interviews

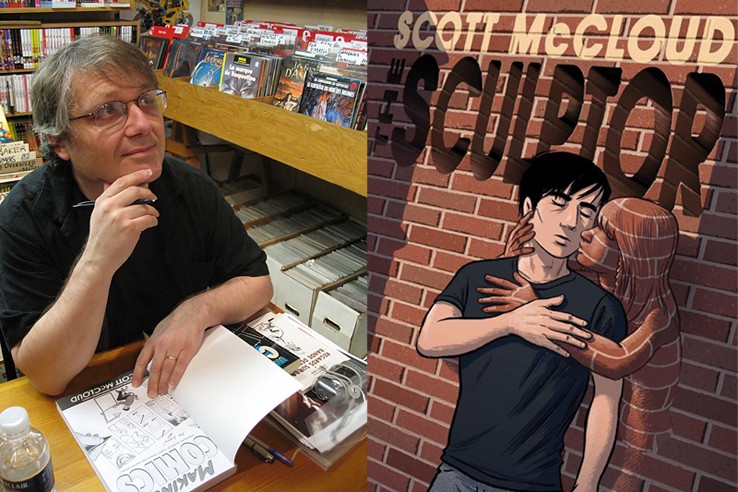

INTERVIEW: Scott McCloud, author of The Sculptor

When Scott McCloud published Understanding Comics more than twenty years ago, appreciating graphic novels was not a signifier of cultural capital, and comic books were still actually published for children. And Calvin and Hobbes was still carried in most American newspapers. Now comics are deeply ingrained in the American academic canon and they are no longer shelved as ‘Humor’ at the local Barnes and Noble. More than any individual — including Art Spiegelman, Alison Bechdel, Will Eisner, and Marjane Satrapi — we have McCloud to thank for the medium’s broader esteem.

Now, after decades at the forefront of the critical discussion, McCloud is a debut graphic novelist, with the publication of his 500-page opus, The Sculptor. This book follows the story of a young sculptor, named David Smith (not that David Smith), who makes a deal with the devil in hopes of achieving artistic success. McCloud uses a clean and flowing approach that encourages us more to experience this story than to pay attention to its individual pages and isolated moments. We spoke over the phone recently to discuss the origins of The Sculptor, the critical demands of making comics, and where McCloud sees his career going next.

John Dermot Woods: Is The Sculptor the first long work of fiction that you’ve created since you published Understanding Comics in 1994?

Scott McCloud: Yes, but I’d have to put an asterisk there because I am responsible for a widely hated graphic novella called The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln which people still make fun of me for. It was a clumsily computer-generated comic that I did in 2000. It was sort of a kids’ comic, sort of not. But everybody hated it. That thing was only about a hundred pages long. In my mind, you have split page counts in half with comics. If you’re doing a 500-page book, like I just have, then, in terms of narrative density, that’s probably equivalent to a 250-page novel. To me, it’s not really a graphic novel until you’re up around the 200–250 mark. This is the first time that I’ve ever really ran at the idea. You can collect a lot of my early comics together in a big fat book, as we did recently. But this is the first time that I ever sat down to write something self-contained and substantial to bring with you to Cape Cod on a long weekend in a rented cabin.

JDW: I think someone said that a graphic novel is a project that takes a lifetime to create and fifteen minutes to read.

SM: (laughs) Chris Ware is very eloquent about the tortures of creating these “slow motion picture stories.” Friends grow and have children, and their children have children, as you’re working on these things. But, I don’t mind, because those five years were very productive and rich for me. I know that, if it’s done right, then you will feel in the end that you get that time back, because it pays back time and dividends for the times that people are able to read and reread it.

JDW: So this book took five years to complete?

SM: The idea had been kicking around for a few decades, quite literally. But the active work on the book took five years. Originally it was supposed to take me only three but I had a very charitable editor who thought that I could do a better job if I had a little bit more breathing room, and I hope that he was right.

JDW: Looking at how substantial the work in The Sculptor is and how particularly you executed it, I would’ve expected that it took longer than five years.

That’s wonderful to hear. If I had a new book out that was 250-pages long and took me two and a half years, nobody would care. That wouldn’t be remarkable at all.

JDW: How was your experience different during these five years creating a work of fiction rather than a work of critical analysis? Was it a different experience for you on a day-to-day basis, sitting down at the table (or screen, in your case) to work?

SM: It was consciously different. From the very beginning I set out to impersonate my opposite number. The theorist, the guy who wrote all those books about comics, wanted you to stop and think about each and every panel, wanted to point to exactly what was happening on the page. With The Sculptor, I wanted to create something utterly transparent, the kind of storytelling that pulls you in and within a few pages vanishes. The mode of presentation is invisible and the only things left are human beings, situations, the themes. I wanted people to fall into this book, be propelled from page to page all the way to the end and come out blinking in the sunlight. I didn’t want them to even know they were reading the comic at all.

JDW: That’s certainly the experience I had with the way that you constructed your pages in The Sculptor. Structurally, it’s remarkable how fluid your pages are. I didn’t actually consider them in comparison to your other work. But now I’m back in my office, surrounded by your other books, preparing to start my semester teaching tomorrow, and looking at the books beside each other. The difference is striking.

In terms of your critical works, one of the ideas that you address in Understanding Comics that consistently excites my students is the comparison of comics to other media and how that can be limiting, but ultimately useful. Comparing comics to film can be particularly compelling. And this applies to The Sculptor. I found this book to be particularly cinematic. But not in a visual way, not in the way you discuss in Understanding Comics. The narrative tropes in The Sculptor feel particularly cinematic. There is a certain sense of quickness, as Calvino would call it, in this narrative. Were you conscious of film at all when you were creating this story?

SM: Very much so. In some respects, when a comic has a cinematic feel to it, in the telling, that is because of a direct influence. Will Eisner, for instance, was strongly influenced by film when he was doing his comic The Spirit in the 1940s, which, in turn, influenced a lot of other comics after that. You can see direct influences from film. But sometimes you can get that cinematic sensation simply because comics have successfully created that narrative momentum and verisimilitude that we associate with film. Film, when done right, is simply a seamless waking dream. And, if comics can achieve that same effect, then they can seek to arrive at the same destination having taken a different route. Now there are some things in comics storytelling that can take you away from that: if there’s a lot of narration, for example, a lot of captions, if it’s obsessed with the surface of the drawings, if it wants you to forever notice the drawings. All of these things can keep it nailed to the page. But I did not want it to be nailed to the page. I wanted you to be looking through windows into an actual world.

It’s a very cinematic book in other ways too, because I was trying to be a more intuitive storyteller and to put story first. I was thinking more like those people for whom the medium was not the point. I find a lot of people like my friend Kurt Busiek or Neil Gaiman are happy if they get the opportunity to go into other media. I can tell you for sure that my old friend Kurt, given the opportunity, would not balk at writing a TV show or a movie, because he’s a storyteller, first and foremost. It’s his relationship with his audience that matters.

It’s also appropriate and symbolic because my wife, who figures prominently in here as an inspiration for one of the two main characters, and I have a long-standing relationship with the movies. We met at the movies in college. We go to movies compulsively. All the time.

JDW: As cartoonists, I think we often fear the comparison to film and try to avoid it, and sometimes we don’t even admit the relationship exists. So I appreciate your engagement with film. What I think a lot of people are rediscovering right now is narrative. For instance, I am currently scripting a comic for a friend who will draw it. And this is something I said that I’d never do, as it seems so unnatural. But we’ve found a particular working method, and it’s an exciting way to create. Over time, it seems that we can rediscover comics through other media.

SM: Yes, and it’s good to exercise those muscles in isolation. Even I wrote scripts for other people when I did a children’s Superman comic for DC. I was writing scripts for others to draw. But, for me, that forced me to engage with story in isolation, without being able to lean on my skills as an artist to bail me out. And it’s good to let go, once in a while, to just treat something as an exercise in craft. If it doesn’t quite come out the way that you want it to visually, just say it’s all right. Now it’s somebody else’s art.

JDW: The Sculptor is certainly a book that looks at other people’s art. The book is, in certain ways, a meta-criticism of the world of art criticism. It involves a sculptor who struggles with being aware of the critics and how he deals with that pressure. As a cartoonist yourself, I wondered, is this book, in any way, a response to the criticism that surrounds comics specifically?

For a lot of artists, there has to be something, some kind of universal art judge hanging over us, who knows that there’s a difference between The Big Bang Theory and Finnegan’s Wake.

SM: I don’t know that it is a response to the criticism surrounding comics as an art form. And, I think only very tangentially was it a response to my encounter with actual critics. It was very important that the one capital ‘C’ critic who figures in this story, the one fellow who seems to be straight out of central casting, a slightly villainous, nasty nemesis, is on some level right. And David is right to have certain doubts, because he sees himself as flawed in ways that he doesn’t know how to correct. Also, at the heart of it, is this notion that there can be a verdict. It’s not so much that people’s verdict of you is negative or positive. It’s more the faith we have — even if we have no religious faith — that there’s some arbiter of quality, arbiter of artistic worth, which is a quasi-religious belief. It’s very hard for some people to adjust to the notion that if people like it, it’s considered good, and if people don’t, it’s considered bad, and that’s the end. That’s a very horrifying idea. For a lot of artists, there has to be something, some kind of universal art judge hanging over us, who knows that there’s a difference between The Big Bang Theory and Finnegan’s Wake.

JDW: As we read The Sculptor, we expect that David will overcome the big, bad critic. Each time it seems that David is about to realize his own genius, but as judgment is revealed, and his own self-reflection is revealed, his work is always brought down to earth again. Even his ultimate gesture can still fall to criticism.

SM: And to time. Anything that he creates during the course of this story can fall over time, can topple, can crumble.

JDW: When David presents his work, I was prepared that the critics and those “in the know” would either declare it a work of genius, or ignorantly dismiss it as trash. Instead, they tell him he’s got something, but he’s got to work on it. I thought it was interesting that critical opinion was presented so reasonably within the story.

SM: Right, his work was mess, just a big colossal train wreck of ideas that don’t quite add up. What his friend Oliver tells him is that people in the art world are looking for a single coherent vision. While I wouldn’t even begin to present myself as any kind of expert on the art world, I don’t think that’s an unreasonable way to put it. If you can do a,b,c,d,e,f,g, and h, it won’t really get you far, in any kind of artistic endeavor. They want you to pick one and go with it.

JDW: People want to be able to identify this thing that you do.

SM: Because they want the work to be an extension of you. David was unable to pull that out. And it crushes him, this idea: he gave his all to his art and it didn’t even occur to him that the verdict might not go the way that he thought it would.

By the way, if he had made masterpieces, from a storytelling point of view, I would not have shown you them. David only makes one artwork that’s embraced by one or more people in the art world, and we never actually see it. Because I don’t consider myself talented enough or don’t think that I have an acute enough eye to create something that could credibly be considered worthy of the attention of that world. In fact, it could be that no one could create such a thing on the comics page.

JDW: As I read The Sculptor, I was conscious of the struggle you must have had portraying art on the page. It was a similar challenge, I thought, to what Rachel Kushner had to face writing her novel The Flamethrowers that portrayed the life and work of downtown New York City artists in the 1970s. The difference is, Kushner had to describe visual work verbally. You had to portray visual work visually. Kushner said that she drew from the historical and contemporary art worlds for inspiration. Were you inspired by any specific artworks when you conceived of the art portrayed in The Sculptor?

SM: Sure. I’ve been looking at art all my life. It’s not my vocation, but each time I travel I always try to find local museums, especially modern art museums, because I enjoy looking at the stuff, being immersed in it. For me, in some ways, it’s all environmental sculpture. It’s being surrounded by it that I find compelling. I like that way that it transforms my environment, even if that’s not the purpose of the work, even if that’s not its conception. I happen to be surrounded by five different sculptures, by five different sculptors, and that has transformed the world I live in temporarily and I find that really intoxicating. I like it.

I have a few sculptors that I’ve always admired, like, strangely enough, David Smith, who shares a name with my young sculptor in the book. That is a real curse in the art world, because there is already a very famous dead sculptor named David Smith. I happen to like his early work. I like Louise Nevelson. I like Lee Bontecou, whose retrospective I only got to see pretty recently. I didn’t know much about her before this. I like Serra. But, I’m no expert in sculpture by any means. David’s work comes as much from my imagination as it does from a survey of the work currently favored by the art world. This is why I only felt comfortable drawing the work of someone who remains an outsider, who cannot enter that world, who is not able ever again to penetrate that fortress. That work I could draw. I could draw work that could be rejected by a gallery. I don’t think that I could have drawn work that would have been accepted.

JDW: You made the choice that your David Smith would have the super power to be able to meld things and to sculpt and to make art. Considering the fact that you’ve made Superman books, and the you’re the guy who wrote Understanding Comics, it’s interesting that your first graphic novel is about a character that has super powers but is clearly not a genre book. Is that a challenge you gave yourself?

It’s a cruel accident of history that I’ve spent the last twenty years on the stump trying to convince anyone who would listen that comics are about more than power fantasies and super heroes.

SM: It’s a cruel accident of history that I’ve spent the last twenty years on the stump trying to convince anyone who would listen that comics are about more than power fantasies and super heroes. But, I’ve had this story in the back of my mind for decades. It came from the days when I still had one foot in that world. It worried me. I didn’t like the idea that it could be seen as a serious super hero comic, which is pretty much the prog rock of our world. There’s no more despised, middlebrow, awful thing to be working on than a serious super hero comic. Yet, in some ways, that is what it was. But, I think I found a way to redeem the story by acknowledging the fact that it came out of my own past, it came out of this American power fantasy landscape. In part, I did that because his power grows out of a childhood wish that my protagonist makes. As a kid he draws this homemade comic that has something like what he ends up inheriting from this supernatural Faustian bargain. This is also partially about my making peace with the fact that those power fantasies are part of the DNA of American comics culture. I think it’s healthy to acknowledge it and, rather than simply trying to banish it from our imagination, maybe we need to take a new look at it, come at it from another angle.

JDW: This is something I think about a lot. My students are far more knowledgeable of genre books than I am, and I’ve had to confront the fact that perhaps I’m denying my own, mostly pre-pubescent, relationship with super hero books.

SM: My friends and my editor encouraged me to do something. When I was first working on this book, I was more understated in the scenes in which he is using his power. I had to come out of the closet as someone who enjoyed those books very much at one time in his life and try to rediscover some of that joy and exuberance because that’s part of what made this a compelling story for me when I was 24. And I had to acknowledge that and accept that at the age of 54.

JDW: I appreciated the moment when Uncle Harry addresses this issue directly. He tells David, “And don’t go out fighting crime.”

SM: I have to give credit to Repo Man. The structure of that conversation was definitely influenced by Harry Dean Stanton telling Emilio Estevez that he doesn’t want any “commies” in his car. And then there’s a pause and he says, “And no Christians, either.” I always thought that was such a beautiful line. I like the way it comes out of left field.

JDW: This book did not feel like a “serious super hero comic.” It didn’t feel like an attempt to burn down the past, like a DC Vertigo book. It didn’t feel like a book that says, “Here are your super heroes, but they’re darker and more real and have sexual dysfunction.”

SM: Thank you. It’s a great comfort to hear you say that.

JDW: Your book Reinventing Comics came out very early in the conversation about digital comics. But, now, more than a decade later, I think that most of the questions you asked are still unanswered.

SM: I would tend to agree with you. I think many of those questions are still hanging out there.

JDW: Did you always conceive of The Sculptor as a print book? (I ask this because I received the book as a digital and a print galley, and I read it using both media.)

SM: It always felt like a print book to me. In a way, I didn’t have a choice because we don’t yet have a method by which you can spend five years serializing a graphic novel on the web. There doesn’t seem to be a reliable model yet for long-form serious work of that sort without a punch line at the end. So, in a sense, the choice was taken away from me. I was comfortable with this being a print book. I conceived of this at a time when that was the only way to go anyway. And I felt that this might be my last chance to engage with the limitations of print in a way that was constructive. I talked about those limitations and tried to transcend them online, and I felt I was better able to come back to print with the knowledge of those limitations, especially the edge of the page, which I think is something that very few print cartoonists think about, the fact that every time you choose the size and shape of panel one you are restricting the size and shape of panel two. This does not have to be true online, when you’re treating the screen as a window. Within that limitation, it presents interesting challenges, and I think I approached that in a more conscious way than I ever have before.

JDW: You really did challenge yourself with these layouts, using what Ivan Brunetti would call the ‘hierarchical grid.’ On every turn, you’re reinventing the page.

SM: If you look at the side of the book, though, you’ll see stripes, because the whole book is constructed on a three tier, equal division grid, but with a lot of bleeds. Underneath it is a hidden structure. It’s not obvious when you’re reading, but it is there. The bleeds make it seem more organic and unpredictable.

JDW: I like to show my students Jaime Hernandez’s work, because he often does something similar. Sometimes he’ll give himself two different grids to work off of, and he seems to shift them as the tone of his story shifts.

SM: I do that too. I got to audit Art Spiegelman’s class when I was living in New York and I was working in DC’s production department. I remember he was talking about Kurtzman’s war comics and the ‘ratatatatat’ pacing of the increasingly narrow panels.

JDW: You edited this year’s Best American Comics. That gives you a pretty singular insight into what’s going on in American comics at this moment. Someone asked me to write a best of 2014 list and I realized that I only read two comics published in 2014.

SM: I hope This One Summer by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki was one of them. It’s a really gorgeous book. Check it out, if you haven’t.

JDW: I will. It’s been more than two decades since Understanding Comics was first published, and you just edited the Best American. We can confidently say that your book has influenced the way a lot of people not just understand comics, but create comics. How do you think the field of American comics has changed most notably in those two decades?

SM: In the last two decades, the first headline is diversity of content and diversity of form. Twenty years ago, in 1995, the web was only just beginning to take hold in American culture. The manga influx hadn’t gotten going in a big way. And the graphic novel form was still basically Maus, Watchmen, and Dark Knight. That was it. And Will Eisner’s stuff. It wasn’t so much a genre but a promise that was being held out. Any one of those things would’ve revolutionized the medium, but to have them all happen at once created a hurricane of diversity. And diversity is healthy. By reducing the inbreeding in comics, by broadening by a factor of ten our content footprint, and by finally beginning to correct the gender imbalance, I think comics are healthier than ever. And we’re beginning to increase that small shelf of works for the ages. This notion of a cannon is starting to seem increasingly less ridiculous as time goes on. There are books that we can begin to rely on to continue to reward reading and rereading. Not all of them are famous. I’m a great admirer of a book called Market Day by James Sturm. Sturm is moderately well known in comics. But he’s certainly not as internationally known as Marjane Satrapi. But I think Market Day is a bulletproof graphic novel that I hope everyone will try. It is a simple book but it is a master class in how to tell a story. And it’s a story I can’t get out of my head. It’s very good.

JDW: Do you have plans for another work of fiction? Are you planning a follow-up to Making Comics? What are you working on?

SM: I would love to work on another work of fiction, but the first order of business, other than taking some time off and traveling with my wife, is to work on another nonfiction book. This time it will be about the fundamental principles of visual education and visual communication. I would like to see if I can discern many of the fundamental, good practice principles of communicating with pictures. I look at it as an Elements of Style for visual communications.

JDW: That would be an incredible resource.

SM: Well, I can only disappoint!

JW: Thanks for taking the time to talk, Scott.

SM: It’s a pleasure, John.

Author photograph courtesy of Simon Law