Lit Mags

Never Marry a Man with a Human Mother

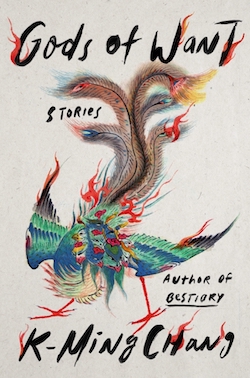

"Xífù" from GODS OF WANT by K-Ming Chang, recommended by Bryan Washington

Introduction by Bryan Washington

As rough as they’ve been, the past few years have provided a prodigious expansion of the English language’s queer canon. I’m stoked just thinking about it. We’ve not only seen queer narrative forms expanded (and contorted, and reconstructed, and flipped on their heads), but also loads and loads of this has been accomplished through each author’s individual, singular terms. We’ve been privy to an eliding of normative structures. So many of these stories have decentered whiteness (and white people) from their conceptions of queer futures. It’s all been amazing and cute. Because when a writer trusts themselves to follow the expansiveness of their vision to its terminal limits, and then a little bit further, we all ultimately benefit: our sense of the possible, and the many different ways there are to be, expands alongside them.

I say all of that to underline just how brilliant K Ming-Chang’s work is. Her novel Bestiary completely upended me. Her prose contorted my sense of just what, exactly, words on a page could do. And Chang’s chapbook, Bone House, is similarly discombobulating, while simultaneously honed and precise, languishing (but only briefly—it’s a novelette) in a queer Taiwanese-American retelling of Wuthering Heights. So, having read these works, I would have pre-ordered Chang’s next endeavor even if it had been to rewrite the Encyclopædia Britannica. Then I would have bought like five more copies for friends.

I say all of that to underline just how brilliant K Ming-Chang’s work is. Her novel Bestiary completely upended me. Her prose contorted my sense of just what, exactly, words on a page could do. And Chang’s chapbook, Bone House, is similarly discombobulating, while simultaneously honed and precise, languishing (but only briefly—it’s a novelette) in a queer Taiwanese-American retelling of Wuthering Heights. So, having read these works, I would have pre-ordered Chang’s next endeavor even if it had been to rewrite the Encyclopædia Britannica. Then I would have bought like five more copies for friends.

Her new short story collection Gods of Want, both widens and calcifies the expansiveness of her range. A blessed many authors are doing this today—and so many of them are queer—but Chang is singular amongst us all. She is really fucking good at her job.

The short story “Xífù” is a delicious example of this masterful push. In lieu of a summary, I’ll simply say: please read it. It’s so good. It investigates familial relationships with humor and emotional depth. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t add what feels like a crucial detail: Chang not only accomplishes narrative reinvention in her writing—she builds upon what feels achievable on the page. Chang shows us different ways of being. And different ways of moving. Even when her work utilizes the I, her prose feels rigorously and generously ensconced in the us. We. Ours. For me, new work from Chang is a cause for celebration—a holiday in its own right—and it’s also a reminder of the infinite possibilities on the page. That she’s able to conjure so many pathways—without insisting on answers or conclusions, only more ways of being—is nothing short of marvelous. I’m very grateful. We’re very lucky!

– Bryan Washington

Author of Memorial

Never Marry a Man with a Human Mother

K-Ming Chang

Share article

Xífù

I don’t mean I want her to die. I’m just saying, what kind of woman pretends to kill herself six times? I’m saying that she loves to pretend. Some women are like that. They don’t know what real means. Like that neighbor I had back on the island who pretended she was pregnant for three whole years. Her belly was a sack of guavas, all lumps, and she really thought no one would be able to tell. One of the neighborhood boys punched her in the belly to prove to his friends she wasn’t actually pregnant, and all the guavas came rolling out the bottom of her dress and down the road. Juice sprayed everywhere and greenmeat jellied between her feet. And that woman cried about it too. She cried so hard and so long that the sea came forward and punched her out for spending so much of its salt. Some women will mourn anything, even things that haven’t been born. I know a story about another woman on the island who impregnated a goat. In the dream, the woman masturbated—don’t believe anyone who says she’s never touched herself, she’s probably touched herself with all kinds of things, a karaoke microphone, an assortment of vacuum-cleaner attachments, a fake jade statue of Guanyin—and then offered her salted palm to her goat, which licked it clean with its tongue.

Three months later, the goat got big in the belly and the woman cut it open. Inside, there was a baby. She raised it all by herself. The baby walked on all fours for its whole life, even when it was a girl, and you can imagine what the boys thought of her. They probably mounted her like a dog on the street. The goatgirl had a baby every four days, I swear. That’s the story I heard. And she ate grass too. Her mouth was always grazing the ground. What I always wanted to know was what happened to the goat after it got cut open? How did they cook it? Kebabs? Goat dumplings? Spit-roasting the whole thing?

That’s why I told my daughter not to marry a man whose mother is alive. Best if the mother is a goat or dead. That’s the only requirement I have: Don’t marry a man with an origin. Set his family on fire. But she tells me it’s okay, that she’ll marry no one’s son because she’s a lesbian, and I’m so jealous I could kick her in front of a car, the way I once did to the neighbor’s pit bull when it shat maggots on my feet. There aren’t even any cars that come down our street anymore—they stopped coming since the police roadblocked the strip mall. They busted that massage place in the plaza, said it was full of Chinese prostitutes. I called the newspaper to clarify: I’m Taiwanese. I used to work there. At night I slept with all the other women, some from the mainland and some from the island and some from other islands too small for even the sea to know them. We slept in that hot back room, folding away all the tables and knotting together like a litter of pigs. The tatami mats were plastic and gave me rashes, but sometimes it was okay too, sometimes I liked hearing those women breathing all around me, all the heat in our bodies enough to burn down the building.

I ask my daughter how you even become a lesbian and she says, first, I have to reject the male gaze. So I tell her the story of my father, who couldn’t see except for the shadows of things. She says, I’m not talking about literal sight. But I am. I’m talking about literally being seen. Like the time before my daughter was born when my husband caught me dipping my finger into the toilet after I’d peed in it. I licked the finger clean. Thing is, I was told that that’s one way to make sure you have a daughter. A neighbor told me that, the same neighbor who got caught shoplifting eggplants. Told her, Eggplants aren’t even good. Anyway, I got a daughter, didn’t I? A daughter who doesn’t have to worry about her mother-in-law moving in like mine did. I swear, that woman cut holes in my clothes and pretended moths did it. I’ve never had moths. I kill those motherfuckers with my own bare hands. I clap them down like wannabe angels and crush with my heels their brittle haloes.

I once threw a pencil at a fly and pierced it through the heart, if flies even have hearts. My mother-in-law saw me and said that was my aborigine blood, that habit of skewering things alive. And another time she picked up all my dishes after I’d washed them and said they weren’t clean enough. They’re clean enough to see your ugly face with, I wanted to say. Almost told her, Go eat out of your own ass, that’s all your mouth is good for. She tried to move into the bedroom with me and my husband. Said some fei hua about how her room down in the garage was too close to the kitchen, which has a microwave, which will kill her with its rays. Wanted to microwave her head until the brain-yolk dribbled hot from her ears. The first time my mother-in-law pretended to die, she staged a fall. She went into the kitchen and wet the floor and threw all my plates to the ground. Those plates were what I brought here from the island all those years ago. Everyone told me not to take fragile things onto a plane, because they break. Something about air pressure or the sky’s weight. But all the things I packed were breakable. I brought a glass ashtray that my mother once threw at my father’s head. It hit him in the eye and now he can’t see the meat of things. He can only see their shadows. So that he could see where my hands were, I had to shine a flashlight on them, cast their shape on a wall. I keep the ashtray to remind myself I have a shadow. Sometimes you can’t tell what’s a body or what’s a shadow. For years I stepped around this big spot on the sidewalk I thought was water or piss or something. Turns out it was the shadow of a tree I hadn’t looked up to see. I look at the ground more and more these days. Better to keep your eyes where your feet are.

Anyway, my mother-in-law lay down among all the things (mine!) she broke and pretended she’d fallen on the wet floor. Fallen doing what? The woman doesn’t do anything but follow me around all day and tell me to take her to the dentist. Claims she’s got teeth cancer, sometimes jaw cancer. Is there even such thing? For all I know, I’ve got jaw cancer. I ran to my mother-in-law and helped her up, but I could see there was no bruise on her. The only thing she’d done was bite her tongue a little, and it wasn’t even bleeding. I’d give her my blood to bleed with, that’s how generous I am, but she’s never been hurt in her life. After that, she insisted on walking around the house using a broomstick as a cane. I’ve seen that woman jump three feet into the air to smack a mosquito with her hands. One night I saw her drop the cane and run to the TV so she could catch the opening scene of her soap opera, about an empress dowager controlling her puppet son. You see how fake?

I could push her feet into a pot of hot water and boil them till they rise like dumplings. I could scalp her and then wear her skin like a swim cap.

Then the second time she tried, it was with a rope. She tried to hang herself in the pantry, except when I opened the door, her feet were still on the ground. Sure, the rope was around her neck and tied to the rafter and everything, but the pantry’s only four and a half feet tall and she was just standing there, leashed to the ceiling. She even tried to pretend she was choking by sticking her tongue out and making these coughing sounds, but when I asked her what the hell she was doing, she paused to say, I’m killing myself because you are a bad daughter-in-law and what will my son think when he finds out I’ve killed myself because of you how bad he will feel how much he will regret marrying you choosing you you bitch. I said, If you can say all that while hanging yourself, you’re going to live. And the third time was the worst. She stole the neighbor’s kiddie pool and filled it up in the yard and pretended to drown in it. Except she didn’t fill it up enough and there was only about a knuckle of water in there, and when she thrashed around, most of it splashed out of the pool and then she had to continue pretending to drown in nothing. She flopped facedown and tried to be dead, but the whole pool deflated from the weight of her body—let me tell you, she’s got hips like hams— and as the air came out, it made a farting sound. Instead of dying, it sounded like she needed to shit. The fourth time was also a drowning, except this one was in the bathtub. I heard her filling it up and I was ready this time. As soon as she got into the tub with all her clothes on, I burst through the door, said, Not while I’m alive, and dragged her out by the hair. Turns out her hair is not very strongly attached to her scalp, so I ended up tearing out a lot of it, and she cried for almost a month about it, told my husband I was abusing her and now she’d have to wear a wig. I know ways to abuse her, and none of them involve her hair. I could heat up a frying pan and press it to her face until the skin sizzles and all her features melt together into an abstract painting. I could push her feet into a pot of hot water and boil them till they rise like dumplings. I could scalp her and then wear her skin like a swim cap.

All my friends say what I’m dealing with is nothing: They have mothers-in-law who have locked them inside the garage on 105-degree days, that have put manure in their food and claimed it was the recipe, as if they have ever used a recipe. The worst thing is when some of them convert our children into loving their nainais better than they love their own mothers. That’s when you have to tell your daughters the truth of everything that’s been done to you, all the times you were told you were a bad xífù for eating with your head bent over the bowl, for shopping at Nordstrom Rack instead of going to the temple, for overstuffing dumplings into testicle-looking things. So what if I like them big. And then you tell your daughter all the stories in history about mothers-in-law who beat concubines to death with a chamber pot, mothers-in-law who rip themselves open by shoving their sons’ full-grown heads back inside themselves, sometimes up the wrong hole, a mother-in-law who wakes you up at three in the morning so that you can drive her to the emergency room because, she claims, she’s pregnant at the age of seventy-seven and is having a baby right now, it’s inside her, rolling around like a juiced grapefruit, it’s sour and screaming, and when you finally get there, an hour later because she tells you there’s a shortcut even though the only direction she knows is toward the church, it turns out she has kidney stones and you’re going to have to pay for their removal, out of pocket, and the rest is debt you’ll have for life, and when the doctor rolls her into surgery, you tell him, Please just let her die on the operating table, or Please pretend to operate on her but leave the stones inside her, make her feel the birth-pain of passing those blessed pebbles through her body.

But the doctor doesn’t listen, he removes them and then stitches her up and she loses basically no blood, and she goes home the next day and tells you it’s your fault for using too much soy sauce in all your dishes, even though the reason you add a spoonful more is that she told you in the first place that nothing you make is salty enough. The fifth time she tries to kill herself is when she walks out to the highway—without her cane, of course—and steps in front of an 18-wheeler, except by some miracle, the 18-wheeler stops right before it hits her and there’s an eight-car pileup and we see her on the local evening news. It’s a physics-defying miracle, how an elderly woman who is terribly neglected at home—because of course she has to say that on TV—has been saved thanks to a trucker’s quick reflexes and the benevolent will of god. She’s being called a saint in certain comments sections, and I might have left a comment or two as well, all of them about how people aren’t really supposed to live forever, in other eras they would be dead by seventy-seven, and being pulped by an 18-wheeler is actually, I imagine, a very merciful end, and it probably leaves a beautiful piece of blood-art on the highway, kind of like a mural you can only see from above.

They even interview her for the World Journal, and of course she tells the reporter she doesn’t blame her daughter-in-law for not taking better care of her, because how can a woman like her, at her age, be valued in a world like this, where old women are seen as burdens? But god had said oth erwise; god had held back an 18-wheeler and said, You are worthy of my love and intervention. I almost strangle her in her bed after that. I stand over her in the dark and think about it, just think about it. The sixth time, I tell my husband it’s all his fault. He should have been immaculately conceived by a goat. Every man loves his mother milk-sour. I tell you, my husband never once took my side. One time my mother-in-law told me I’d overcooked the fish, but that fish was so soft inside it almost dissolved in the light. And my husband said nothing to defend me, even though he’d eaten half the fish himself, and my daughter the lesbian only knows enough Chinese to say, I don’t want, thank you. Like a damn cricket, she says it again and again. I want her to tell me my fish is done perfect. Look how the bones disrobe. This woman tells me I can’t cook a fish? I’ll cook her. Later she says she wants the master bedroom because the garage is full of outside-air, and outside-air is full of toxins that are souring her, can’t you see how her neck sags, how her breasts are hard as potatoes, how her tongue is purple? I want to say, Your neck sags because you’re an old shit-sack, your breasts are hard because you don’t take them out to breathe, your tongue is purple from that time you bit it instead of dying.

Being pulped by an 18-wheeler is actually, I imagine, a very merciful end, and it probably leaves a beautiful piece of blood-art on the highway, kind of like a mural you can only see from above.

I don’t say anything about the fish, and I don’t apologize either, so that night she puts her head in the oven but forgets to turn it on. I come downstairs in the morning and she is asleep, drooling, with her head poked into the oven. I ask her where she learned to do this oven thing and she says she’s been reading, even though I know that woman is illiterate. She’s one of those peasant women who’s so short she looks like a pack animal from afar, a body built to carry things. I’m a better mother to her son than she is. That’s what marriage is, motherhood, except the man doesn’t do you the courtesy of growing up. I tell her, Next time just swallow the insecticide we keep on the shelf in the garage. She looks at me angry, because I am supposed to say, No, don’t die, we need you, your son needs you, etc. I bend down really close to her face and say, The oven is electric. Then I tell her, The way gas works, you could have killed everyone in this house. Is that what you want, to kill your own son in his sleep?

And that’s when she stands up, a foot shorter than me. It’s morning and my daughter is waking up. I can hear her in the next room, walking around without socks on even though I tell her you can die that way. I like to be awake before she is. I’m glad she won’t have a man. Better not to be a mother. It leads to many suicides, I should tell her. My mother-in-law starts telling me this story about how she didn’t know she was pregnant. The night her son was born, she thought she was having gas. She was alone. But then my husband slipped out of her like a fish and everyone said, Kill it. That’s when she left for the island, the baby dragged behind her in a net. I call her a liar. I won’t forget the time she caught my husband washing a dish and called my own mother in Yilan to complain how I wasn’t doing my duty as a wife, how I made her son clean in his own home, how I threatened him with a back scratcher into rinsing that dish, and of course my mother believed this and called to tell me I would never grow skin, as if, as if my husband has ever washed a dish, as if he’s ever washed anything but his own dick, and even that not very well.

The problem is this, I tell my daughter: Mothers grow up married to their sons, but we’re born knowing our daughters will leave us. Not because we want them to, but because we never had them, not really: They belong to the men we give them to. Men, they belong to everything, including themselves. This is what I say: We should separate all mothers and sons at birth and grow them in different dirts. Make the sons grow up alone. And mothers, we’ll be fine in our own rooms. Give us a window or two, a view, curtains that open into morning. All those times she almost killed herself, she didn’t know death isn’t like a man: It won’t just take you anytime you’re on your back. When she finally dies, I won’t pretend I’m not happy about it. But I’ll buy her a good burial, a full funeral. I’ll give her an urn with a name on it, which is more than her family would have done, her family who doesn’t even name their daughters. That woman answers to nothing. I can’t even pray her dead, because the gods don’t have her listed in any directory. When my husband dies, I’ll bury him beneath her. And I won’t mourn then either. You can have his bones and the moths they’ll become. I joke now with my daughter, not that it matters to her, since the only men she’ll marry are women, and two women together probably cancel out, become nameless. I point at the sky. The sun, I say, and laugh. When choosing a sun to see by, make sure it’s got no mother. The moon, that’s the mother. Her eye is always open to watch her sun. It’s not really a light, my daughter says about the moon, it’s a mirror. But mirrors, I tell her, are more dangerous than anything. A mirror’s only meaning is to multiply. To duplicate. To duty. The mirror doesn’t change what is shown to it, not unless someone shatters the glass, and that would be you, my daugh ter, the fist to my ribs, the one who will never become the moon.