Reading Lists

8 Medieval Texts that Prove Things Haven’t Improved that Much

A few centuries later, and the literature of feudalism is still asking relevant questions about class, women, and sexuality

For legitimate reasons, many of us consider the Medieval period a backwards time. Women were second-class citizens, homosexuality was illegal while misogyny was lawful, and religion controlled everything.

But the Medieval period was also a rich and complex time. History is written by the oppressor, so we don’t hear as much about the women from this era who were running businesses, leading their communities, having healthy sex lives, and — yes — writing. Entering college, an English major with her eye set on teaching, I had no love for Medieval literature. I thought it was boring, outdated, so far removed from my own life, experience, and the conversations I had around those topics. And then, as they magically do, a really fantastic professor changed that. In Medieval lit, we read Chaucer — all of Chaucer — in the original Middle English. Three years later, I was starting grad school with a concentration on gender in Medieval literature.

I return to Medieval literature again and again. Each time I pick up one of these texts, I find them full of relevant questions about gender, class, sexuality; they help me examine encounters that I have now, in 2018. The following texts prove that the conversations we are having currently about women’s writing, gendered experiences, and female authority are similar to those that writers like Marie de France, Julian of Norwich, and others were having as early as the 12th century. Which tells me that either the Medieval period was much more progressive than it’s given credit for, or the 21st century intelligentsia isn’t as advanced as it thinks.

Piers Plowman by William Langland

Although written by one of the many, many white men that fill the Medieval lit canon, Piers Plowman is a standout work. It’s a strange, distorted story of a man who splits his time almost equally between sleeping and waking. In both dreams and waking moments, he finds himself on a journey of theological, political and social discovery. In Piers Plowman, women are given agency, which isn’t as uncommon in literature of this period as people might expect. But Langland’s women are also central to major philosophical discussions — this text touts values that, hundreds of years later, would become tenets of socialism and liberation theology, making concise arguments for giving all of your money to the poor and questioning class hierarchies.

Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich

In 1373, Julian of Norwich was given her last rites on her deathbed. She then experienced a series of visions, depicting Christ’s crucifixion in gory detail, which miraculously restored her to health. She spent the rest of her life in a small room, as an anchoress, giving spiritual guidance to her local community. Revelations of Divine Love is her theological thesis on Christ, suffering, and of course love. Texts like this, written by mystics, were daring at the time because women were not meant to write, much less write about theology or the Church. Julian’s text, some 600 years later, reads as a complex essay by a woman ruminating on the trauma of a near-death experience.

The Fire of Love by Richard Rolle

Richard Rolle is one of the few male Medieval mystics, mostly because the term “mystic” is a gendered term. The label suggests emotion and otherworldliness; minus the etymological connection, it’s associated with women in a similar way to “hysteria.” But Richard Rolle’s Fire of Love is full of sensual, mystical energy that disregards the limitations of the gender binary. His work was extremely controversial in his time, for a number of reasons. He held a strong fascination with women’s clothing, chose a life of hermitude, and his writings on God and Christ read, today, as overtly sexual — all making him a popular subject of Medieval queer theory.

Lais of Marie de France by Marie de France

Marie de France was a French poet who lived in England in the 12th century. She’s most famous for her lais, which are short poems that tell stories of chivalry and romance. The Arthurian lais “Lanval” is what she’s known for, but it’s “Bisclavret” that earns her a spot on this list. “Bisclavret” is considered one of the first werewolf stories and, while it’s not explicit, it’s easy to read as a queer narrative. It tells the story of a young man who is the King’s favorite knight. His wife starts to worry because he’s disappearing into the woods every night, and returning “happy and gay.” She fears he’s living a double life with another lover, but soon finds out he’s a werewolf. She leaves him for another man, and he goes to live in the castle with the King, happily ever after — just your classic gay werewolf tale.

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

It’s difficult to write a list of texts from the Middle Ages without including Chaucer. Chaucer is certainly the most prolific Medieval writer, and his works are rich, determined, and funny. He plays around with genre and language in ways that shock and delight even now. I chose The Canterbury Tales over his other work because it’s full of bawdy women and biting class critiques. There is not enough space here to go down the list, so I’ll just throw out my favorite: to spurn his unrelenting advances, a young woman farts in a man’s face.

The Book of Margery Kempe by Margery Kempe

The Book of Margery Kempe is a lot — the first autobiography written in English and penned by a woman who lived a textured life. Margery Kempe defies every preconceived notion most people have about women in the Medieval period. Breaking the stained glass ceilings of her time and writing this book is even more impressive given that she wasn’t a member of the upper class. She lived independently running a brewery. She saw visions of Christ and cried openly in the streets, overcome with emotion. What sets Margery’s book apart is that it’s a theological doctrine written by a devout mystic, yes, but it’s also a memoir written by a woman about her own body, her own emotions, her own experiences.

The Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan

Whenever I see Molly Roy’s imagining of a NYC subway map with stops all named for women (an illustration in Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Shapiro’s Nonstop Metropolis), I think of Christine de Pizan. Christine de Pizan wrote a text around an idea that Virginia Woolf (and Molly Roy) would pick up hundreds of years later: What would the world look like if women were afforded the same opportunities as men? In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf invented Shakespeare’s fake sister, who wrote successful plays because she was given the funding, education, and space her brother was. Christine de Pizan rewrites whole chunks of history to situate women from famous myths and histories in one city and names monuments after them to show what a city who values women would look like.

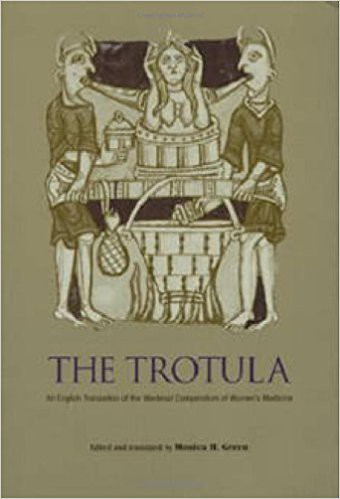

The Trotula (author unknown)

The Trotula texts are actually three medical texts from the 12th century. They explored different areas of “women’s medicine,” touching on everything from menstruation to makeup. The practices within, inaccurate and dangerous, were used to backup pretty much every misogynistic idea Medieval men had about Medieval women. It’s difficult to read in 2018, and it would have been horrible for everyone with a uterus to read when it was published, due to it’s grotesque renderings of anatomy, bizarre medical practices, and the language it uses to describe women. It was thought to have been written by a woman — Trota of Salerno, a medical practitioner — but that’s been hotly, and mostly successfully, contested. There’s no doubt it had a huge impact on how men approached women’s medicine for centuries. I’m including this text on the list not because it should be followed, but because it raises questions relevant to today: who are we going to let shape the conversation about women’s health? How far have we gone to take away women’s authorities on their own bodies? This text and history have shown us what happens when the wrong people and messages dictate power over women. Trotula, as I said, was published 9 centuries ago. Don’t we think it’s time to break old patterns?