Interviews

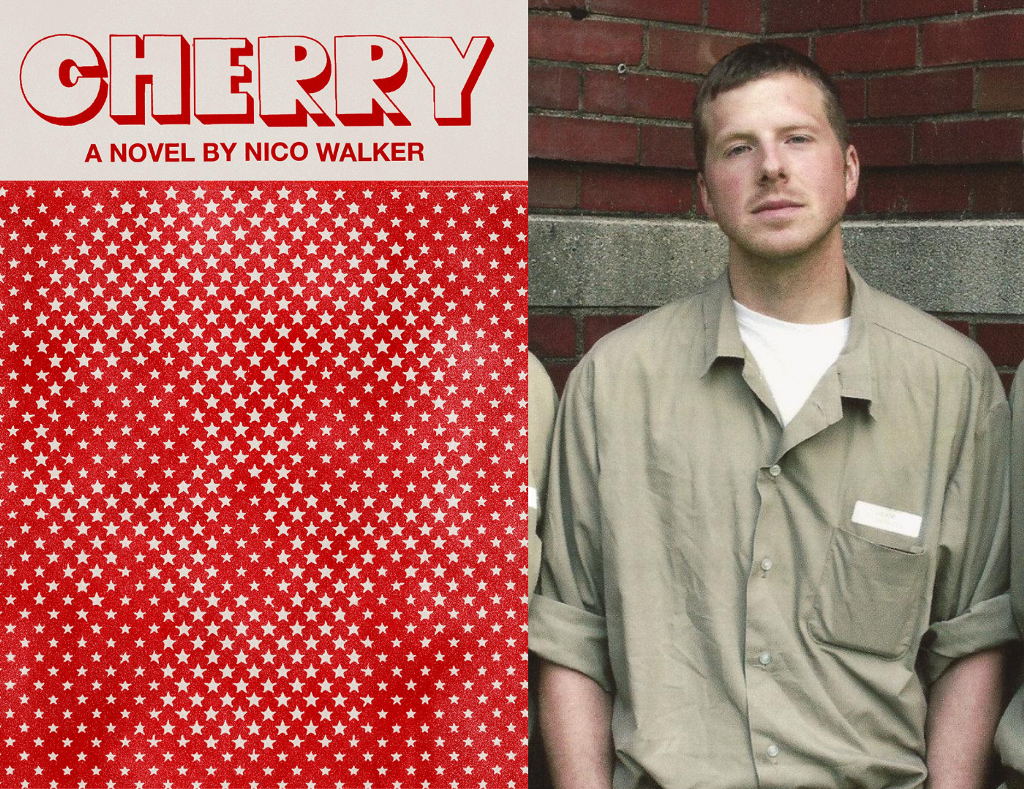

Meet Nico Walker: Iraq War Hero, Incarcerated Bank Robber, and Debut Novelist

The author of ‘Cherry’ on the challenges of writing a book in prison

Many debut novelists are churned out of the M.F.A mill, their manuscripts drafted on an MacBook Air in a hip coffee shop and then submitted online to a literary agency for an unpaid intern to discover in the slush pile. Nico Walker is not your typical debut novelist. For starters, he wrote his debut novel on a typewriter in a federal prison where he is serving an 11 year sentence. It’s safe to say that Walker will not be signing his novels at your local bookstore anytime soon.

Walker enlisted in the army at 19 and served as a U.S Army Medic in the Iraq War in 2005 and 2006. After his tour, he came back to America with medals for valor and post-traumatic stress disorder. He turned to drugs to self-medicate the lingering trauma of war and developed an addiction to heroin. To fund his addiction, Walker started robbing banks. When he was finally caught, he had stolen almost $40,000 in 10 bank heists.

Matthew Johnson, co-owner of Tyrant Books, discovered Walker from a long article in BuzzFeed and, after sending him a collection of Barry Hannah stories, struck up a friendship with him through letters. Johnson encouraged Walker to write a book about his life—and Cherry was born.

Walker writes with a wholly unique voice and structure that shows the possibilities of what can happen when we burn down the fences of what constitutes mainstream narrative. The strength of the narrator’s voice carries you between his youth, years in the army, drug use, and tumultuous relationships with the rapture of an old friend detailing your years apart.

Though the narrator’s story arc has the makings of an American epic, I found myself most rattled by the smaller moments in the novel, the quiet reflections on his lovers and friends, the cadence of a single sentence: “I tried to be good. But I was fucked up.” It was a pleasure to hear further from Nico over email about relationship failure, parallels of women and soldiers in combat, and the physicality of his writing.

Becca Schuh: For those who have yet to read Cherry, can you give a sense of the timeline of your life for the years the book covers?

Nico Walker: Yeah, it starts in late adolescence and it ends in arrested development.

BS: What were some of the challenges you faced in writing and editing a book from prison?

NW: Lots of challenges. It’s hard to tune things out here. I hope maybe I’m getting better at it than I have been before, otherwise it’s going to take me forever to finish the book I’m working on now. But there’s a lot of noise, a lot of stuff that gets in your head that you can’t avoid, you can’t ignore, and it makes you dumb just being around it, and it makes it hard to write. A lot of dudes in prison like to stand around and shout and just go blah blah blah all day, and it’s pretty terrible. Then the mail is slow; they have to go through everything. Mail goes out at certain times, so if you’re in a hurry you’re hit. No word processors obviously. But then that maybe works to my advantage with the way I write, which is all OCD, like all work no play OCD. Up, here we go, a dude at the email terminal next to me just starting screaming about something for some reason, and two minutes ago I had to stop typing so I could bend down and pick up a fireball candy that someone had tried to smash on the ground and that ended up going under my feet. These are good examples. I can’t wait to get out of prison. There were other things too. Like some days I couldn’t go type because we were locked down for fog or because the guards’ radios blanked out or whatever.

A lot of dudes in prison like to stand around and shout and just go blah blah blah all day, and it’s pretty terrible. I can’t wait to get out of prison.

BS: Did you find the process of fictionalizing your past to be cathartic?

NW: The best thing was feeling like it was all over with when I was done. Of course I’ve still got to talk about it now. But hopefully once the book’s in paperback and the movie’s on DVD or Netflix or whatever, it’ll be over then and I won’t have to talk about it anymore.

BS: How does the public perception of the Iraq War conflict with your personal experience as a veteran?

NW: I don’t know too much about it. I’ve seen a couple parts of some movies and they definitely weren’t anything like Iraq as I knew it. But then I was only in one or two places and only for a little while, so I’m not an expert on the war.

BS: Can you talk about the challenges of war veterans facing PTSD, and how the resources (or lack thereof) misalign with the needs of veterans?

NW: I don’t know what anyone can do about PTSD. You can’t un-experience things. I got a letter from a woman with PTSD the other day and she put it well. She said, You can’t unsee things. Which is about right. And you just can’t un-know what you know. What you know about life. What you know about what’s out there. There’s definitely a disconnect between Americans who’ve been to places like Iraq or Afghanistan, or whatever places like that, and people who haven’t ever been to such places. So it’s hard to think of any way that the one can get much help from the other. Time is the best thing that can help someone who’s having problems like PTSD.

[My novel] starts in late adolescence and it ends in arrested development.

BS: In your novel, the narrator starts robbing banks because of his drug addiction. Having gone through addiction yourself, what is your current perspective on the opioid crisis in the Midwest?

NW: Of course I think it’s tragic that all these thousands of people are dying every year. It seems like everyone knows someone who’s died. I definitely don’t think more laws are what’s needed. I definitely don’t think more “drug therapy” will help anyone. I think it’s a cultural problem. I think it’s a spiritual problem. I think there are a lot of people coming up in America who don’t want anything to do with what our country is about, don’t want to be what our society demands that they be. People are lonely. People are not valued. They find a quick way to feel good. Unfortunately it often kills them. Probably something should be done to make pharmaceutical grade opioids, like dilaudid, more easily available, so as to steer people away from the street drugs that are killing tens of thousands; just for a while anyway, while we work on solving the problem of why it is that people have this self-destructive desire to shoot dope.

People are lonely. People are not valued. They find a quick way to feel good. Unfortunately it often kills them.

BS: Your writing voice feels very natural — is this how words flow in your brain, or did you work to cultivate the voice of the narrator?

NW: The word order being out of the ordinary is something that comes naturally to me. Usually it’s something that I do that makes me sound dumb when I talk. But I noticed it and then I tried to develop it some and make it into something useful. Cadence or the rhythm of the sentences when I read them out loud is real important to me, maybe because I’m some kind of narcissist or something when it comes to the sound of my voice. Who knows. But I wanted to get it right, and so I tried a lot of things out for that, trying to get things to flow nicely.

BS: You portray several relationships where the characters have trouble figuring out their partners wants or needs. What inspired this focus?

NW: I was inspired by my own failings in my own personal life. The more distance there was between me and relationships I’d been in in the past, the more I’d blush about how selfish and dense I could be. I hope I’ve grown out of that some.

BS: “I tried to be good. But I was fucked up.” This line felt very simple and true to me. It also felt relatable do you think it’s a universal sentiment?

NW: Yeah, I think it’s true. I believe that most people, not all but most, who get into trouble get into it with the best intentions. For instance the narrator in Cherry, he creates a situation in his relationship with Emily wherein no one’s going to win. He knows that Emily’s heart is not a hundred percent in it and he’s only hoping that this will change for the better and that things will work out because of what will be there after the fact. He counts on things that aren’t true because he wants to believe in them.

9 Stories About Different Kinds of Prisons

BS: You portray a very visceral physicality with regard to injuries — how was the experience of writing such graphic and intense descriptions of wounded bodies?

NW: I didn’t like it. But it was necessary, I thought, for the book. I don’t get off on violence. There are books wherein violence is used for entertainment and I think that shit is stupid. I have a theory that books like that are usually written by soft motherfuckers, but this is neither here nor there. I’m not one for gore for gore’s sake. But I was just trying to show something for what it was like, and I thought it was important to do it that way.