Novel Gazing

A Series About Teens Who Turn Into Animals Taught Me How to Be Human

How the ‘Animorphs’ books eased my transition into adulthood

Novel Gazing is Electric Literature’s personal essay series about the way reading shapes our lives. This time, we asked: What book was your feminist awakening?

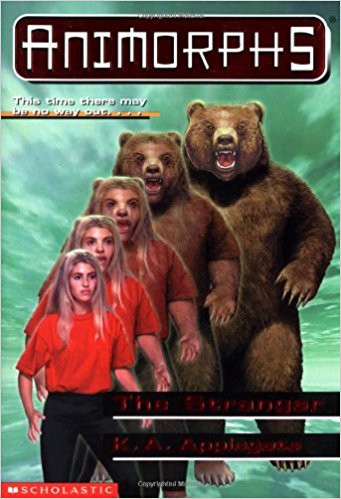

When I was nine years old, my best friend Max moved away. We had spent almost every day of elementary school together during recess and after school, making up new worlds and telling stories, even though as we got older our boy-girl friendship was something other kids sometimes teased us about. After Max moved, I still went to visit him every couple of months in New Jersey, and on one visit he showed me the book he was reading, part of a new series he was obsessed with. On the cover was a pretty blond girl — the kind of girl you might see advertising Coca-Cola or teeth-whitening chewing gum — turning into a grizzly bear. There were five versions of the girl. In the first she looked normal, totally human. In the next version, her arms and face thickened, rounded, and her face became newly hirsute. Behind that version, the girl’s face became covered in fur, and her open mouth showed sharp teeth. In the fourth, her blond hair had faded into her fur-covered torso, and her teeth had turned weapon. In the fifth image, she had gone total grizzly, covered in fur and growling.

“Weird cover,” I said.

“She’s an Animorph,” Max said. Then he explained the precipitating incident of the Animorphs series: A group of middle schoolers find a dying alien in a parking lot at night. The alien warns them that the Yeerks, a species of mind-controlling slugs, have begun to infect the human race. Someone you love might be controlled by a slug that has crawled into their mind and you wouldn’t even know it. The dying alien gives the kids the power to morph — to change into animals — and they begin a secret guerilla war against the Yeerks. The book Max was reading now was Animorphs #7, The Stranger.

It was a lot of information to absorb. So I focused on the cover, the girl changing into a bear. That same year I’d been given one of those you-are-on-the-precipice-of-puberty books. I’d seen other books or pamphlets too, during doctor’s visits or in other kids’ bookshelves. It seemed there was a whole genre of writing readying me for puberty, educational books in which someone inevitability asked, “What is happening to me?” The question always sounded like the thing someone in a horror movie would say the second before they werewolfed hard.

In the what-is-happening-to-me book I’d been given, one page showed all the stages in a girl’s transformation to woman. On the left side of the page, a drawing of a naked seven year old girl. Next to that image, a drawing of the same girl at ten, her hips rounding out. Another around thirteen, with breasts and a dark patch of pubic hair. Another around nineteen, all curves and huge dark nipples. Before my eyes, a naked girl morphed into a naked woman. That undeniable change seemed echoed on the cover of Animorphs #7, which I stared at for a while. In my mind’s eye I saw a farrago of girls going through puberty and girls turning into grizzly bears.

In my mind’s eye I saw a farrago of girls going through puberty and girls turning into grizzly bears.

I guarantee you this: Never once did I actually think, “Oh my god, I am on the verge of animorphing into puberty.” But the cover stuck with me enough that I convinced my mom to buy Animorphs #7 for me at the next Scholastic book sale ($3.99). I opened the book with some part of my brain expecting a science fiction story, and some deeper part of my brain hoping for the guide the what-is-happening-to-me book failed to be.

I didn’t just need a guide to puberty. Since Max had moved away, I had an increasing sense that I was failing to morph socially. I tried to ingratiate myself into a group of girls in my class at school, mostly on the basis that I was a girl and supposed to hang out with other girls. They were not not nice to me. Still, there was a certain gap. I lived in Manhattan, but my dad was our building’s super and our apartment in the basement was rent-free. It wasn’t that we couldn’t get by, but we certainly didn’t have what many of these girls came equipped with: country homes, designer clothes, an impressive range of extracurriculars. I did my best to make up the difference by doing well in school and smiling hard at everyone. It worked okay.

One of the girls had invited me to her birthday party, which, she informed me, would also be a makeup party. Making up for what? Ha-ha-ha-ha, she said, and I blushed, and she said there would be lipstick, mascara, other things, plus a fancy camera. We would each have our photographs taken in our lipstick and mascara and other things, and the photographs would be printed in sepia tones and placed for us in a golden frame and we would get to take the photo and the frame home that very same day.

At my own birthday party that year, my parents had suggested we all take the Staten Island Ferry back and forth a couple of times. It was free.

The makeup party sounded like it could be fun, and I definitely didn’t want to be left out, so I agreed to go. The day of the party I wore my hair down and put on a shirt I deemed “tastefully tie-dyed.” But once I got there, I quickly became terrified. Everyone put on so much makeup they looked like glamorous clowns, or children competing at a beauty pageant. Now these girls I knew stared sultrily into the camera like strangers. They batted their eyes, they posed in feather boas. I sat there unsure of myself, unready to be a part of whatever territory these girls sashayed toward.

I sat there unsure of myself, unready to be a part of whatever territory these girls sashayed toward.

In the end, I only put on a little makeup, a bit of blush and lipstick. In the glamour shot from that day, I am smiling but I am not showing my teeth, which the students at the NYU College of Dentistry would soon try desperately to straighten out. Everyone else’s photographs looked cutely silly (or sometimes cutely creepy) in their subjects’ attempts to seem adult. My photograph, with its sepia tint and closed-lip smile, resembled the old-fashioned daguerreotype a movie might display on a mantle to set up the presence of a child ghost. I looked pale and uncomfortable and the blush on my cheeks seemed to hint at an oncoming nineteenth-century-style Little-Women-ish death from scarlet fever.

I had failed at the makeup party.

Animorphs #7, the first Animorphs I ever read, is narrated by Rachel, the blond female Animorph who likes shopping and gymnastics. She is also the most ruthless and reckless warrior of the Animorphs, which later becomes a key character arc. In #7, there are only hints at her ferocity. The book opens with Rachel wanting to scare an elephant trainer into ceasing to use his cattle prod to control his circus elephants. So she sneaks into the elephant pen at night and morphs into an elephant herself. “People say I’m pretty,” Rachel confides in the reader. “I don’t know and I really don’t care. But I’ll tell you one thing — no one who has ever seen me morph into an elephant ever used the word pretty to describe it.” There is a real grossness to all descriptions of the morphing process, a grossness that helps them seem less like fiction. “I felt the teeth in the front of my mouth run together,” Rachel narrates as she turns into an elephant, “and then begin to grow and grow into long, spear-length tusks. It’s a creepy sensation, by the way. Not painful, but definitely creepy.”

Not painful but definitely creepy. This felt refreshingly truthful. In the what-is-happening-to-me books, the process of turning from a girl into a woman was often described as beautiful. Natural. Normal. But nothing about that process seemed normal to me. And a fair amount seemed unsettling. I liked how Animorphs described the morphing as awkward, and a little disgusting. It reminded me of the in-between space the girls had been in at the make-up party.

The process of turning from a girl into a woman was often described as beautiful. Natural. Normal. But nothing about that process seemed normal to me.

Once Rachel turns into an elephant, she roars an elephant’s trumpeting roar, and the trainer comes running. She waits until he’s all the way in the pen, and then she grabs him around the waist with her trunk, lifts him up and, using the Animorphs’ gift of thought-speak (they can think right into someone’s mind while in a morph, sort of like a psychic form of texting), claims to be from the International Elephant Police. She tells the trainer there have been some complaints about him and that he must stop using the cattle prod to control his elephants. If he doesn’t, she will come back and destroy him. The trainer acquiesces to her demands and she tosses him twenty feet away, where he lands safely (so says the narration) on a tent.

I was exhilarated. Here a pretty girl had shed her pretty girl-ness, morphed into an elephant, ordered a man to stop his wrongdoings, and succeeded. She had changed — awkwardly and disgustingly — into something more powerful. She had been listened to by someone who in most cases would be the more powerful male adult.

Later in the book, Rachel and the other Animorphs morph into cockroaches in order to spy on the Yeerks. This was more familiar to me than the whole elephant thing. In our basement apartment, we were always dealing with cockroaches. After Rachel turns into a cockroach, she finds the cockroach brain is full of fear. “When you first morph into an animal, it is almost always a struggle to adjust to its particular instincts,” she says. This, too, made sense to me. When you turned into some other form, you were faced with new demands, both internal and external. Certainly I’d felt this at the makeup party — my desire to run and to fit in, my desire to appear attractive but not necessarily womanly. But only a few pages later Rachel has grappled with much of the cockroach’s fear. She admits it’s pretty cool how, in the roach form, she can run straight up most walls.

Rachel’s ability to shift forms didn’t just make her powerful, but expanded her perceptions of the world. Animorphs #7 began to offer me a whole new world of different transformations a person could undergo. It wasn’t that I actually believed I would turn into an elephant or a cockroach. I simply appreciated the beauty of being offered an escape from the relentless narrative of a single transformation: girl to woman. In Animorphs, things could be funkier than that. You could change in other ways. You could change into something more powerful, or something more fearful, and all these changes could lead you to ultimately morph into someone who was more empathetic.

You could change into something more powerful, or something more fearful, and all these changes could lead you to ultimately morph into someone who was more empathetic.

I’d love to say the lessons I learned from Animorphs had an immediate effect on me. I’d love to say I went to another makeup party post-Animorphs #7 and that I was blissfully empowered. I’d love to say that I put on makeup so I looked like some kind of formidable beast, that I smiled huge at the camera, fiercely toothed and fiercely clawed. I’d love to say that when I put on makeup, I put aside my insecurities about myself around these girls with their above-ground apartments and extracurricular well-roundedness, and just embraced who I was and who I might be.

But nope. I went on to avoid those kinds of parties like the Yeerks themselves might be in attendance. Instead of more makeup parties, I let myself become deeply obsessed with a book series. I spent hours and hours analyzing Animorphs online with total strangers and, when the Animorphs TV show came out on Nickelodeon, ranting against all the inaccuracies of the television show. In a way, rather than obviously transforming me, Animorphs — to use another animal metaphor — provided for me a kind of cocoon, a safe space where I could hang out and think about what kind of animal I might want to turn into, or at least what kind of metamorphoses I might want to write about.

Even more essentially, inside the cocoon of the series, I saw stories could help you grow in ways that felt more interesting than the growth offered by the what-is-happening-to-me books. Stories could be an escape, yeah, but they also could briefly “morph” you into the mind of somebody else, expanding your sense of the world. When I write stories now — even when I write stories about my past self — there is always that sense, however fleeting, of transformation. Of hanging out in some other creature’s headspace.

At the end of the story, I morph back into myself, only I’m changed. I’ve been some other thing, something the what’s-happening-to-me books could never have predicted. But Animorphs in some way predicted these shifts for me, these expansive moments that were the result of hurtling into and out of puberty — that were the result of encroaching adulthood. A new form, the series had hinted, might give you the ability to look harder not just at the shape of your own experience, but also at the shapes of other lives.