interviews

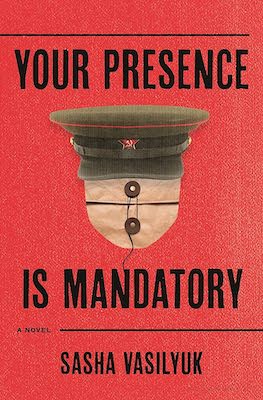

A Secret Letter to the KGB Turned A Lost Family History Into a Novel

Inspired by her grandfather, Sasha Vasilyuk’s "Your Presence Is Mandatory" is about the reverberating consequences made by a Jewish Ukrainian soldier in Stalin's army

Journalist Sasha Vasilyuk’s debut novel Your Presence Is Mandatory is a poignant look at the reverberating effects of war through the story of a Ukrainian World War II veteran’s struggle to hide a damaging secret for the sake of his family.

Vasilyuk’s book begins with death—the first chapter featuring a family at the grave in Donetsk, Ukraine of main character Yefim Shulman, paying their last respects. Shortly afterwards, his wife finds a letter in his belongings addressed to the KGB, a confession that launches the family to reconsider the man they thought they knew. The novel then takes the reader back to Yefim as a young soldier in Stalin’s army stationed in Lithuania in 1941, shortly before Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union. Yefim’s experience as a soldier left him with a secret he was so afraid to reveal, even to his own family, that he took it to his grave.

The book skips between Yefim’s experiences serving in Stalin’s army and the remainder of his post-war life in Ukraine, even extending 7 years after his death to the beginning of Russia’s occupation of Crimea and the start of war in Donetsk. Your Presence Is Mandatory is a timely look at survival that will make you question how wars, both past and present, shape future generations.

I interviewed author Sasha Vasilyuk over the phone about the discovery of her grandfather’s letter to the KGB that change her family narrative about who he was.

Katya Suvorova: Sasha, you’ve talked about how, after your grandfather’s passing, your grandmother and aunt found a real-life secret letter that your grandfather wrote to the KGB that totally upended your family narrative about who he was. How did this letter inspire Your Presence is Mandatory?

Sasha Vasilyuk: My grandfather was a Jewish Ukrainian World War II vet, but he didn’t ever talk about the war. From the few things that I and the rest of my family knew, we thought of him as a war hero, because he survived from the first day of the war until the last day four years later. Given that WWII killed 27 million Soviet people, this made him seem like a brave and lucky soldier. But his letter, which was addressed to the KGB and written back in the 1980s, revealed a very different story. Imagine thinking of your grandpa as a star of Inglorious Bastards where Jewish soldiers take revenge on the Nazis and finding out he was more like The Pianist. The letter was a shock to my family, but I immediately thought: this is a novel. I wasn’t just interested in how he survived WWII, but also in why he’d kept it a secret his whole life. Interestingly, it took my grandma several months to tell me about the letter because she too wanted to keep his secret a secret.

KS: Why do you think your grandmother hid the letter from you?

SV: So the Soviet government punished and shamed those who survived the war in non-heroic ways. That shaming culture was so strong that even after the USSR fell apart, people who’d internalized that shame continued to feel it. I think my grandpa, who inspired the main character Yefim, didn’t tell us what really happened to him during the war first to protect us from the government and later because he was ashamed. When my grandmother and my aunt discovered his letter, they also felt ashamed. At least at first.

KS: So do you think they finally accepted that he was a victim and that’s what brought them to tell you?

SV: I think they realized their shame stemmed from decades of propaganda and of living under a regime of fear. And maybe they saw that hiding one’s past makes it easy for future generations—like me—to not know your family history, or even your national history.

KS: I was reminded frequently while reading your novel of the parallels between passages describing the destruction and occupation of Ukraine by Nazi Germany in World War II and contemporary news reports of the Russia invasion of Ukraine. With your family being from the Donbas, how did your personal experience with Russian occupation affect your characters?

SV: After my grandmother found the letter, I didn’t sit down to write this novel for the next 10 years, primarily because I couldn’t imagine writing about World War II. It felt entirely too daunting. I felt like I couldn’t imagine what it was like to survive a war, even if I’ve seen the movies, like we all have, and read other books. As somebody who was trained as a journalist, I couldn’t write about war until war broke out in my family’s town in the Donbas. This was in 2014 and I visited in 2016 when it was supposed to be safer.

There, I heard shelling. I saw bullet holes on every surface. I saw the way people scurried about and I experienced the fear of war. And only then did I feel like I could portray those feelings in my characters with any, you know, realism.

As far as how it affected my characters, what I was surprised by was how the war changed how my family identified themselves. They shifted from this sort of a general Soviet identity, where we’re all brothers, toward a more nationalistic identity that very clearly distinguished Ukrainians from Russians. Now that we have a full-scale invasion this shift in identity really took over the entire Ukraine. There have been so many essays on this subject and so many people in Ukraine talk about how they’ve been perceiving themselves very differently because of the war. So when writing my characters, I thought about how war changes our identity and our relationship to home, to the state, to the enemy. Those things were all interesting to me.

KS: On the subject of parallels across the 20th and 21st centuries– I was impressed by how clearly well-researched each scene is regardless of time or place. A story across 70 years and numerous locations can be daunting as a writer, but you made the changing of the times feel seamless and grounded, while highlighting the cyclical nature of history. How did you approach the research necessary for this book?

When writing my characters, I thought about how war changes our identity and our relationship to home, to the state, to the enemy.

SV: So because the book has two timelines, one during World War II and one from World War II until the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, there are basically two parts to the research. And interestingly, the World War II part was much harder to research because I needed to find firsthand accounts of survivors. But because I was dealing with a part of history that was associated with shame, very few people ever talked about it publicly. I couldn’t ask my grandparents because they were both dead by then. So it took a long time to figure out how a Jewish person—a Jewish Soviet soldier—could have survived in Germany for four years. It was a question I asked of a famous historian, and he said he had no idea. Eventually, I found a book on this exact very narrow subject done by these two Soviet Jewish historians who had interviewed a bunch of soldiers.

KS: What was the book called?

SV: The title translates to “Doomed to Perish.”

If I didn’t find that book, I don’t know how I would have written this. For the decades taking place in the USSR, there was a lot of information. I relied on a mix of books, Soviet films, which I watched while nursing my newborn, Russian internet forums, and then interviews with my living relatives, and to some degree, my own memories. I lived there until I was 13.

KS: History repeats itself not only in war but also in regards to restrictions on freedom of speech. While we would like to believe survival is no longer dependent on keeping secrets such as Yefim’s, many across the world are unable to speak openly about their experiences without risking the safety of themselves and their families. What insights have you gained regarding censorship, both governmental and self-imposed, through the research and writing of this novel?

SV: I think that censorship and propaganda go hand in hand. Censorship creates a vacuum through misinformation and it’s typically propaganda and myth that fill that vacuum. So, for example, in Russia, World War II was always portrayed as this huge national trauma which USSR triumphed over. Basically, that’s the narrative. And while that narrative is true, what it skips is all the trauma that was inflicted by the USSR itself on many survivors of the war. And without that information, the following generations perceive the war very differently than it was in reality. Today, Putin’s regime uses this gilded myth of World War II to justify the war in Ukraine.

And then I’d say like on a personal level, self-imposed propaganda creates a vacuum within the family, where the information that would have been key to understanding your past as a family is missing. Like my grandfather not telling me what happened meant that all I knew about World War II was from the way it was taught to me by Russian textbooks, right? Had I known what he survived, my understanding of my country would have been entirely different. It is important to know that your people have done bad things to others or to themselves. That’s true of Russia. And that’s true of America. If you don’t know that, your understanding of yourself can be quite different. I feel like almost every Soviet family contains a secret that didn’t get passed down to today’s generation and it’s causing a very misguided understanding of ourselves and our history.

KS: I was really moved by how Yefim’s family handled his secret once they found out. I wish he had gotten to see their reaction while he was alive. How do you think he would have felt? Do you feel his family was able to find the closure that eluded Yefim?

I feel like almost every Soviet family contains a secret and it’s causing a misguided understanding of ourselves and our history.

SV: So, in my family, I think because there was no conversation that happened between my grandpa and us, it has been hard for us to get closure, even after finding this letter. We’re in a position where we know the truth, but what we don’t know is how it must have felt for him to live with the secret for so long. So, ironically, finding this letter has caused an enormous feeling of regret and even guilt on our part because we as a family have been left to wonder what we could have done differently to help him open up. Like was it our fault that we didn’t ask enough? Why didn’t we make him feel like he could trust us with his secret and his shame? And rationally, we understand it’s not our fault, but you still feel this regret and guilt.

KS: Yefim is not the only family member keeping secrets, as we find out in Nina’s story. Why did you choose to have multiple family members with secrets?

SV: So I think every family everywhere has secrets from each other, right? That’s a given. But I feel like in a totalitarian society, the price of keeping secrets in a family is amplified to the nth degree, because these secrets are typically heavier. There are five points of view in the story, and they all carry secrets. Some of them are much smaller than Yefim’s. But I wanted to explore that dynamic of keeping secrets while not perceiving that the other person has one as well.

KS: I love books with secrets.

SV: I am generally fascinated by secrets we keep ostensibly to protect those we love, but really to protect ourselves. And I feel like we all do this. We sidestep the truth because we don’t want to offend, or we don’t want ourselves to be perceived in certain ways by our mother or father or kid or whatever, so we omit things or straight up lie.

KS: While most of the book is from Yefim’s point of view, we also get glimpses into Nina’s thoughts as well as their children’s. How did telling this story from multiple points of view help shape what Yefim was hiding from his family?

SV: For me, it was very important to show not only what happens to the secret keeper, but how it was possible for people so close to the secret keeper to not see the secret. Not feel it. Like how do we keep ourselves blind, often on purpose, to what we don’t want to see? That is something that interests me a lot. The only way to explore that idea was to have multiple points of view, so we see him keeping secrets but we see everyone else missing it.

KS: This book was especially meaningful to me as someone with family in both Russia and Ukraine. I always knew my grandparents grew up with their own secrets, but your novel led me to reflect on the psychological implications of those secrets. What do you think has changed in 70 years and what do you think has stayed the same?

SV: I think the Russia Ukraine war has been a huge wake up call for Ukrainians because they’ve been forced to reexamine and understand their own identity. While for Russians, this war has had a dual effect. One part of Russian society has revolved back to what is very reminiscent of Soviet times in terms of giving up all self-determination to the state. While the other part of Russians, some who have left, are dealing with a new and very incredibly heavy sense of national shame and regret for letting their country get to where it is today. And similarly to Ukrainians, they must rethink what they thought they knew about their country.

KS: What is it like for you to write, edit, and release this novel during Russia’s war with Ukraine?

I’m interested in how we keep ourselves blind, often on purpose, to what we don’t want to see.

SV: I was editing the last chapter of my novel when Putin attacked Ukraine. And while I wrote the novel before the full-scale invasion, the war brought a lot more focus on Ukraine and Russia and their history, thereby making the release of my novel feel more important. It no longer feels like a book I wrote inspired by my family. It feels much more like a contribution to history in the making. I saw this as an important story before there was a full-scale war, but now it feels even more validating to bring this work forward because there are real life human costs.

KS: What has the reaction to your book been like from both your Russian and Ukrainian peers?

SV: So far, my early readers who are from the region have been really touched by the story. I feel like I wrote this book both to shine the light for the Western reader on this part of the 20th-century history, but I also wrote it for the people there. And it has been really gratifying to see how closely they are taking it to heart.

KS: Are you like nervous at all? Because you identify as both Russian and Ukrainian?

SV: Yes, I have been very nervous about how people from there will react given how sensitive everyone is and how much misinformation there is. So far, it’s been nothing but positive and people who have read it are very eager to share the book with their relatives from there. Another thing I’m nervous about is how will Germans take this book. So far, I have one German friend who has just finished reading it and she said she can’t wait to give it to all of her relatives in Germany because, and I quote, “so much has been forgotten and it’s a very important book for them to read”. And that feels incredible to hear.

KS: If you could talk to your grandfather today, what would you ask him?

SV: Why couldn’t you forgive yourself for what wasn’t your fault?