Books & Culture

My Great-Grandmother Knew Our Indigenous Songs had the Power to Heal Our World

In the early days of the pandemic, I found strength in the story of how she convinced a famous composer to write a Coast Salish symphony

In 2006, I watched my great-grandmother address a sold-out crowd at Seattle’s Benaroya Hall. She climbed the wooden steps of the stage, her small frame draped in her wool shawl, and I watched as her father’s painted drum was handed to a percussionist in the orchestra. My great-grandmother, my namesake, turned and addressed the audience. She spoke about the First People of this land. She talked about a need for healing. “People,” she said, her heart breaking for a wounded world, “have lost their way.”

Her father’s drum sounded. The first powerful beat reverberated like thunder.

14 years later, my mom sits at her desk, a mosaic of script pages laid out around her. She’s studying the opening scenes, the interviews, and the movements of the music. She’s finalizing what will become the documentary of my great-grandmother’s symphony. She looks up from her tiles and tells me, “This must happen now. People need to hear this music again.” The footage for the documentary has sat unused, dormant for all these years. Until now.

That spring, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, police officers murdered George Floyd in the streets of Minneapolis. Protests erupted around the country, and cop cars burned in the streets of Seattle.

My great-grandmother was 83 years old when she commissioned The Healing Heart of the First People of This Land. She had been troubled by the world. Back then, in 2001, the news was all about George V. Bush’s war on terror. She saw beyond the fear. She saw a country divided, the wars across the ocean and the violent injustices in her own streets. She saw that the people had lost their way. She believed so deeply in our people’s stories, the teachings inherent in them. She knew that no one would listen to an old Indian woman, that she would have to reach them another way. Somehow, she arrived at what she called highbrow music: symphonies. This came as a shock to us. My great-grandmother hadn’t grown up with this kind of stuff. She loved square dancing and Elvis. But she believed this was the way, that if all people could experience our beliefs through song, the music could heal the wound. She needed something that everyone could hear. She called a famous composer. “I need you to write a symphony,” she demanded, “and to perform it at Benaroya Hall.”

The composer turned her down.

She knew that no one would listen to an old Indian woman, that she would have to reach them another way.

But weeks after the call, he couldn’t get this 83-year-old Indian woman’s voice out of his head. He called her back and together they collaborated on a symphony, the first to be based on Coast Salish spirit songs with lyrics in Lushootseed, the traditional language.

In our longhouse ceremonies, songs hold a spiritual power. There are certain songs for prayer, for healing. My great-grandmother had a cassette tape with recordings of two spirit songs: one belonged to a beloved cousin, and the other was Chief Seattle’s thunder spirit song. She entrusted the tape to the composer with instructions to listen to but not share them. She wanted the songs to guide him as he wrote the symphony. She hoped that the healing power of these spirit songs would take shape in the symphony and that when people heard it, they might be touched by that power. She was hoping for medicine, for a world that could change.

On a hot summer day in 2020 I stood thronged in protest, in collective grief and anger. We yelled, we chanted, we demanded justice. I raised my cardboard sign that read in bold letters indigenous solidarity with Black Lives Matter . But it didn’t feel like enough, would never feel like enough. Weeks went by. Weeks of flash-bangs and tear gas. Weeks of protesters being arrested and assaulted, until finally the people took over the precinct. With the police gone, the organizers secured six Seattle city blocks, declaring it the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. There were medical tents and tables of free books on political education. People brought crates of food to share, while others held demonstrations. My partner and I walked the streets of a free Seattle, watching films being projected onto buildings, seeing murals painted over boarded-up windows. There were large plastic bottles of hand sanitizer duct-taped to telephone poles.

It seemed as though the people had created a utopia. Until it didn’t. We turned a corner to find the park in the center of the autonomous zone in full-blown festival mode. Kids in droves wielded glow sticks. It looked like Coachella. It looked like Burning Man. People were drunk, waving selfie sticks instead of placards, wearing angel wings and carrying Hula-Hoops. Is this what change looked like?

But in the middle of the intersection, we found a gathering of Coast Salish people. I watched as men laid out large cedar boughs in a circle. Then women entered carrying burning bundles. The cedar smoke wafted over the crowd, the tents, the abandoned precinct. They were sharing their medicine.

Would I feel safe again? Would the world feel safe again?

When the first speaker approached, he asked that any and all Coast Salish and Indigenous people come forward to the edge of the circle. He asked that the white people step back for us. I looked at my partner, who looked at me, then gently let go of my hand. A young woman stepped away from her girlfriend and together we both stepped forward, away from our white partners.

“Before we begin here today,” the man with the mic yelled, “I want to honor our elder Vi taqʷšəblu Hilbert. It’s important we remember her, here on her land, for the work she did for the Coast Salish people.” The man spoke in Lushootseed and in English. He introduced a group of Coast Salish singers. They made a half-moon around the burning cedar and hit their drums hard. I closed my eyes and saw my great-grandmother as she stood on stage at Benaroya Hall fourteen years earlier. I saw the painted drum, heard its heartbeat as it boomed like thunder, as it called out for change. I hadn’t heard my great-grandmother’s name, her Skagit name, the name we shared, spoken in a very long time.

The symphony had been her last project; she passed away before the documentary could be made. But right up until the end she went to gatherings, to speaking events, events like this. I had seen her small and frail but still so powerful when she spoke. I thought of her here today in this crowd and shuddered at the imagined worry. Even amid the threat of this pandemic, she would have been here. I let the drums wash over me as I cried, transporting me to the smoke-filled longhouse, my great-grandmother’s hand on my shoulder as we listened.

Throughout this pandemic I return to the books my great-grandmother made, the ones that house our language and our stories. Some days I spend crying, curled in the crook of my partner’s lap as the cats and dog wander the house, charged with an animal anxiety. Some days I make salmon and black coffee, simply to fill the house with the familiar aroma of my great-grandmother’s kitchen. All these white women on Pinterest are baking loaves of sourdough, and I am trying to time travel.

We climb out onto the roof of my house and watch the sky change. The world has stopped, but it feels even more frozen on the reservation. I have good days and bad days. We make a game out of our once-a-month grocery shopping. We call it the Hunger Games. We call it the Soft Apocalypse as we wait in line outside the Trader Joe’s, masks on and six feet apart from everyone but each other. We dress up at night, light all the candles in the house, eat the fanciest meal we can muster, and drink wine like expats in Paris.

We spend the summer locked inside, only able to be outdoors for 15 minutes at a time. Beyond that it’s too dangerous, as the smoke from the wildfires ignites my asthma. I boil pots of cedar and rosemary to help me breathe. And still people are dying in record numbers. We are losing our elders and I try to find my breath. I look for a mountain I can no longer see, its peak enveloped in smoke. A thick blanket of haze conceals the islands I know are out there dotting the waters beyond the shore.

There is a belief in my Coast Salish culture that songs have the power to heal, that they can be medicine.

On election night my partner and I sit barefoot on the floor, nervously checking our phones. We scroll. We put them down, then anxiously pick them up again. We do this until I can’t take it anymore. “How is this even an option?” I hold up my screen showing the very close count. I am afraid as a Coast Salish woman, a female-bodied person, a queer person. I am afraid for the people still being murdered by police, for the elders still threatened by the pandemic. I am afraid for how many times I might have to endure another aggression from a person who refuses to wear a mask but still clings to their MAGA hat like it was a prayer. Would I feel safe again? Would the world feel safe again? My partner picks up his guitar and strums the opening chords of one of my favorite Ramones songs. I join in off-key and giggling. By the time we reach the chorus we are hysterical, barely able to get the lines out. We make it through the song only to roar with laughter and begin again. There is a power in the repetition. We let the song transport us. In her own home on election night, my mom is not scrolling the news. She is pressing play, pause, and rewind, busy transcribing interviews, busy sorting through the raw footage of that day at Benaroya Hall. Again and again, her grandmother illuminates the screen, paused in smile, in speech. Occasionally the music floats through, the symphony inspired by a Coast Salish spirit song. In the interviews my great-grandmother talks about her anxiety for the world, her rising concern, but there is something confident in her smile, some glimmer of hope when she speaks about the power of song.

“People have lost their way,” she says. “They need to be reminded to take care of one another.”

There is a belief in my Coast Salish culture that songs have the power to heal, that they can be medicine. My great-grandmother wanted to share that knowledge, she wanted to remind people to have compassion, she wanted to change things. I don’t know anything about symphonies or orchestras. I don’t know any spirit songs. But as we sing out loud until two in the morning on election night, we are no longer checking our phones. We are not thinking about the president or the pandemic. We are laughing, lost in the music, lost in trying to get it right, lost in a brief moment of hope. We are singing, we are dancing.

We are trying to heal.

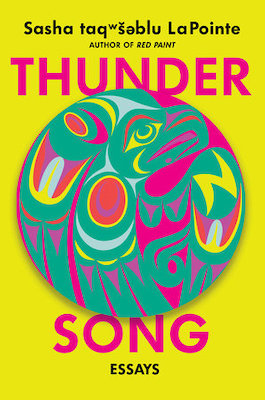

Excerpted from Thunder Songs: Essays. Copyright © 2024, Sasha taqwšəblu LaPointe. Reproduced by permission of Catapult. All rights reserved.