Reading Lists

8 Books that Wouldn’t Exist Without Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’

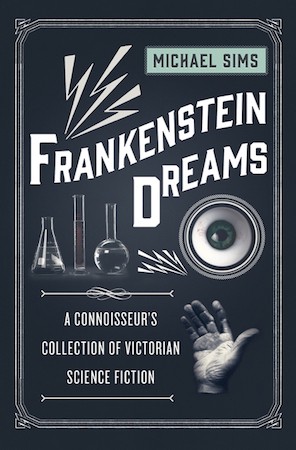

On the book’s 200th anniversary, Michael Sims, author of ‘Frankenstein Dreams,’ collects Frankenstein’s hideous progeny

In the summer of 1816, a pregnant, unwed teenager had a nightmare.

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin — not yet Mary Shelley — was at Lake Geneva, Switzerland, with her lover, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. The rainy summer often forced them indoors. Once, at the villa that Lord Byron was renting on the lakeshore, the party entertained one another by reading from a recent anthology of German ghost stories, Fantasmagoriana. Byron challenged them to each write a horrific fiction. “Have you thought of a story?” Shelley recalled that she was asked each morning — “and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.”

Then she suffered what would become one of the most famous nightmares in history: “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion.” The narrative grew in her imagination, and she followed it. Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus was published — anonymously, like so many novels of the time — in 1818. Not until the second edition four years later did Shelley put her name on the title page.

New ways of thinking about nature (and human nature) require new ways of writing, and the writer we now consider the founder of science fiction saw the need for fresh metaphors while still a teenager. She confidently declared her position, midway between science and fancy, in her introduction to the first edition: “It was recommended by the novelty of the situations which it develops; and, however impossible as a physical fact, affords a point of view to the imagination for the delineating of human passions more comprehensive and commanding than any which the ordinary relations of existing events can yield.”

Young Mary’s first novel has lasted, in part, because the central figure quickly strode off the page and into popular culture.

Shelley’s sentence could serve as a manifesto for her novel’s successors and for fantastic tales in general. Frankenstein explored the ancient themes of literature: anguished dread of mortality, the consequences of obsession— inevitably hubris and its consequent ate—and the divine retribution that in mythology always follows overweening pride.

Young Mary’s first novel has lasted, in part, because the central figure quickly strode off the page and into popular culture. Nowadays the cobbled-together, nameless “monster” — long mistakenly known by his creator’s name — is familiar to millions who have never read the novel. He is a stock figure in horror movies, a favorite of editorial cartoonists, a cautionary fable about science.

Tales of creation gone awry range from Pinocchio to the Gingerbread Man, from the Clay Boy of Czech folktales to the endless recreations of the protean monster conjured by Victor Frankenstein. The critic Michael Dirda listed some of Mary Shelley’s themes apparent to an attentive reader: “the persistent interconnection of sex, birth, and death; the mirroring of monster and creator; the conflict between instinctive goodness and the societal creation of the criminal; the power of nature to soften and civilize; the human yearning for sympathy and love.”

In the 200 years since the novel’s publication, we’ve had bad imitations and truly inspired Frankenstinian progeny. Spanning the late 1800s to the Brexit era, here are 8 books that owe their life to the original creator.

Mary Shelley’s Revision: 1831

The first book inspired by young Mary’s 1818 book was her own 1831 revision of it. By this time, she had published other novels, established herself, somewhat transcended her scandalous youth, and become the keeper of the Romantics’ flame. The 1818 edition presents a stronger, unadulterated view of Shelley’s dark vision. In her introduction to the 1831 update, Shelley explicitly stated, “I have changed no portion of the story,” and claimed that her revisions were limited to matters of style. Actually she greatly altered the spirit and implications of the story. She also saluted the memory of her brief but life-changing romance with Percy Shelley, who had died in a boating accident on the north-western coast of Italy in 1822. And she removed the epigraph that haunted the opening in 1818, from Milton’s Paradise Lost:

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me man? Did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me? —

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson’s now legendary 1886 novella The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde could not have been written without Shelley’s pioneer novel. Stevenson wove many contemporary issues into his story, beginning with well-known case studies of dual personality, but they gained resonance when he mixed in evolutionary fears and the recent notion of the violent criminal as an atavistic reversion to our species’ brute past. Like Shelley, Stevenson explored the horror of unleashing the primitive id. Two years later, when Jack the Ripper began to terrorize Whitechapel, the newspapers immediately referred to Mr. Hyde, to the lurking midnight viciousness of humanity.

“The Golem” by Avram Davidson

In the original Hebrew Bible and the later Christian Psalms, the word golem meant a kind of unformed material, a potent clay. Over time it became the name of the classic Hebrew Frankenstein, an anthropoid creature formed of mundane earth and animated by supernatural rather than by science-fictional methods. Victim and villain, as potent in its ambiguity as Frankenstein’s monster, the golem stalks through folklore and into recent literature. It is difficult to imagine a more dryly amusing monster story than “The Golem” (1955) by the richly talented Avram Davidson, known mostly for his science fiction. It’s available in numerous collections.

Frankenstein Unbound by Roger Corman

The British science fiction writer and historian of science fiction, Brian Aldiss, sent a time-traveling twenty-first-century character back to Shelley’s time in his bloody but thoughtful 1990 novel Frankenstein Unbound. The title and big-picture themes echo the work of both Mary Shelley and her husband Percy’s poetic drama Prometheus Unbound. Roger Corman, director of everything from a series of Poe adaptations starring Vincent Price to the pioneer biker movie The Wild Angels, adapted Aldiss’s novel in 1990.

The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein by Peter Ackroyd

Frankenstein lumbered easily into the twentieth century. 2009 saw publication of The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley’s versatile and prolific countryman, Peter Ackroyd. Author of books about everyone from the poet Thomas Chatterton to London Underground, as well as of a biography of Dickens as manically creative and long-winded as its subject, Ackroyd knows how to conjure the past. This novel is sometimes pastel in hue and pedestrian in pacing, but it reaches heights of thoughtful homage to Shelley’s original.

Hideous Love by Stephanie Hemphill

As recently as 2013, Stephanie Hemphill tackled a lyrical free-verse account of creator and monster in Hideous Love. As in her verse novel Your Own, Sylvia, about Sylvia Plath, Hemphill was inspired again by the genesis of a troubled young female writer. She focuses on Shelley rather than upon Frankenstein and his monster, but young Mary’s Gothic imagination grew out of this period.

Man Made Boy by Jon Skovron

In 2015 Jon Skovron published a book that I have not yet read but which is on my bedside table. The beautifully refractive title Man Made Boy hints at the complexity and wit of this acclaimed YA novel built around the story of Boy, the ill-fated offspring of Frankenstein’s monster and his equally scary bride. Boy has never walked freely in the world above the catacombs beneath Times Square, from which he and his family and other legendary monsters appear in public as a theater troupe. As much a child of the new millennium as of mythic monsters, Boy is a computer wizard who conjures a virus that, naturally, gets as out of control as the genesis of his own parents.

Spare and Found Parts by Sarah Maria Griffin

In the era of Trump and Brexit, it should be no surprise that the mythic tale of a raging monster inspired by blind hubris continues to flourish. The bleak year of 2016 saw publication of Spare and Found Parts, an elegant and thoughtful debut YA novel by Sarah Maria Griffin. Set in an apocalyptic near-future following a technological breakdown, the story follows Nell Starling-Crane, whose loudly ticking clockwork heart sets her apart even from the many other characters whose prosthetic augmentations enable them to survive in this anti-technology era. Secretly outwitting the ban against technology, young Nell builds an android whose creation and adventures raise as many thoughtful questions as its inspiration — Mary Shelley’s nightmare precisely two centuries earlier.