Reading Lists

7 Books About Escaping Religious Fundamentalism

Meghan MacLean Weir recommends novels and memoirs that break free from the confines of oppressive religion

It wasn’t until the Episcopal Church ordained its first woman bishop in 1989 that I realized all the other bishops in our church, past and present, were men. I remember standing in our kitchen holding the newspaper clipping with Barbara Harris’s photo in my hand. I remember learning about the death threats and overhearing that a faction of the Church had decided to splinter off to protest her ordination. It was horrible. But what was worse, in my mind, was that the Church I loved and that I thought loved me, the Church for which my own father worked as a priest, had condoned a status quo equivalent to the sort of discrimination I thought it stood against. I was ten years old.

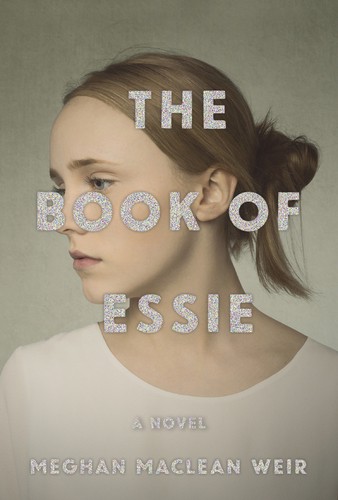

This feeling of awakening and betrayal is central to my debut novel, The Book of Essie, in which seventeen-year-old Esther Hicks is forced to question the authority of her own parents and her father’s cChurch when she discovers she is pregnant. The stakes are high for Essie, the star of her family’s reality show, but they may be even higher for her family, whose entire media empire would be threatened if the truth about Essie’s pregnancy became known.

In writing The Book of Essie, I drew from my own reading of other stories in which characters struggle to express themselves within the confines of a fundamentalist religion, some of whom find it necessary to break free. Here are a few favorites.

Disobedience by Naomi Alderman

The author is currently receiving accolades for her best-selling and timely novel The Power, but her debut (newly adapted into a movie) is equally lovely. In it, Ronit Krushka narrates her return to London from New York following the death of her father, an Orthodox Jewish rabbi. Prior to her moving away, Ronit had a brief and forbidden affair with her friend Esti, who is now married to Dovid, Ronit’s cousin and her father’s heir apparent at the synagogue. Ronit must negotiate these relationships and their complicated history, while at the same time learning how to grieve a father from whom she had been so long estranged.

‘The Power’ Is the Perfect Book for the #MeToo Movement

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

In this groundbreaking tale, the narrator is referred to only as Offred, her own individuality having been forcibly supplanted by her role as handmaid to the commander, Fred, whose name she assumes for the duration of her assignment. We learn that the Republic of Gilead was established after a religious revolution in the former United States and that fertile women are scarce. To combat low birth rates, these women are assigned to high-level government officials, a form of sex slavery rationalized by its Biblical origins. Offred’s ordeal is horrific, but it is also based, according to the author, on historical precedent. In addition to being adapted into an award-winning Hulu series, the novel is sadly more relevant than ever.

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

This classic, frequently taught in schools, is the story of Hester Prynne, who is shamed for an “illegitimate” pregnancy in 17th century Puritan Massachusetts, an area I call home. When she refuses to name her lover, Hester’s judgment is decided jointly by government and church officials and they consider putting her to death. Ultimately, in a sentence considered merciful, Hester is instead punished by being forced onto the town’s scaffold for a period of public scorn. She is also forced to wear a scarlet A on her chest, marking her as an adulteress forever.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

The Price family — mother, father, and four daughters — travel as missionaries to a remote village in the Belgian Congo in the late 1950s. The novel is largely narrated by the Price girls, each of whom is impacted differently by the move itself and by their father’s fumbling attempts to deliver the local villagers from what he sees as Godlessness and ignorance. Kingsolver does an excellent job of dismantling Nathan Price’s white savior complex and leaves the reader with a richer understanding and respect for the region in which the story is set.

Lolita in Tehran by Azar Nafisi

In this haunting memoir, the author describes her own experiences after the Iranian Revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Nafisi, a professor of English literature, was teaching at the University of Tehran in 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini decreed that all women must adhere to the Islamic dress code, including compulsory head covering. Nafisi refused and was expelled from the university. She later adopts the mandatory dress and teaches elsewhere for many years. After resigning, she teaches privately in her home and her students read, among other works of western literature, Nabokov’s Lolita.

Vladimir Nabokov Taught Me How to Be a Feminist

Ruby by Cynthia Bond

Liberty Township is a small and isolated African American community in east Texas when the novel opens in 1974. Ephram, the late preacher’s son, lives with and is worried over by his sister, Celia, who aspires to a position of prominence in their church. Ruby, with whom Ephram played as a child, has returned from New York and is widely understood to be crazy, an assessment based on her tendency to walk naked through the streets. Ephram is drawn to Ruby and, through their touching and unconventional love story, the two are able to piece together her traumatic past. They are opposed, however, by their congregation, who prefer to ostracize Ruby rather than help her heal.

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

This graphic novel is a memoir set against the backdrop of the Iranian Revolution, which occurred when the author was ten. Satrapi recounts how schools became segregated by gender and girls were forced to wear veils. The revolution was followed by the Iran-Iraq War, during which a Scud missile destroyed a neighbor’s house and killed Satrapi’s friend. In the wake of this loss, she becomes more rebellious, even speaking out against the regime. Eventually, fearing that Satrapi could be arrested or even killed, her family decides to send her to Austria to complete her education. Persepolis 2 describes the author’s homecoming and young adulthood in Iran.