Lit Mags

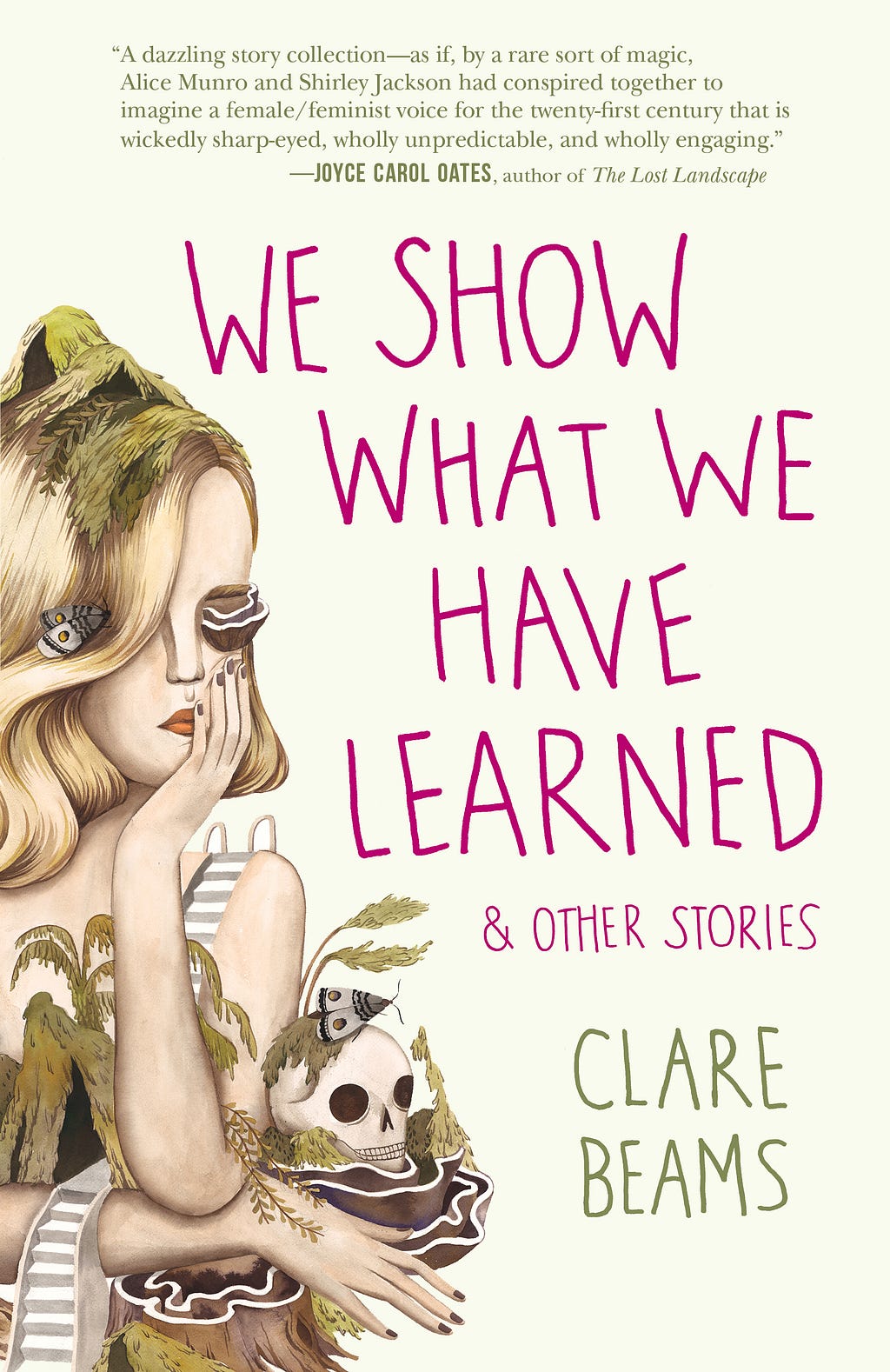

All the Keys to All the Doors by Clare Beams

A story about what it takes to raise the village

AN INTRODUCTION BY MEGAN MAYHEW BERGMAN

Clare and I have known each other since before we were mothers or writers. I suppose we were always writers underneath, but we met on a summer day in the backyard of my husband’s childhood home in our early twenties. Our husbands, men of science, grew up together in a small Vermont town. My eldest child cut her first tooth during the ceremony of Clare’s wedding, on a cliff overlooking Lake Champlain. We had lives that intertwined naturally, lives that didn’t require us to like the other’s work, or pause on the sound of one another’s sentences.

There is a cutting strangeness and profundity afoot.

But I happen to love her work, and the skill of her sentences. Clare constructs stories with impeccable clarity and elegance. Upon reading her, you make it to the third or fourth paragraph and realize this is not the restrained narrative you expected, that there is a cutting strangeness and profundity afoot. In “All the Keys to All the Doors,” we read the classically beautiful line, “Middleford was a tablecloth of a town,” — but any reader lulled into believing they are in for a temperate tale awakens a few sentences later.

Beams tells of the aging Cele, who hired old men not for the strength of their backs, but “for their discretion.… ‘Something’s funny with the building.’”

If one looks deeply at the stories in Clare’s accomplished debut We Show What We Have Learned, one sees the way — with their strange and occasionally grotesque notes — that these stories reach out to contemporary pain and questions. In the case of “All the Keys to All the Doors,” the question is devastating and universal. What is it like to “live with unlivable things”? Where does one put the anguish accumulated during a tragedy, or a lifetime? Clare is an author you can trust to explore the answer.

Megan Mayhew Bergman

Author of Almost Famous Women and Birds of a Lesser Paradise

All the Keys to All the Doors by Clare Beams

Clare Beams

Share article

On that first Tuesday in March, the assistant principal came to tell Cele what happened. She answered the door still in the thick bathrobe she wore against the achy morning chilliness, still holding her second cup of coffee. His lips were gray around the edges. It was all over; the boy who’d done it was dead. For some reason the doors to the school and the third-grade classroom hadn’t been locked. There will be no more Tuesdays in Middleford, Cele decided while the assistant principal spoke. She looked over at Kaitlin’s dark house and willed her to keep sleeping. No more month of March either. She opened her mouth to tell him so.

“What?” she asked. “What did you say?”

Middleford was a tablecloth of a town, stretched loose and green over gentle New England hills. Anchored by Cele’s gifts. Cele gave buildings the way other women gave candies linty from the bottoms of their purses. The town hall, the library, the middle school, the high school, the rec center. Gracious hulks of buildings, Greek temples swathed in brick, monumental. She gave a monument, too, dedicated to the general war dead, which the town festooned with flags on Memorial Day.

These buildings’ caretakers were all old men, and Cele hired other old men to replace them when they died. People in town wondered absently how these men, so old, managed to keep the buildings so spotless and clean lined. There was widespread mild worry about their backs. Cele didn’t hire them for their backs, but for their discretion. Forty years ago, the first of them had come to talk to her, three months into his tenure at the town hall (the first of her gifts, answering the first, most urgent need, or so she’d then thought — putting the main in Main Street). Sam Brewer, a stooped man of seventy, who took off his hat when he spoke to her. “Something’s funny with the building.”

“Funny?”

He crossed his arms. He didn’t want to say the crazy thing he had come to say. Cele didn’t know what it was, though some corner of her had suspected that there’d be something. That faint itching knowledge was what had made her hire Sam for the job in the first place and not some strapping, younger, louder man.

She was quiet. She was only thirty, that long-ago morning, but she’d already learned the power of silence, the way it let you set terms.

Sam finally spoke. “There’s no work for me to do. I dust and I mop and I sweep, but it’s just to be doing something. There’s never dust, or dirt, nothing. Sometimes I’ll even see somebody’s dropped something, or left a footprint, but when I come back to clean it, it’s gone already. Like . . .”

He let his eyes roam over her living room: The mantel with the blue-and-white Chinese vases her father had set there when he bought this house before Cele was born, with some of the money Cele herself would quadruple. The worn-in chair that had come with Garth when she’d married him. Her father had been dead for ten years, on that morning of Sam’s visit, and Garth for two. It was in the aftermath of Garth’s death — so unexpected, both of them so young; and so rapid, just months after they’d realized anything was wrong — that Cele had first had the thought to give a building, to try to somehow stick things back in place.

“Like?” Cele prompted Sam, when she couldn’t wait anymore.

“Like the building soaks it up.”

So it seemed the buildings had gone one step farther than merely assuming the role she’d envisioned for them. They were taking in life and mess as ballast, affixing themselves. Here was some understanding, instead of just that faint itch from before, though the understanding felt like something pulled from her sleeping mind. It made sense to her in the same way her dreams did.

Cele’s heart pounded. She raised her eyebrows politely. “I imagine you just don’t know your own efficacy, Sam.”

In these forty years since, mud, dirt, and dust had continued to vanish, when no one was looking, from the hallways of Cele’s buildings. Graffiti continued to disappear from the walls of their bathrooms — the more embarrassing its message, the faster it went. What was more, none of her buildings had ever needed painting, or new roofs, or their brick walls re-pointed. Cement did not crumble. Furnaces did not break down. Middlefordians assumed Cele had these matters taken care of while they slept. It did not seem beyond her.

Cele herself had never gained a clearer sense of how it worked — what was even working. Mostly, she kept this lack of knowledge a secret from herself.

If only she’d gotten to the elementary school a little earlier. The existing building, which dated from the twenties, was slated for demolition, a new building to be given next year. In one of her buildings, Cele was sure, this could never, ever have happened.

The elementary-school assistant principal nearly hyper-ventilated as he drove them down Main Street, talking rapidly and senselessly. Cele patted her knees and tried to remember his name. John? Jim? The horror of the moment, of course, but even so she couldn’t ask. She was seventy now, and she was careful with herself in a way she hadn’t bothered with at forty, keeping her gray hair trimmed blunt and precise as the edge of a paintbrush just below her ears, asking only the kinds of questions that betrayed no confusion.

John-Jim was too red where he’d been too pale before. Flooded with blood. Blood-flooded.

“You have to tell them,” John-Jim was saying.

Cele blinked. “Who?”

“The families.”

“What do you mean?”

“I just told you,” he said, though that was a thing people did not say to Cele, people just repeated, if she wanted them to. “Some of the families are at the police station, the ones who can’t find their kids, not outside the school, not at the hospital, and no one will tell them anything.”

“Well, the police should tell them.”

“They will, once they know who exactly, once they’ve handled…” He blanched again. She willed him not to say it, and knew they were all right when he turned back to red. “The police won’t say anything yet, just keep telling them to stay put, and everyone keeps asking and asking, and I don’t know what to say to them. I thought you might. You were who I thought of.”

Of course she was. Who else? Officially, Cele had no real role in Middleford, was nothing more than a donor, but all Middlefordians knew that titles and actualities were not the same. She’d appeared next to Cal Tompkins at his campaign events, when he was running for First Selectman, and he won in a landslide. Zoning changes, tax increases, plans for new parks required her approval. When Jenny Long, local mother, was dying of ovarian cancer, Cele went to visit her every Thursday, and held a fundraiser that produced more money than Jenny had been able to use.

But what did John-Jim expect her to say, once he brought her to this room in the police station where the families were gathered? It would be a small room, without enough chairs, she imagined. What could she possibly say, inside it?

Cele’s cell phone rang. “Cele, is it true?” Kaitlin’s voice, on the line, wavered and caught odd emphases, as if someone were turning the volume on Cele’s phone up and down.

“I think so,” Cele said, because somehow it seemed kinder than just saying yes.

“How can it be? All those kids? All of them?”

Cele pictured Kaitlin hunched over her kitchen table, leaning her rib cage into the wood so the mound of her pregnant stomach could expand beneath. Pressing her palms to that mound, herself and not herself, like a diviner. “Kaitlin, go back to bed,” Cele said, firmly enough that maybe she would listen, and hung up. She wanted to imagine Kaitlin snug beneath her quilt.

John-Jim was still talking, maybe had talked right through the phone call. “You have to tell them something. You’ll know how to do it.”

Crisply, Cele said, “Let me off here, please.”

John-Jim pulled to the side of the road with the automatic obedience that would have returned him to his seat, in school, when instructed. “Here? Why? Please. Please, Mrs. Bailey.”

“I have something I need to take care of.”

“But — ”

She waved a brisk hand and opened the door, a trembling escapee. “Thank you,” she said. Shut the door hard, strode away, leaving him no choice, she thought, but to begin driving, though she didn’t risk turning her head to see.

The town hall loomed before her. No one would look for her here, not for a while. No one would find her and bring her to those families and make her talk to them. Town offices opened at 9:30 and so the door was still locked, but Cele produced her key chain, choking with all the keys to all her doors, from her handbag.

The air inside had its usual marvelous past-scent, marbly and cured. The quiet was another time’s quiet. She breathed it greedily.

Cele knew that Marcia, the town clerk, kept Middleford High School yearbooks in chronological order on a bookshelf in the office on the second floor. Our kids are the heart of this town, Marcia said.

A sophomore last year, not enrolled this year, the assistant principal had told Cele. The name was familiar. His parents she could see in her mind, hazy but there: the father was bald and quiet, the mother brown-haired, with a frequent laugh. But she couldn’t picture the boy, and his faceless name burrowed and chewed. Not that Cele thought she knew every person in Middleford, but she’d thought she knew the ones who might need various kinds of watching. Not to have known this boy — not to have sensed what was lurking, coiling, readying — was a failing, indicative of larger failings.

Cele took the stairs and opened Marcia’s office with another key. There was the yearbook, last in line. Heavy in her hands. She could not open it, but she couldn’t leave it either, so she took it with her down the hall to the Meeting Room, which was Cele’s own understanding of Middleford’s heart. She came here, sometimes, when she had decisions to make. Forty years ago, it had been the first room she envisioned. The first room of her first building: ceremonial, with a somber lacquer, a place for battle-time strategies. She’d known by then that battles could happen when they were least expected.

She set the yearbook on the rich dark wood table at the center of the room and sat down before it. From the walls, portraits of the town’s founders gazed down, peering at the book or at their own reflections in the table’s surface. All of Middleford’s legends. Where no portrait had existed, and no likeness on which a portrait might be based — many of these people were historically significant only in the most local sense — Cele had commissioned artists to make them up wholesale, so that Middlefordians could have faces to put with the names they knew. Sometimes, when she came in here, she even talked to the founders’ portraits. The weight of their gazes helped her hear her own words differently and know what to do.

Cele let herself lay her cheek on the table for a moment. Then she opened the yearbook.

In his picture, the boy looked already dead. Maybe her knowledge was coloring him, but Cele thought he would have looked that way to her yesterday too. The strange pale thinness of the face, as if the flesh were falling away. The eyes canted slightly to the side, looking at what came next. He hadn’t been there, not really. Already he’d been beyond touching.

To leave him that way was more than Cele could bear. She pulled a pen from her handbag, detached the cap with a crisp pop, and then her hand became a child-hand and crab-scribbled out the boy’s face, plaguing him with a swirling cloud of ink, like a rough rendering of dirt or a swarm of insects.

She dropped the pen. She felt the portraits watching her and looked up.

Such histrionics, said the piggy eyes of Richard Stanley, gentleman apple farmer, first to call Middleford a town back in 1723, and who had cared enough to argue with him?

Emmeline Lewis, 1940s Middleford schoolteacher, spectacles aglint: Is it the picture’s fault?

Cele’s own father, his jowly, hairless head sculptural, mythic: You know whose fault it is.

Garth was last in line, there at all only because Cele had insisted. He gazed at her gently and sadly. You know.

A gulping sob ached up Cele’s throat and made a soft, low note. She closed the yearbook and shoved it. It zipped across the tabletop that never in this town hall, in this town, would need polishing. She grabbed her keys and shuffled out, slamming the door behind her and locking it. In the bathroom she vomited up her coffee and flushed away the stinging brown.

She quivered, but she felt calmer. The yearbook should be returned to its line. She could do that, at least.

When she opened the door, the book was no longer on the table.

It must have slipped right off the opposite edge. She went to check, though she knew already that it hadn’t, because she’d seen it in the middle of the tabletop as she ed. The floor was bare but for the chairs’ feet, shaped like lions’ paws.

A book, something so large and substantial as a book, she would not have believed. This room, it seemed, could take in a different kind of disarray. Maybe that was what had been happening all those times she’d come here with half-thought-out plans, and said them out loud, and found her thinking suddenly clearer. Or maybe this was a new gift, for today.

She leaned out the Meeting Room door, listening carefully. Nothing stirred. Nothing would stir. The news must have spread by now, and the people who normally reported here to run the sleepy town offices would be at the police station instead, trying to sort out what they were supposed to do.

She stepped back and surveyed the room, asking it a question. The portraits wouldn’t meet her eyes.

Then Cele heard stirring, after all. Someone calling “Mrs. Bailey?” and footsteps coming up the stairs. She emerged to find John-Jim panting his way toward her. Cele must have left the front door unlocked. She wasn’t the first to forget, today, to lock a door.

“Here you are,” he said. “I drove around so you’d have some time. But now you’re finished. You are, right? And I can bring you.”

Some sickened piece of Cele seemed to have vanished with the yearbook, and she was able to see John-Jim clearly, the whole shaking mess of him. The way a person treading water, breathing deeply, head well clear of the surface, can see every thrash of a distant person as he drowns.

“Are you all right?” she asked.

His face crumpled.

“I saw it,” he blurted. “I heard the noise. I went to check what it was. The whole thing, I saw it, through the door.”

Cele understood. For the rest of his life, he would know himself to be the person who had seen it happen without somehow stopping it (certainly he couldn’t have, but that didn’t matter) — just as Cele would know herself to be the person who had not replaced the elementary school in time.

She was able to see, though, whose knowledge was worse.

Behind her, the portraits whispered. The sound gathered texture in her mind. What she did next came from the same sort of instinct that would have led her to cover up a wound — so it could heal, and because it hurt to look at it.

Cele put her hand on the assistant principal’s plump elbow. “James,” she said, for of course the man’s name was James, how could she ever have forgotten? “Come with me.”

She showed him to a seat at the table. “Wait here. Just for a minute. I’ll be right back.”

Cele closed the door behind her, and locked it. James might or might not have heard the click — it was a quiet lock. She went back to the bathroom and combed her hair into place with her fingers. She looked like herself in the mirror.

When she unlocked and opened the door to the Meeting Room, it was empty, though the chair in which James the assistant principal had been sitting was pushed back from the table just slightly, as if he’d gotten up in a hurry to go wherever he’d gone.

Cele talked to people all day long. To the police, to the various reporters who arrived so quickly it seemed they must have scented the event before it actually happened, to members of the school board. To the families. She didn’t cry. To cry would be disrespectful — what would it leave for the others to do, with so much more to grieve than she had? Expression had a ceiling whose height must be considered, and where one’s claim lay beneath it.

“Where did James go?” said the raw-nosed, weeping elementary-school principal, Heidi Watkins. Heidi had seen nothing. By the time she came out of her office it was all finished.

“I have no idea,” Cele told her, not untruthfully.

Cele had Mark Barrows from the police department drive her home, long after dark. Instead of taking the trim path to her own front steps she turned toward Kaitlin’s house.

Andrew answered the door. “Oh, thank God,” he said, without any of his habitual charming irony. There was a crease down the middle of one of his freckled cheeks, as if he’d been recently in bed. Cele’s feelings about Andrew in general were mild, benevolent: he was no worse than anyone would have been. Today she felt grateful he’d been home with Kaitlin all day. She followed him back to where Kaitlin sat, tucked into a corner of the couch, her belly like a pillow she’d positioned herself behind for security, staring at the television.

“They aren’t really saying anything new,” Kaitlin said. Cele sat down beside her, and Andrew ducked out again.

“They must have already said what they know,” Cele told her.

“So what do you know?” Kaitlin turned to face Cele. Always that sharpness to her. It was what made seeing her round in pregnancy so odd — a globe strapped to a collection of angles.

Kaitlin’s parents had lived in this house for years, and had begun raising Kaitlin’s older brothers and then Kaitlin herself here, before Cele really noticed any of them. Then one Halloween she’d answered a knock at her door to find Kaitlin, who was then about six, in a Dorothy costume on the stoop with her two older brothers, both attired as Star Wars Stormtroopers. Cele had turned fifty that year, and all evening as she’d bestowed candy on neighborhood children, she’d been dogged by a sudden understanding that if these children discussed her after, they would call her the old woman.

“You didn’t want to be Princess Leia?” she asked Kaitlin.

“I’m Dorothy every year.”

“Why?”

“Knowing ahead of time makes everybody feel good.”

The two brothers were jostling over Cele’s candy bar selection. Cele peered at the little girl in her wig with its brown braids, a loop of her real, blond hair caught in the band at the forehead.

“What a good thing to have realized,” Cele told her.

After that Kaitlin came often to Cele’s house to drink juice at the dining room table, dipping her beaky little nose into her cup with each sip and telling Cele about her brothers and teachers and friends and parents. Cele sometimes played a private game while Kaitlin talked, pretending Kaitlin was her child, hers and Garth’s. Any child they’d actually had would have been grown by then, of course, but it was just a game.

When Kaitlin went away to college, Cele thought she’d lost her. As it turned out, Kaitlin had only found Andrew and brought him back here, where she took a job teaching fifth grade at Middleford Elementary. “Middleford just feels more real than other places,” she’d told Cele.

“Yes,” Cele had said, thinking of all the bricks she’d piled. But Kaitlin had never shown any sign of suspecting the bricks’ role. To her, it seemed, Middleford’s stability was simply one of its features, like the sharp curve on Main Street, or the tea-colored, leaf-clogged pond at the north edge of town.

Once Kaitlin began spending her days at the elementary school, Cele had wanted to bump up its replacing in her plans. But the original building was still sound enough, and the foundation of the middle school had cracked. To switch the order would have been to make an admission of something.

Now, Cele held Kaitlin’s bony, oddly warm hand. “Well, what have they been saying?” she said, and Kaitlin began to recite the numbers and the names and the sequence of locations — parking lot to front door to classroom, and why weren’t the doors locked? That question again.

“That’s all I know too,” Cele told her. “Nobody knows more than that now.”

“You must.” Kaitlin’s nose ran. She rubbed it angrily.

“It was third grade, Kaitlin. It was far away from your wing,” Cele said.

“I know that.”

If Cele knew what Kaitlin wanted to hear, she’d say it. She was used to understanding Kaitlin, but since Kaitlin’s pregnancy and especially since her maternity leave had begun two weeks earlier, Kaitlin had been saying things Cele couldn’t see to the bottom of. I wish there were a window in my stomach, so I could look at all his parts and organs and everything and make sure it’s all in the right place, she said, making Cele think of cadavers hacked up by medical school students. I wish I knew every thought my son was ever going to have. Cele had never felt that way about another person, not even Garth, whom she’d loved until she felt she was about to split open.

I think having a child is the most terrifying thing a person can ever do to themselves.

“What else do you want to know?” Cele asked.

“I want to know why. I want to know what was wrong with him, that he did this. What his reasons were.”

“The reasons of people like this aren’t reasons. They don’t help anything.”

“It would help me, to know.”

Cele said what would help Kaitlin was going to bed. Bundled her up the stairs. Andrew appeared and watched from the top, and Cele felt better, knowing that Kaitlin only had to traverse the staircase itself alone. Halfway, Kaitlin stopped and turned back.

“Cele,” she asked, “what are those mothers going to do?”

Cele sat in her bedroom that night and held her keys in her lap. She hadn’t been able to leave them downstairs. The weight of them, in the dip between her thighs, pulled the material of her nightgown tight, like somebody’s sleeping hand. Two of the rings held all the keys they could; the last was almost full. If that last ring had been a clock face, the keys took up all the room between ten and two. The key to every door in every building Cele had built was on one of these three rings. Nothing special, in itself, this key chain — just a cracked black plastic fob and the large metal rings — other than the fact that it had been Garth’s, once.

Because the elementary school wasn’t hers yet, Cele had no keys to it. So she couldn’t touch the ones for the front door, the third-grade classroom, and wonder why their corresponding locks had not been thrown that morning. Probably there was no real reason, only that locking them had never been necessary before. Probably it wouldn’t have mattered anyway.

Cele had visited the elementary school along with the other schools this winter, as she did every year. There was no official justification for these visits, of course, but no one was going to tell her she couldn’t. She went because she wanted to watch the children’s faces at the middle school and the high school, looking for signs that they could feel the buildings’ hunger for the gum they stuck under their desks, the crumpled paper that fell short of trash cans, the clumsier of their words. At the elementary school, she laid plans for new classroom spaces as she sat against back walls and listened to lessons. She stayed no longer in Kaitlin’s classroom than in any of the others, just as she’d promised herself ahead of time. But she loved watching Kaitlin at the front of the room, her belly then just visibly swelling, teaching a lesson on The Witch of Blackbird Pond. It seemed exactly the right place, in all the world, for Kaitlin to be.

The elementary-school children, too, had demanded Cele’s attention. They twitched with their wants and fears. Chewing on pencils and fingers, sucking on swatches of their own hair, as if they were trying to take their world inside themselves.

Cele counted her keys now, for the soothingness of it, the way a miser counts coins. Eighty-two. Each key attached to a space she could open at will. Locks mattered. Locks made you owner. Plus, there was all they let you keep in, and out.

Cele wasn’t sure what that meant for James. She had no guesses about where he was now, if he was anywhere. What she’d done was horrible, maybe, except it didn’t feel that way. If she’d known what would happen when she locked him in the Meeting Room, she was almost sure she wouldn’t have been brave enough, though it was true she had never been lacking in bravery. Really, she was sure of nothing except what she’d relieved him of, what his life in Middleford would have been like after this day. She had no means of evaluating the rightness or wrongness of closing that door, turning that lock, but at least it was a decision, a shaping. Better, perhaps, than the formlessness of accident — a forgotten lock, or two, the imbalances of one boy, a rogue and energetic cell in the bloodstream — reverberating and knocking things down.

The new elementary school would come with maybe twenty-five keys, all told. Cele closed her eyes, pinched the pads of her fingers together, and imagined those keys between them, each jagged tooth. But she couldn’t seem to give them the weight of metal in her mind. They stayed light as toothpicks, light as fingernails, light as hair.

The reporters settled in and got comfortable. Their stories in print and on television made Cele ill — they used quaint postcard-like pictures of Middleford that they’d tinted gray, and horror-movie music hummed in all their prose. To discover more about the young man, they talked to his three-doors-down neighbor, and trumpet teacher, and dentist, and former classmate. Watery collages of details about the children and their teacher were assembled. Cele unplugged her television and threw away her newspapers still in their bags.

Schools stayed closed, all that week and into the next. The streets were empty of Middlefordians but chock-full of rubberneckers from near and far. On her way to buy groceries, Cele was tempted to run down with her car a pair of middle-aged women, pointing and clutching each other on the street, cheeks rouged by titillation.

Garth had always told Cele she was ruthless. He said it with warmth but also with wonder. Somehow he’d spied this sort of impulse in her, even then.

James’s family seemed only a little concerned about where he had gone. Cele took this impossibility for a reassuring sign, a demonstration of rightness, like the failure of anyone in town to ever demand an explanation for her buildings’ strange self-repair. James’s wife told somebody James must be clearing his head, and that was the explanation that circulated. The question of his current location seemed papered over: there, and everyone knew it, but nobody looked at it. He’d become part of the anchoring, maybe, Cele thought, which they all needed more than ever. Part of what the buildings sucked in to keep this town in place.

Meanwhile, Kaitlin stopped brushing her hair, allowing it to become a pale knotty cloud. She wore the same black sweatpants and T-shirt every day and began to take on the smell of overripe fruit. Andrew had gone back to work, and Cele thought it might have been better in some ways if Kaitlin could have returned to teaching; the children would have asked questions, and made mistakes, and dropped things, and stopped seeming like symbols of anything. But of course the school wasn’t even open. Cele adopted the routine she’d imagined for a month from now, after the baby was born, having Chinese food delivered to Kaitlin and Andrew’s, or stopping by to make coffee. Their house seemed so quiet, quieter somehow than Cele’s own.

“Cele, what do you remember about Sonya Cummings?” Kaitlin asked, one rainy Thursday.

“You worked down the hall from her. You don’t need me to remember her for you.”

“When she was a kid, I meant.”

Cele considered. In her mind, she stripped Sonya’s face of its middle-aged fleshiness. “She was noisy. That’s probably not surprising. She loved jump rope, I think.”

Kaitlin chewed on her lips. “She always sounded like she was reading Hallmark cards. I keep trying to imagine what she’d have said about this.”

“There isn’t a card for this,” Cele said.

Kaitlin waddled to the sink and banged her tea mug down inside, hard enough to rattle the spoon. “Jump rope? I can’t picture that at all.”

“Well, she was smaller then.”

When Kaitlin turned around, she’d lifted the spoon from the cup, and she brandished it at Cele. “I don’t think,” she said, “I want this baby to be born.”

“Of course you do,” Cele said briskly. But she was seeing her buildings bulging, their seams stretching, thinking how it would be if everything they’d kept safe and hidden inside were about to burst forth. Her knees trembled.

Kaitlin threw the spoon. It sounded much larger than it was, hitting the floor.

“Cele, why didn’t you build a new elementary school?” she said, and Cele was surprised enough that she had to sit down. Kaitlin sat, too. She watched Cele, who had no answer for her.

After a moment, Cele stood and picked up the thrown spoon. She washed it carefully, running her thumb along its rim. Dried it and put it silently back in its drawer.

The next day, Cele decided on gardening. She would plant hardy early-spring flowers so Kaitlin could see some color when she looked out the window. If she seemed to notice, Cele would plant some at her house too.

Cele’s legs didn’t like folding up so she could kneel on the ground — when had that happened, that they’d stopped listening to her without complaint? — but her fingers bent easily, dug easily. She enjoyed the feel of the soil. Cool and moist, like touching the deepest dark. She made holes for the pink and purple pansies and wondered about herself, whether her legs or her fingers foretold her future. Part of her was still sure she would turn out to be like her buildings. In two hundred years she would still be a fixture, and no one would quite know how old she was, and new Middlefordians would still be allowing her to stow them away in safe compartments. The prospect made her tired.

Astonishing, that Kaitlin should know about the buildings. Maybe the knowledge had just then risen up from Kaitlin’s depths like a bubble. Or maybe she’d known all along and never said a word.

The first pansy Cele planted settled perfectly straight. She tucked a mound of dirt around the roots, patted it firm.

When she turned to reach for the next, she found that the mothers were coming up her walkway.

A pack of them. A tribe of grief. Ella McIntyre, who’d cried loudest of any at the police station, led the way. They stopped, their toes at the edge of the at of pansies.

“What can you do for us?” Ella said to Cele.

“I’m sorry?”

“What can you do?” the blond Perkins mother said. Cele had never known her first name.

Why the mothers had come this way, all together, Cele had no idea. Perhaps the fathers would come up her path tomorrow, or next month, and then the grandmothers, and the grandfathers, and the siblings.

But the mothers were here now, waiting for their answer. Cele could tell them there was nothing. They’d have to believe her. Who do you think I am? she could say.

The mothers had white, nervous fingers. They had dry, blasted eyes. Their feet shuffled in place. From some things, Cele thought, there was no recovering. She should know — Garth’s death had been that, almost, for her. To turn it into only almost, to give herself enough heft to keep from floating away, she’d had to weigh down all of Middleford. There wasn’t enough space on the whole surface of the earth to build what it would take to reach these mothers. Their pain was a vast, unchartable, unimaginable sea. Cele couldn’t see its edges. She wasn’t sure it had any, but if it did, they were beyond the reach of her mind, and beyond the reach of the mothers’ minds too.

Well, what, then? People lived with unlivable things all the time. There was no rule that Cele had to watch them try.

Cele looked up at them, right into all those faces. Rules, though, had never had much to do with the actual shape of Cele’s life. These women weren’t Cele’s responsibility, except that she’d decided long ago they all were.

“Come with me,” Cele told them.

She led the silent line of mothers to the town hall. She could feel them behind her, like a black held breath. They were suspended, all of them, in the same moment, though it would look different to each. An orange backpack, a crooked braid, new nail polish, a tooth lost the night before. The way their treasure had looked the last time they’d seen it. None of these women was ever getting out of this moment, and it was too much to expect them to drag it around with them through the rest of their slow, slow lives. Cele felt sure that whatever she was bringing them to must be better than that. She imagined it as a long white room full of narrow beds with crisp sheets. They would each get in, and lay the black- ness down, and rest their eyes on a white ceiling.

The Meeting Room seemed to sigh as the mothers entered. They took their places around the table. They planted their elbows on the wood, leaned their heads into their hands. Some of them closed their eyes.

“Just a moment. I’ll be right back,” Cele told them. She closed and locked the door.

One of the fathers was interviewed on television, a few days later. Cele, who’d plugged her TV in again, watched him speak. “I think she just went off somewhere,” the father said. “I think she needed to.”

The mothers had gone off. James was clearing his head. The caretakers Cele hired were unusually strong and efficient men, especially given their age. Vast soundless hands placed new roofs, when needed, in the middle of the night. These stories were Cele’s gift to Middleford; something, if not as much as she would have liked.

Cele jingled her keys. She carried them everywhere with her now.

When Cele brought over a pizza the following week, Andrew met her at the door. He tugged Cele into the coat closet. “She isn’t getting better,” he said. “Everybody else is getting better.”

If Garth had been able to see what happened to Cele after he died, he would not have thought her ruthless. She stopped getting out of bed. It had soothed her to fold the blanket in a certain fashion: lying down, she would make a pleat at the top edge, then double it over, again, again, until it was thigh-level and she would have had to sit up to keep folding. Then she unfolded, up and up, tucking herself back in. Then she started over. She spent whole days doing that. In a different version of her life, she might have spent whole years. Garth would have been terrified, watching her drift, and he would have tried and tried to throw her lines. She was grateful she hadn’t ever had to see Garth look the way Andrew looked just now.

Eventually, Cele swam back in. She couldn’t quite remember why, or how. One day she got up instead of staying in bed, and the rest followed. This time she just had to tow Kaitlin with her, that was all. Kaitlin was not like the mothers, or James — she could not be that far out. There was no reason for her to be that far. Cele would bring her back in.

Cele put a hand on Andrew’s shoulder and used a muted version of her bullhorn voice, the one from her ribbon-cutting ceremonies. “Kaitlin will be fine, Andrew.”

“I hope so,” Andrew said.

After Kaitlin had eaten a piece of the pizza, Cele draped her in a sweater and brought her to see the pansies. The cardigan hung like open curtains, unable to button over Kaitlin’s stomach.

The flowers were taking, and they nodded their cheerful heads. Kaitlin stooped as if to smell them. Then she began ripping them up.

When she’d finished, when all the pansies lay limp on the grass, Kaitlin said to Cele, “Please.”

“Please what? What do you want me to do?” Cele asked. “Just tell me.”

“Wherever you took the others,” Kaitlin said. “Take me.”

Cele was willing to swim with Kaitlin forever, pull and pull, but she hadn’t thought to ask Kaitlin if the pulling hurt. Because it wasn’t just Kaitlin, after all. Kaitlin had to pull somebody else with her. Extra drag. Cele hadn’t thought of that. How could she have? How could she know what that felt like?

“I’ll just show you,” Cele said. “I’ll show you and you can decide.”

Cele drove Kaitlin to the town hall. It was too far for Kaitlin to walk, now that she was so big. Carefully, she shepherded Kaitlin toward the Meeting Room, hand on Kaitlin’s shoulder as she climbed the stairs. They stood together outside the door while Cele grabbed for the keys in her purse, fumbled them, grabbed again.

“Easy,” she said, mostly to herself.

“Easy-peasy,” Kaitlin said absently.

Cele turned. Kaitlin held the small of her own back, eagerly watching the door, as if behind it were nectar or balm. Cele didn’t think that was wrong, exactly. Still, there was Kaitlin’s face, the precious warm fact of it. She touched Kaitlin’s smooth cheek, and Kaitlin’s eyes darted to Cele’s face, then back to the door again.

She would only be giving Kaitlin a choice, but she didn’t want Kaitlin to have this choice. Did not want the possibility of having to close this door on her, having to stand outside and fit the key to the lock and turn. Why should Cele have to be the one to do it, over and over again?

Cele asked Kaitlin to sit on the stairs. “There’s something I need to check inside,” she said.

Kaitlin sat down, off-balance, front-heavy.

“Be careful,” Cele told her.

Cele went in and closed the door. She twisted the lock so Kaitlin wouldn’t come in. She thought about whoever had been the last person into the elementary school that morning, and of Sonya Cummings inside her third-grade classroom, both of them closing doors and stopping short of this one last movement.

Cele walked to the head of the table and set down her keys. She kept her eyes on the shine of them against the wood and tried to make her voice as strong as it had been when she’d come into this room to talk over other decisions, over the years, back when she had thought she was talking only to herself. “I don’t want these. I don’t want to do it anymore,” she said. She felt so light without the keys in her hand.

That isn’t all you’ve brought us.

She looked up. At the end of the row, beside Garth, was the yearbook photo of the boy with his scribbled-out face. Large as the others, framed like the others. Through the ink she could still make out his features.

“Not you,” she said.

Garth’s eyes sparkled. All their eyes sparkled. Wet, deep as small seas, then not small, widening. Cele looked back at the door, the lock on the door, which she herself had thrown.