter Gropius, artist Oskar Kokoschka, and poet Franz Werfel. But she was her own woman to the last, polyamorous long before it was cool, one of the most controversial women of her time.

I, on the other hand, am a wallflower. At parties, I struggle with small talk and spend more time listening than speaking. What do I have to talk about anyway? I sit in my study and write all day, then rush to the boarding stable to muck out my horse. Hardly the most scintillating cocktail party conversation — but I prefer long hikes to cocktail parties anyway. I would have bored Alma in real life, and she would have overwhelmed me. So why was I so drawn to her as a character, this over-the-top party girl who was more interested in currying male favor than currying horses?

The simple answer would be that I was attracted to Alma because I saw in her something lacking in myself — that I felt compelled to write about my unlived life, my imaginary cinema self who is far more sparkling, witty, beautiful, and courageous than I could ever be. This idea — that authors create the heroines we long to become — is the most obvious explanation. It’s also wrong.

I would have bored Alma in real life, and she would have overwhelmed me. So why was I so drawn to her as a character?

The truth is that I fell in love with Alma because she was like me. In her diaries, Alma revealed a secret self that made my heart leap in recognition. In these private pages, I discovered a cerebral and paradoxically lonely young woman. Most poignantly of all, considering everything that happened later in her life, she burned with the ambition to become a composer. This Alma was so unlike the cliché of the extroverted socialite and femme fatale. This Alma became my soulmate — a thing that on the surface seemed impossible.

In February 1898, having just returned home from the Vienna Court Opera’s performance of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, seventeen-year-old Alma wrote the following passage:

If only I were a somebody — a real person, noted for and capable of great things . . . I want to do something really remarkable. Would like to compose a really good opera — something no woman has ever achieved.

Alma was a highly cultured young woman who spent far more time reading or engaging with art and music than she did flirting at parties. She attended concerts, operas, plays, and art exhibitions several times in any given week. Her late father, Emil Schindler, was an iconic Austrian landscape painter and her stepfather, Carl Moll, was co-founder of the Vienna Secession art movement. Alma devoured philosophy books and avant-garde literature. She was a most accomplished pianist — her teacher thought she was good enough to study at Vienna Conservatory. However, Alma didn’t want a career of public performance. Instead she poured her entire soul into composing. Her lieder, written under the guidance of her mentor and lover, Alexander von Zemlinsky, are arresting, emotional, and highly original and can be compared with the early work of Zemlinsky’s other famous student, Arnold Schoenberg.

But the odds were stacked against her. Women who strived for a livelihood in the arts were mocked as the “third sex” — the fate of Alma’s friend, the sculptor Ilse Conrat. When a towering genius like Mahler asked Alma to give up her composing career as a condition of their marriage, she reluctantly succumbed.

Yet underneath it all she was still that questing young woman who yearned to create symphonies and operas. Shortly before her marriage, 22-year-old Alma wrote in her diary, “I have two souls: I know it.”

The times and circumstances Alma lived in all but forced her to enmesh herself in the lives of famous men in hope of being remembered at all. It’s only thanks to feminism that I have the liberty to hide in my writing cave instead of being decorative and charming in the salon. I could be my own person and follow my creative path because rule-breakers like Alma helped pave the way for me.

In terms of conventional “morality,” I am no better than Alma. For all her reputed promiscuity, I probably dated more people during my undergraduate years in college than Alma did during her entire life. My romantic escapades would have branded me a fallen woman — or worse — had I lived in Alma’s time. Never mind the fact that in turn-of-the-twentieth century Vienna, it was extremely rare for women to attend university at all. Entire faculties, including the School of Medicine, were barred to female students.

Realizing how similar I was to this ultimate party girl made me realize that ideas like introvert and It Girl are artificial and limiting. What Alma taught me is that there are no good women or bad women. She taught me the value of being fully, authentically human, whatever the cost. She drove home the point that pure and impure, faithful and loose, madonna and whore are simply poisonous projections used to deny women their full expression of being. Alma was not any one color, dark or light. She was the whole spectrum. So it is with all of us. Regardless whether we’re cloistered introverts or glamorous socialites, every woman contains the totality, the heights and the depths.