Books & Culture

Injury by Proxy: Why “The Handmaid’s Tale” Is So Painful to Watch

In our political moment, Hulu’s adaptation of the Margaret Atwood novel is all too real

I was telling a friend how I couldn’t stomach violence on TV lately. I recently had a baby — “had” being the most outrageous euphemism for labor — and since then I’ve found that I involuntarily imagine my child’s body in place of the characters, his body receiving whatever pain is inflicted on them. I have similarly begun to think of how these characters, these actors, and everyone around me in real life, are all someone’s baby, the product of every ounce of someone else’s resources. As one of my care providers put it, when you’re pregnant the baby takes all the best parts of everything you consume and leaves you with the dregs, its body too precious to go without. If you don’t drink enough water, the baby takes what it needs and you just don’t get any. As babies, we each did the same––our bodies were also precious. We don’t have a word for the specific and infinite preciousness of a body; my friend had just lost a family member, and like me he also couldn’t stand violence on TV, said it made him almost literally sick, that now it felt too real.

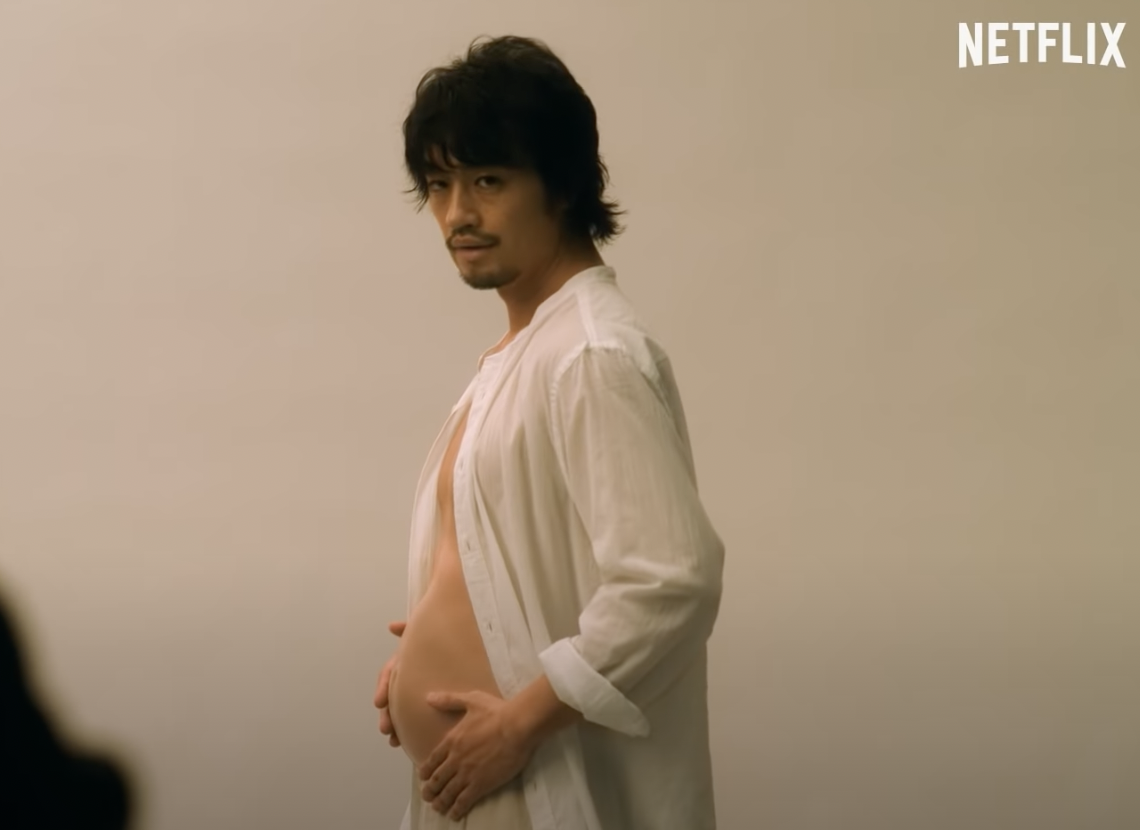

“Too real” is how it feels watching Alexis Bledel — as Ofglen, in Hulu’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale — forced to see her lover being hanged to death. Imagine your lover, the preciousness of their body. Can you bear the thought of something happening to it? Of death happening to it? Of seeing death happen to it? Too real is how it feels watching a handmaid in labor while the woman who owns her mimes labor beside her; how it feels to watch the handmaid deliver a baby and have that baby taken from her body, handed to the woman who owns both her and her baby, her labor. Too real is watching Ofglen wake after a clitoridectomy to be told it was irrelevant, to watch her realize what has been done to her unconscious, precious body.

These specific examples are all in Hulu’s extensions of Atwood’s 1986 classic, and don’t appear in the original text. But they are logical extensions. In the novel, widespread pollution has lead to a fertility crisis in the United States and beyond. This, combined with distant threats of terrorism, lays the groundwork for Gilead to take over, a totalitarian regime under which it becomes illegal for women to read, make money, or own property, and where a certain category of fertile women — called “handmaids” — are cast into reproductive servitude for rich men and their infertile wives. Atwood herself wrote the tale as a work of speculative fiction, because even if the world was imagined, the particular details were not. In an interview with PBS, Atwood admitted, “I made sure that every horrific detail in the book had happened somewhere at sometime.”

American slavery is one of the times and places to which Atwood refers, when women were institutionally owned, raped, and forced to bear children, only to have those children taken from them. In her piece “For black women, The Handmaid’s Tale’s dystopia is real — and telling,” Melayna Williams writes, “This, of course, was the reality for black women in America for hundreds of years, a period where it was nearly impossible for a woman to be born, live, and die of old age under a social system that deemed neither her body nor the fruit of her womb to be her own.” An American slave mother would have nine to ten babies on average (would “have”). How many slave mothers? How many women’s precious bodies? How many precious bodies were they forced to make from their own?

There is more than one way of forcing women to have babies — they don’t all resemble America’s history of slavery, or Atwood’s speculative Gilead. They may take the form of legislation restricting access to healthcare for women, or changing regulations so that clinics have to close, or changing access to insurance so that the poorest women’s options for contraception, education, and abortion are geographically or financially unattainable. As Mike Pence — who signed a law in 2016 that mandated funerals for fetuses — was made vice president, and as bills pass like Texas Senate Bill 25, which allows doctors to lie to patients about fetal abnormalities that might cause them to seek abortions, it seems as though we are headed farther and farther from the kind of country in which no women are forced to have babies — not black women, not poor women. No women.

Recently, at a talk she gave at BAM, the poet Claudia Rankine spoke about moral injury:

There’s a phrase called ‘moral injury.’ It’s a phrase they use for the military, and it’s when a soldier goes into war, goes into battle — and the things that they’re forced to do, the things that they’re forced to see, don’t line up with who they are as human beings. And so they experience a break in themselves. That’s what’s called the moral injury: their moral idea of how they are in the world has been broken, and they’ve become broken because of it.

Rankine was referring to our current moment, in this country, right now. When we see, since 2015, a “near tripling of anti-Muslim hate groups,” and see the president taking down the Spanish language-version of whitehouse.gov, as well as the pages on civil rights, climate change, and LBGTQ issues, we experience moral injury. When the president withholds federal dollars from sanctuary cities, and publishes lists solely of crimes committed by immigrants, we experience moral injury. When we see Donald Trump acting out old totalitarian ideas, as though The Handmaid’s Tale were a playbook — with Muslim bans and distant wars, the rolling back of environmental protections and the appointing of a global warming denier to head the EPA — we experience moral injury. When we see Vice President Mike Pence’s puritanical view of women being enshrined as law, it causes moral injury.

Moral injury is about bodies, how we treat each other’s bodies. Black bodies, Muslim bodies, LBGTQ bodies, immigrant bodies, Spanish-speaking bodies, women’s bodies, bodies that breathe air and drink water. We are implicated in what our president does; we live in the country he is the president of. We are represented by him to the world. We are participants in his reality, this reality TV star, whether in support or in protest, because it has become our reality now. And it is our moral injury when a body is hurt because of our country.

Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale makes its moral injuries feel real, more so even than Atwood’s novel, in part because it is so visceral. To watch Elisabeth Moss in the opening scene as she tries to escape through the woods with her daughter, to hear her black husband get shot, and hear her beg, “Please don’t take her, please don’t take her” as their daughter is ripped from her arms, to see her knocked unconscious by the state agents who’ve rendered them all powerless to do anything, is to feel morally injured. The performances of Moss, Bledel, and Samira Wiley (as Moss’s friend Moira) are key to the series’ visceral impact. In flashbacks to the gradual takeover of the nation by Gilead’s repressive regime, Moss and Wiley have a conversation that many Americans had, following our presidential election and what was promised to come. “They can’t just do this. They can’t,” the characters say. “We’re pulling together a march for Thursday morning,” they say.

And then we see those same characters — characters we relate to, in a world we recognize — as they begin to become powerless; their bodies brutalized, their priorities shifting to mere survival. In the reeducation center, where women are tortured and broken into becoming handmaids, Moss and Wiley’s characters join in with a group’s chant, shaming a woman for the fact that she was raped. During the monthly “ceremony,” Moss submits to being held by the woman who owns her, Mrs. Waterford (Yvonne Strahovski), while she is raped by the woman’s husband, Commander Waterford (Joseph Fiennes). And when Bledel’s lover is hanged, the only possible protest comes from her eyes, her mouth muffled by some sort of mask. I will never forget her eyes. If the book is a cautionary tale, if reading it is like a warning to look both ways before you cross the street, the performances of Moss, Wiley, and Bledel make watching the show like being hit by a bus. We feel their injury in our bodies.

Zadie Smith, in her essay “Man vs. Corpse,” writes that, “I’m a sentimental humanist: I believe art is here to help, even if the help is painful — especially then.” Smith is looking at a picture of a corpse. “Imagine being a corpse,” she writes. Hulu’s series invites us to imagine a lot of things, though perhaps the scariest is imagining the loss of control over one’s body, imagining being forced to have children. Many people now living in America don’t even have to imagine. Nevertheless, I believe The Handmaid’s Tale is here to help, and maybe in more concrete ways than expanding our capacity for empathy. Already the image of the handmaid has become a disturbing and powerful counter-symbol for women’s rights, employed in protests where those rights are imminently in danger. Which is good news, given that we now live in a world where it’s possible to imagine Vice President Mike Pence watching The Handmaid’s Tale and thinking, “What a brilliant idea. I can’t believe a woman had it.”

Why People Don’t Like “I Love Dick” (Hint: Because It’s About Women)