Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: Merry Christmas, Charles Dickens

Each month in the Literary Artifacts space, writer Kristopher Jansma writes about his encounters with rare books, writerly memorabilia, and other treasures in New York City and around the world, hoping to discover how the internet age is changing the face of literature as we know it.

Without Charles Dickens, Christmas today might well be a relatively minor holiday with no gift-giving, no large family-gatherings for turkey dinners, no Bing Crosby songs on the radio…perhaps even no Macy’s Santa, Swarovski-Crystal-topped tree, or kick-lining Rockettes. All this and more we owe to a slim stack of messy manuscript pages that came to be known as A Christmas Carol, currently on display at the Morgan Library in midtown Manhattan.

In the early 19th century when Dickens was a boy, Christmas was barely celebrated at all. In his introduction to A Christmas Carol, Professor Richard Michael Kelly explains that farther back, in medieval times, peasants and lords alike celebrated Christmas with a twelve-day rager, glomming the Nativity onto the pagan feasts of Saturnalia and the Winter Solstice to create a super-holiday full of carol singing, gift-giving, raucous game-playing, the burning of Yule logs, and a whole hell of a lot of drinking. But by the 17th century, Puritans in England and America had all but outlawed these sinful celebrations and Christmas had dwindled into a relatively-minor holiday. It was the publication of A Christmas Carol that prompted the widespread public celebration of the holiday we know today. Yes, that’s right. Without Dickens, buzzkill-Christmas might have persisted to this very day, with no Black Friday pepper-spraying, no insane mega-watt home decorations, no terrifying Target 2-Day Sale commercials, no Paula Deen “Mama’s Eggnog” (it starts with a pint of heavy cream…), no ironically ugly Christmas sweaters… well, you get the picture.

According to Professor Kelly, a few bits of Christmas nostalgia had begun to emerge by the early 1830s: a collection of old Christmas Carols had been published and Prince Albert had adopted the German tradition of decorating a tree with lights, but the average Londoner did not make much of the occasion. Similarly, in America, populist President Andrew Jackson celebrated the holiday with a lavish party where orphans from the local asylums had snowball fights in the East Room of the White House, but for the average Joe, Christmas came and went without so much as a stocking hung by the chimney with care.

It was around this time that Charles Dickens was first coming up as a journalist. The young Dickens had been well-educated until the age of 12, when his father was sent to debtor’s prison and Charles had to paste labels on blacking containers for six shillings a week. By 1833, at the age of 21, Dickens was crisscrossing England to report on electoral campaigns. The Morgan Library’s Charles Dickens at 200 exhibit has one of his portable inkpots on display, a nifty gadget which allowed him to take notes on the road. He recorded Lord John Russell’s 1833 nomination speech “in the midst of a lively fight maintained by all the vagabonds in that division of the country, and under such pelting rain, that I remember two good-natured colleagues… held a pocket handkerchief over my notebook.” Dickens worked tirelessly, every day from 9 AM to 2 PM, producing between 6–12 pages per day — a pace that he would maintain throughout his career. He eventually gathered his articles into a collection called Sketches by Boz (Dickens’s middle name and pseudonym) and this led to his first serialized novel, The Pickwick Papers. The Morgan also has this on display: a truly remarkable bundle of little paper volumes that look a bit like homemade literary magazines, with hand-drawn covers and sewn binding. At 25 years old, he was writing around 19,000 words a month (30 pages or more) to complete new sections of Oliver Twist for about £14, plus the promise of £150 upon completion. His subsequent novel, Nicholas Nickleby, sold 50,000 copies on its first day. In 1842, at the age of 30, he made his first voyage to America, where he gave lectures to readers and encouraged local publishers to get serious about copyright laws (which he considered lax). Dickens wrote home, “They cheer me in the Theatres; in the streets; within doors; and without.” He also found time to tour Wall Street and the Tombs prison before stopping off at the White House to condemn the practice of slavery to then-President Tyler.

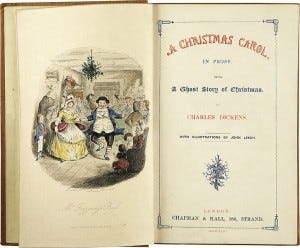

All this to say that Dickens was already a bit of an international literary superstar in December of 1843, when he first began work on A Christmas Carol. According to letters on display at the Morgan Library, Dickens wrote the holiday novella in just six weeks. Dickens was so focused that, according to a letter displayed next to the manuscript, he had to ask his friend Thomas Mitton for a loan to help pay the bills he’d been neglecting while writing. The original manuscript is covered in insertions and cross-outs, made on-the-fly as he progressed. Anyone curious can see a very nicely-done digital facsimile on the Morgan’s website. The gift shop sells replicas, which include scans of the original manuscript pages along with the printed text and illustrations. You can also download an eBook version for free from Project Gutenberg! Looking at the manuscript one can easily see that, as the Morgan’s commentary puts it, “the pace of writing and revision, apparently contiguous, is urgent, rapid, and boldly confident.” This is the very same handwritten manuscript that was sent directly to the printers at Chapman & Hall early that December. They somehow deciphered Dickens’s chicken-scratch and printed up an initial run of 6,000 copies — every single one of which would be sold by Christmas Eve.

It was an instant classic throughout London and soon all of England. Readers were swept up in the simple tale of Ebenezer Scrooge, a miserly money-man who is taken on a ghostly tour of his life which reminds him of the values of family and generosity. Readings and performances of A Christmas Carol immediately became a seasonal tradition, and historians believe that the lively, nostalgic scene at Mister Fezziwig’s Ball (in Scrooge’s innocent youth) and the two concluding Christmas feasts, full of roasted turkeys and plum pudding, are what resurrected the Medieval vision of a celebratory Christmas, holy not for its piety or solemnity, but for its lively gathering of family, charitable generosity, and tidings of goodwill towards our fellow men.

A Christmas Carol was lauded by the day’s literary critics like Thomas Hood and William Makepeace Thackeray, who declared the book “a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness.” Dickens soon began to receive letters from readers far and wide who described how they kept the Carol on special display by the hearth and read it aloud each year at Christmastime. Other critics noted that the book not only pleased readers but also seemed to have a stunning impact on their behavior. In the spring of 1844, charitable-giving had increased all around Britain, a trend attributed directly to Dickens by magazines of the day. Robert Louis Stevenson and Thomas Carlyle each wrote effusively of the effect that A Christmas Carol had on their own generosity that season. An American businessman was apparently so moved by the book that he closed his factory down and sent each of his employees a turkey, and after The Queen of Norway read A Christmas Carol, she sent gifts to the crippled kids of London, “With Tiny Tim’s Love.”

In short, the influence of A Christmas Carol is not to be underestimated. Though Christmases in Eastern England were rarely snowy, Dickens’s backdrop of a blizzardy London in his Carol stuck with readers and helped create our expectations of a “White Christmas.” Today, we’re likely to call anyone who is not in the Christmas spirit a “Scrooge” and give them a sarcastic “Bah Humbug!” Most of us know that we owe these phrases to Dickens, but hardly anyone realizes that he also popularized the greeting of “Merry Christmas.” Scrooge’s visiting nephew says it to his uncle in the very first chapter. In all his curmudgeonly glory, Scrooge replies “’Merry Christmas’! What right have you to be merry? […] every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart. He should!” The saying may have become somewhat ingrained in readers’ minds after that.

This might be news to the “Billboard Ladies” seen recently on Fox & Friends, 168 Christmases later, who (in an effort to displace the “happy holidays” greeting) have erected billboards in Ohio saying “I miss hearing you say ‘Merry Christmas’ — Jesus.” In fact there are as few mentions of Merry Christmas in the teachings of Jesus as there are mentions of Christ in A Christmas Carol. Though Dickens was a member of the Anglican Church, there is not a single reference to Christ, Jesus, or the Nativity. God, however, does garner twelve mentions, including Tiny Tim’s famous “God bless us every one!” which is repeated as the final line of the book. Biographers believe that Dickens was considering a switch to Unitarianism around this time, later deciding to remain an Anglican when the Church became more moderate.

In his introduction to the Oxford World Classics “A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books”, Dr. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, describes the Carol as “an alternative Christmas story to its more obviously religious rival, in which the three wise men are replaced by three instructive spirits, and the pilgrimage to a child in a manger is replaced by a visit to the house of Tiny Tim.”

Though the ghosts who visit Scrooge make references to their afterlives, they never discuss heaven or hell. Scrooge is not haunted by the vision of eternal damnation, but rather of being unloved and forgotten in death. This is when Scrooge promises to mend his ways, pledging not to be a good Christian or to heed the word of God, but rather to embody the generous holiday spirit by swearing to “honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.” While these lessons are certainly in keeping with the Christian ethos, Dickens emphasizes Christmas as a kind of good-unto-itself. Perhaps this more secular approach is what helped to revive the holiday in the imaginations of Carol’s first readers. Most certainly it seems to be a reason that today its influence has spread to be nearly-universal.

According to the notes at the Morgan Library, within a few weeks of publication, A Christmas Carol had been adapted into 8 separate theatrical productions, though Dickens had only authorized one, by director Edward Stirling. The others, which he angrily called “piracies”, were crucial, however, in spreading his tale and his name to those who could not read or could not afford copies of the book, which reviewers at the time did grumble were too expensive.

Today, of course, one can hardly change a channel in December without running into A Christmas Carol in one of its many forms. It has been adapted for the stage countless times since those initial performances. There have been at least 22 separate film versions going back as far as 1901, and 23 on television since 1944. Before that there were 12 separate radio versions, and there have been at least three operas. Scrooge has been played by everyone from Marcel Marceau (miming on the BBC), George C. Scott, Patrick Stewart, Michael Cain, Bill Murray, Vanessa Williams (as “Ebony Scrooge” in 2000’s “A Diva’s Christmas Carol”), Kelsey Grammar, and a CGI Jim Carrey. The tale has been cutely-packaged for children since the days of Mr. Magoo, with Ebenezer reincarnated among The Flintstones, The Jetsons, Barbie & Friends, The Smurfs, the Sesame Street Gang, The Muppets, Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, and Doctor Who. This year, Housing Works Bookstore hosted their second-annual “What the Dickens?” Marathon, where literary superstars take turns reading the entire Carol aloud. And perhaps most awesomely of all, A Christmas Carol has been translated entirely into Klingon and performed in Minnesota and Chicago by the Commedia Beauregard.

It is hard to imagine, looking at the near-indecipherable manuscript at the Morgan, that Dickens’s simple story would have such a vibrant life, 168 years later, or that it could have sparked the revival of a major holiday, which for all its Black Friday lows, remains at its highs a time of peace, generosity, and goodwill. For all of Dickens’s concerns about “piracies” and lax American copyright laws, A Christmas Carol is today part of the public domain in every conceivable way. And because, at its heart, the tale of Scrooge is one of secular social justice, its message remains universally-accessible regardless of culture or creed. Scrooge is so basically-human that his story can move us even when he is animated, or from the Klingon planet Qo’noS. Scrooge hoped that a life rededicated to goodness might help him change the “shadows” shown to him by the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come — that his neglected grave might be someday cared for. Perhaps, in our way of perpetual literary reinvention, the grave of Mr. Scrooge is being tended to.

And what strange forms of Scrooge are Yet To Come? He certainly seems ripe for Occupy Wall Street, though I can only find one bizarre incident of an OWS Scrooge. Perhaps he’ll be embodied by James Spader on The Office, or Danny DeVito on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia? It seems nearly inevitable that there will be an Ebenezer Squidward on some future episode of SpongeBob SquarePants, or that Harrison Ford will someday don a top hat and grow muttonchops for a new blockbuster hit (just give Hollywood a few more years until the memory of Ghosts of Girlfriends Past wears off).

Whatever the case, the original Ebenezer will surely remain safe on the pages of A Christmas Carol, in the words of Charles Dickens, and in the better aspects of what has become a world-wide celebration of Christmas.

***

— Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in Manhattan. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards will be published by Viking Press in 2013. He has studied The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and has an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University. He is a full-time Lecturer at Manhattanville College and also teaches at SUNY Purchase. Recently, his short story “A Summer Wedding” won 2nd prize in The Blue Mesa Review’s 2011 Fiction Contest, judged by writer Lori Ostlund. His essays and fiction can also be found on The Millions, ASweetLife.org, The 322 Review, Opium Magazine, The Columbia Spectator, and The (Somewhat) Complete Works of Kristopher Jansma. You can also find him on Facebook.