Interviews

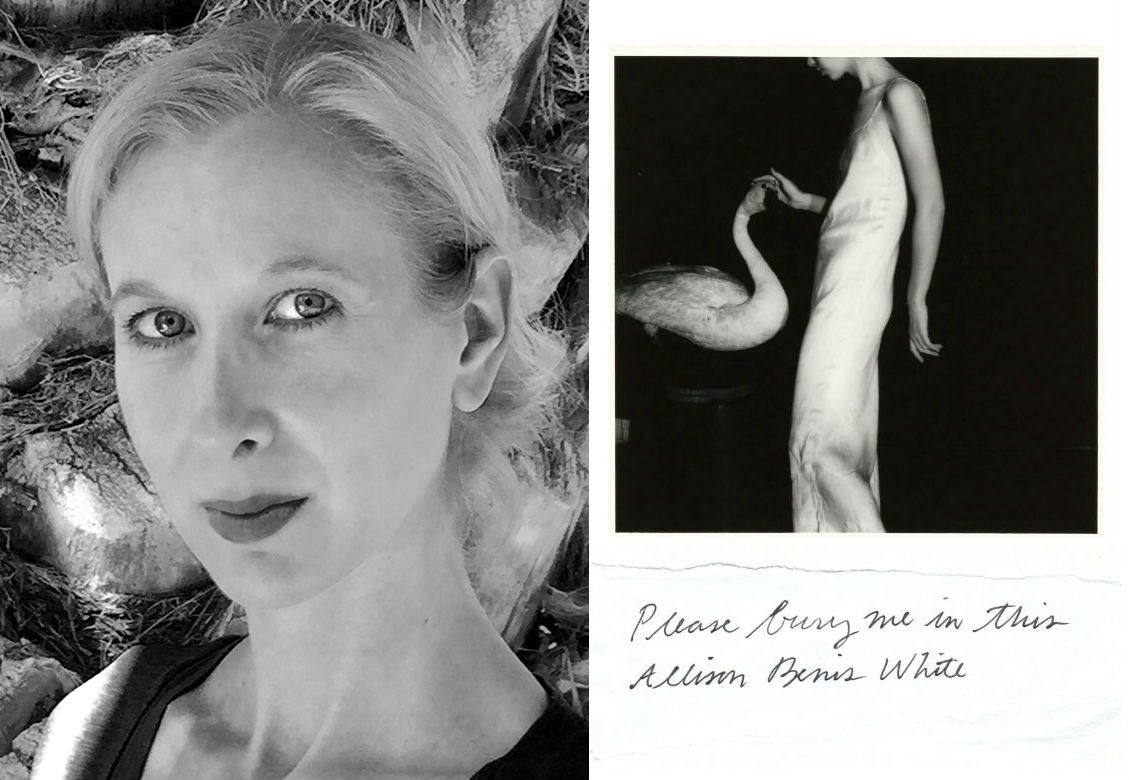

Allison Benis White’s Poetry Will Gut You

Benis White on suicide contagion, the limits of language, and her powerful new collection, ‘Please Bury Me in This’

I sometimes worry that there will come a point in my reading life where I won’t be able to have the kind of visceral, unmanageable reaction to a book that I’ve often felt was made possible by my being young, hypersensitive, and — frankly — unmedicated. I worry that it’s behind me now, the time where I can be positively torn asunder by a text the way that I was when I read Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation at sixteen, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway at eighteen, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets at twenty-one. I never have the opportunity to worry about this for very long, however, because invariably what happens is that a book will land in my lap that proves I’m still (and hopefully always) alive and vulnerable to language, wielded expertly, which brings into being new, singular cartographies of emotional landscapes.

Allison Benis White’s Please Bury Me in This is such a book. Its effect in my first reading cannot be overstated. I texted a photo of a page — of which I’d highlighted the entirety — to a friend and wrote, simply, “I’m gutted.”

As is the nature of anything sublime, White’s collection of poems combats easy synopsis or concise abbreviation. I’m inclined to call them elegies of a sort, if, as Mary Jo Bang suggests, we understand that the objective of an elegy is “to rebreathe life into what the gone once was.” But the elegy that extends throughout Please Bury Me in This is as much about the haunting insufficiency of language as it is about the cruelty and greed of time and the disunity with which it can frame one’s life. White’s poems have no interest in ribbon-tying or putting everything in its right place. There are no bright, right places — that is grief. The beauty and the power of these poems, then, lies in the acknowledgement of this and the persistence to search anyhow; a gesturing, a reaching toward, that constitutes its own species of expression; its own grammar of grief.

It was so gratifying — and not a little emotional — to speak with White by email about Please Bury Me in This, out March 7th from Four Way Books.

Vincent Scarpa: The epigraph for the book comes from an article that appeared in The New York Times in 2014: “Mental illness is not a communicable disease, but there is a strong body of evidence that suicide is still contagious.” I thought the best way to open up a discussion of the book might be to ask what led you to situate this as the epigraph? It seems multivalent, multipurpose — both the placement and the sentence itself. I suppose this is also a question about intention on a larger scale, too. Was there something specific that set these poems into motion and found them cohering into a collection?

Allison Benis White: Yes, the epigraph refers to something specific that set these poems in motion — well, two specific events, both of which are gestured to in the dedications: “For the four women I knew who took their lives within a year” and “For my father.” After a very dear friend committed suicide, three more women (who were in our close and extended group of friends) took their lives as well — one every three months for a year. Each suicide was in some way a reaction to the previous suicide(s) — and this epigraph about suicide contagion was a succinct way to situate the poems’ originating traumas, and to locate the speaker as a potential victim of this contagion. My father’s death was also an originating event for these poems and is, more subtly, folded into the epigraph, as he suffered from significant mental illness, although his death was natural.

VS: Rachel Syme wrote a very interesting piece recently in The New Republic; a review of Sarah Manguso’s 300 Arguments that placed the book in a lineage of “many short, intensely personal works by women that have in recent years blurred the boundaries between poetry and prose.” As I told you before we started this interview, I place Please Bury Me in This on the same shelf as some of my all-time favorite books — Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, Rebecca Reilly’s Repetition, Jennifer Denrow’s California, Jenny Boully’s one love affair — because I found this collection as vulnerable and stunning and precise as those books in the way it maps the tectonic shifts of feeling and thought. The question of lineage, though, or the fact that these “intensely personal works” were all written by women and were all, to some extent, fragmentary/genre-blurring in nature, hadn’t really occurred to me — or, it hadn’t occurred to me as especially notable — until reading Syme’s piece. She says, “These are expansive narratives, but ones that take place inside compact vessels. It is as if these writers feel they need to pack as much into as little space as possible…and attempt to infuse it with a new resonance and weirdness, with something human and desperate.” I’d be interested in hearing you ricochet off of this — the possibility of there being a kind of reticulum between gender, genre, form, and content — in whatever way you feel compelled. All I could land on with any lucidity in my own thought process, particular to your book, is that the fragmented form can be a machine of meaning-making by virtue of the fact that it dramatizes isolation both in content and on the page itself, cut through with white space, and it dramatizes the fraught nature of connection as it arranges some lines to feel linked to what come before or after them and others to stand utterly loose, unstabled.

ABW: Wow, what a gorgeous analysis — what gorgeous insights. My instinct is to just let your words stand and not poison them with my own. But this is an interview (!), so I’ll try and say a few things. First, I’m in love with all the books you mentioned (bar the recent Manguso, which I haven’t had the chance to read yet), and I’m honored to be in their company. Each one of these books has paved the way for my act of articulation in Please Bury Me in This. I can say, on the page, I’m interested in violently but carefully carving away the unnecessary in an effort to access essential heat. I’m also obsessively interested in the virtue of “lightness” on the page, as Italo Calvino describes so beautifully in his first essay in Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Ultimately, I think form is emotional and intuitive. At one point, in a poem toward the end of the book, I wrote, “I mean the sentences cannot touch.” And I was like, oh, O.K., that’s what’s been going on this whole time: a kind of necessary isolation and illumination of (white) space via a series of double-spaced sentences as a means to represent the speaker’s fraught aloneness/weirdness and need to connect/gather. In the same poem, the line “…so the emptiness can pass through” arose. This seemed to communicate (to me) the goal of the form as well: to create space for passage — a cage for release.

VS: As I was reading and then rereading, I wondered whether it came about naturally in drafting or if it was perhaps more purposeful, your inviting certain figures — Woolf, Sexton, Plath, Duras — to be something like interlocutors in the text. At certain moments, you’re using their words directly, but at others you seem to be almost addressing them, or speaking from a locus that their work has opened up for you. Can you talk about the process by which these and other women — Lispector, Dickinson, Stein, O’Keeffe — made their way into the body of Please Bury Me in This?

ABW: I think the process was both natural and purposeful — natural in that these women, these minds, (what I call “my good voices”) are the ones I keep open on my desk while I write, the minds I want/need to be in conversation with. And purposeful in that I don’t want to be (and terribly want to be) alone. Employing their words periodically, and speaking to them (or near them), is an act of (or gesture toward) communion. I want to be with them (as well as with my dead friends), and so I’ve made a room, several rooms, in which to safely do that.

VS: The collection has a number of interests, but chief among them — in my reading, anyway — seemed to be the (in)sufficiency of language as a conduit for expressing/communicating experience — specifically, the experiences of grief and of suffering, emotional or physical. This is an area in which I’ve always been interested and which I, too, have written about, so it’s unsurprisingly one of the elements of Please Bury Me in This that most activated me emotionally and intellectually. Throughout the collection are moments where you touch down on this. In one poem you write, “I want a larger cage: every page, every letter;” a kind of acknowledgement that language is inherently an immuring agent, but that one can still state the desire, through language, for an increase in its capacity. (And perhaps that, in and of itself, is an enlargement!) I wonder if you could talk a bit about this, specific to what your vision for Please Bury Me in This was at the start and then the architecting of it with, as you say, “these words, their spectacular lack.”

ABW: Well, this is everything, isn’t it? — the need to use language on the page (because I can’t paint or sing, which will never cease to disappoint me — although I can dance (!), but not well enough to meet my needs to convey/invent) and the inherent failure of language to communicate trauma (the unsayable). This tension is the nexus: the only way I can scratch toward articulation is to begin with an admission of failure. This act of telling the truth (to myself) allows me to persist. Language cannot resolve grief or contain it, but it can sometimes make a box (a poem, a book) within which something alive (heat-producing) can be experienced.

VS: Following that thread a bit further, I wonder what your thoughts are now, having finished the book, about moments in the text wherein you seem to be flagging a failure of language, of communication, of writing, especially as it pertains to addressing another. “I am not any closer to saying what I mean,” you write in one poem. “Someday I believe, in order to be free, what I say will trample me,” you write in another. And then, on the penultimate page, in a particularly wrenching moment in a book unsparingly replete with them, you write, “I am writing to you as an act of ending.” I love that line so much for its choice not to designate what the speaker aims to end, only that she aims to end something via the act of writing. I’m not interested in — I’m not asking about — the question of whether or not writing is cathartic. (A question to which, it has always seemed to me, there’s exactly one honest, unsatisfactory answer: only so much and no more.) Rather, I guess I wonder what you feel you’ve ended — if you feel, even — with writing and now publishing Please Bury Me in This, which you dedicate to four women you’ve lost to suicide and to your father. Do you feel closer to having said what you meant? Or is the best one can hope for something like the effect you describe when you write, “What makes the shape become visible, and breathe, is the angle and variation of absence”?

ABW: I have three immediate responses to these questions: 1) Can I please steal your line and someday title a book, Only So Much and No More — or will you please write a book with that tile? 2) At this moment, I only know/feel that I’ve ended writing Please Bury Me in This, and 3) I suspect I may be closer to having said what I meant based on this series of interview questions.

VS: Oh, that’s happy-making to hear! And yes, the title is all yours.

My final question, fittingly, has to do with a line on the final page: “I mean the death of death leaves a hole.” That line was like an apple corer to my heart. And it reminded me of a line from Amy Hempel’s story “Beg, Sl Tog, Inc, Cont, Rep”: “The worst of it is over now, and I can’t say that I am glad. Lose that sense of loss — you have gone and lost something else.” Something essential, yet almost incommunicable, is being pointed to in both. Not that one would necessarily want to treasure or cling to one’s pain or angst or grief — though I think it’s quite common, and not at all inexplicable — but that it becomes familiar, and there is a manner of comfort in the familiar, and the pain can come to calibrate you, even dictate a sense of purpose. It can, as you write, “assemble the soul.” Having had the last word — at least, the last word in this book — on the set of concerns and emotional territory which, I can only assume, were what drove you to write these poems in the first place, I wonder if you feel that hole of “the death of death,” the loss of that sense of loss, and what you do with it. I ask, perhaps, because I’ve recognized in my own writing about pain a certain kind of resistance to completion, fearing what will and will not be on the other side of writing, what wrecked city the pain might leave behind when it leaves.

ABW: These questions are destroying me (in the best way). Will you marry me? Oh wait, I’m already married. OK, that was weird. Bear with me. I’ve been alone with this work for a very long time, and your words are a kind of knowing and understanding that is just brutal. I will just say that after finishing Please Bury Me in This, I wrote another manuscript in a fever (within a year) so as to remain in close proximity to my losses. They’ve piled up in such a way I don’t know who I am without them.