Books & Culture

Finally, a Music Novel for Middle-Aged Tape Collectors

So many music novels are about rock musicians—it's time for consumers and collectors to get their due

Great novels about rock music tend to be populated by, well, rock musicians. Don DeLillo’s Great Jones Street, Francesca Lia Block’s Weetzie Bat, Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet, David Keenan’s This Is Memorial Device, and Stacey D’Erasmo’s Wonderland are all immersive, compelling reads, even as the stories they tell and the music they describe are radically different. These are books that detail the fictional lives of musicians, yet they also have plenty to say about the act of listening, and of the ways that music can change lives.

A number of notable novels about rock published in the United States this year wrangle with questions of musical ephemera. In the case of Nell Zink’s Doxology, that’s very literal: its first half traces the rise of a singular musician and explores his impact and legacy in the second half, after he’s met an untimely demise. Sarah Pinsker’s A Song For a New Day is set in a near future where all public gatherings have been made illegal due to security concerns. In it, Pinsker raises a parallel question: what is the place of rock music (or, really, any sort of music) without live performances, music or merchandise, or really any physical presence at all?

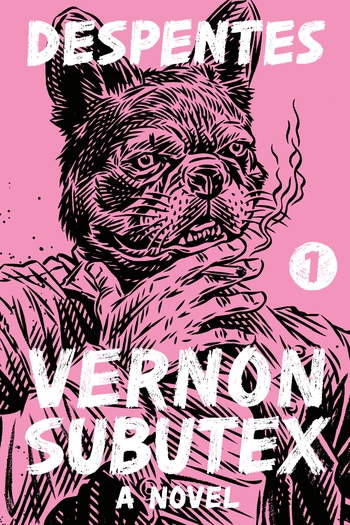

And then there’s Virginie Despentes’s Vernon Subutex 1, which offers a very different take on the rock novel, albeit one that’s every bit as compelling as its cohorts. Why? Because it zeroes on the life of a music enthusiast rather than on someone who’s dedicated their life to making music. Despite the fact that there are far more music obsessives in the world than working musicians, the latter are far more represented in the pages of novels than the former.

For some, it’s paying six figures for Kurt Cobain’s old sweater; for others, it’s collecting set lists from DIY punk shows.

Despentes has been a singular literary figure in France since the publication of her first novel, the controversial Baise-moi, in 1993. Vernon Subutex 1, translated into English by Frank Wynne, is the first part of a trilogy that was a massive hit upon its release. In its English translation, it was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize after being released in the U.K. — and that’s just the first volume. What Vernon Subutex 1 offers is a fascinating question: can you succeed in writing a rock novel where the focus is on musical ephemera? But this isn’t some sort of Oulipian gesture Despentes is making; instead, it’s a way of taking a ground level view of music, and the way it filters down to its listeners. For some, that’s through vinyl; for others, Spotify. For some, it’s paying six figures for Kurt Cobain’s old sweater; for others, it’s collecting set lists from DIY punk shows. What Despentes is after in Vernon Subutex 1 is this kind of energy.

This isn’t to say that Despentes’s novel is the first high-profile rock novel to avoid placing a musician at its center: both Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity and Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia come to mind. But even those novels featured musicians among their cast of characters, even if they weren’t at the center of the book. In Despentes’s novel, the only musician of any significance is dead before the novel even opens, with his absence serving as the spark that drives several of the other characters along. And as befits a novel published at a time when a musical thinkpiece is just as likely to be about how we listen as what we’re listening to, it addresses a number of larger concerns — it’s one of several novels that seem eminently tapped into the changing world of contemporary music.

In Despentes’s novel, the title character is a middle-aged man, and the former owner of a long-running record store called Revolver which folded due to the rise of digital music. Vernon is initially portrayed as a fairly misanthropic type: a hermit-like figure living in solitude, watching pornography and thinking back on his romantic relationships of years past and his friends who have died in recent years. The latest of those is Alexandre Bleach, an iconic rock star and old friend of Vernon’s who’d covered the rent on Vernon’s Paris apartment.

After Alexandre’s death, Vernon is evicted and begins a process of frantic couch-surfing to stave off homelessness. The scene of him packing abounds with a meticulous attention to ephemera: “He fills the bag. Headphones, iPod, pair of jeans, Bukowski’s letters, couple of sweaters, boxer shorts, signed photo of Lydia Lunch, passport.” There’s a lot that this brief array of items can tell the reader about Vernon, for good and for ill.

It’s when Vernon becomes displaced that he reconnects with old friends and former lovers, many of whom have as complex as a relationship with music as he does. When Vernon recalls the time he spent with a friend dying of cancer, Despentes is quite specific about how they spent their time. “So instead they listened to the Cramps, the Gun Club, and the MC5, and they drank beer while Bertrand still could,” she writes.

This is par for the course for the early chapters of the novel, where nearly every character is introduced with their musical tastes as part of the characterization. It could feel like shorthand, but the extent to which it’s used ends up working as a kind of synecdoche for the larger musical milieu in which these characters dwell. That sense of the centrality of music comes up elsewhere, as when the origin of Vernon’s penchant for being a flaneur coincides with a very specific moment in musical history.

He often went walking at night. It was a habit he had picked up in the late eighties, when metalheads started getting into hip-hop. Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys were signed to the same label as Slayer, which made the connection.

The use of music as shorthand also ties in with some of the novel’s other themes. Just as music and musical ephemera are used as methods of characterization, so too does the absence of certain types of music signify other things. Another of Vernon’s old acquaintances, Jean-No, is described as having once been fond of the likes of Minor Threat, Foetus, and Rudimentary Peni — but as he grows older, Jean-No’s aesthetics curdle into something else. “When he turned forty, in an effort to seem more classy, he started getting into opera,” Despentes writes. “He dressed like a Playmobil figurine in his Sunday best and he spouted alt-right bullshit ten years before it was fashionable.”

Musical ephemera can take many forms; periodically, Despentes notes which video clips Vernon has opted to post on Facebook, his one constant for communicating with the world as he moves from apartment to apartment. And to the extent that this novel has a MacGuffin, it comes in the form of another sort of ephemera: a series of videotapes that the now-deceased Alexandre recorded at Vernon’s apartment. “It’s, like, my last will and testament, man, you get it?” Alexandre tells him — and soon enough, several parties with very different designs on the tapes begin to seek Vernon out.

Having the spending power to collect musical ephemera implies a certain socieconomic background.

Vernon Subutex 1 is a novel about music and musical ephemera, to be sure, but it’s also about aging and the rise of reactionary politics. This is tied up somewhat in questions of class: both in the anti-establishment working class motif out of which a lot of music is born and via the way several of the novel’s characters have found themselves living middle-class lives as they settle into middle age. Having the spending power to collect musical ephemera (and the space to store it) implies a certain socieconomic background — one that’s become more politically charged in recent years, with the rise of right-wing populist movements lining up with nativist rhetoric playing on middle-class insecurities. Vernon himself is something of a misanthrope, but compared to the nativist rhetoric some of the other characters he encounters utilize, he ends up coming off more and more likable by comparison. The way that so many of Vernon’s old friends have shifted their politics to the right is one of the novel’s more alarming motifs, and it goes hand in hand with the novel’s take on social media.

“The internet has created a parallel space-time continuum where history is written hypnotically at a speed much too frantic to allow the heart to introduce an element of nostalgia,” Despentes writes a little less than halfway into the novel. Despentes is far too savvy to create an overly simplistic “physical media good, digital media bad” dialectic here: Vernon ponders how the internet effectively put his shop out of business, but also allowed him to make a tidy profit from his leftover inventory on eBay. And the ubiquity of Facebook allows him to remain in communication with numerous old associates once he’s evicted. But Despentes is also aware of the downside of the growth of the internet as a common space: the juxtaposition of the internet’s rise with the rise of reactionary politics within the book’s narrative is hard to ignore. Also hard to ignore: the fact that this novel is essentially about paring away all of the accumulated stuff of a life, as a middle-aged man with skills eminently rooted in an era whose best days are behind it faces an uncertain future. There’s a tension throughout Vernon Subutex 1, in that its title character is at once central to the narrative and increasingly irrelevant to the novel’s universe. It’s the kind of paradox expansive fiction like this can raise and grapple with better than almost any other art form.

Vernon Subutex 1 takes a largely cynical stance throughout — though it leads to a climax that’s anything but. As for the other novels alluded to earlier, they each carve out their own space. A Song For a New Day is more idealistic, even as it grapples with the question of whether a government that wants to outlaw live music is preferable to an all-consuming corporation that simply wants to control it. And Doxology grapples with some of the same questions as Vernon Subutex 1 — namely, about life in the absence of a magnetic and talented musical presence — but is set in a milieu of characters who are more well-positioned to make a living outside of the music industry. If the three-band bill is a kind of platonic ideal for a punk show, these three novels serve as the literary equivalent of just that.

It’s also no coincidence that all three of these books deal in some way with generational shifts within music — or, more broadly, aging in a milieu where youth is lauded. But all of them also tie in the dovetailing of technological advances with corporate control with reactionary politics — whether that’s in the early-’00s setting of Zink’s novel, the near-future setting of Pinsker’s, or the present-day setting of Despentes’s. Does music lose some of its revolutionary potential when you strip away the physical elements that accompany it? And might that be the difference between holding off some elements of political oppression? Vernon Subutex 1 offers no definitive answers, but the points it makes along the way are chilling enough on their own.