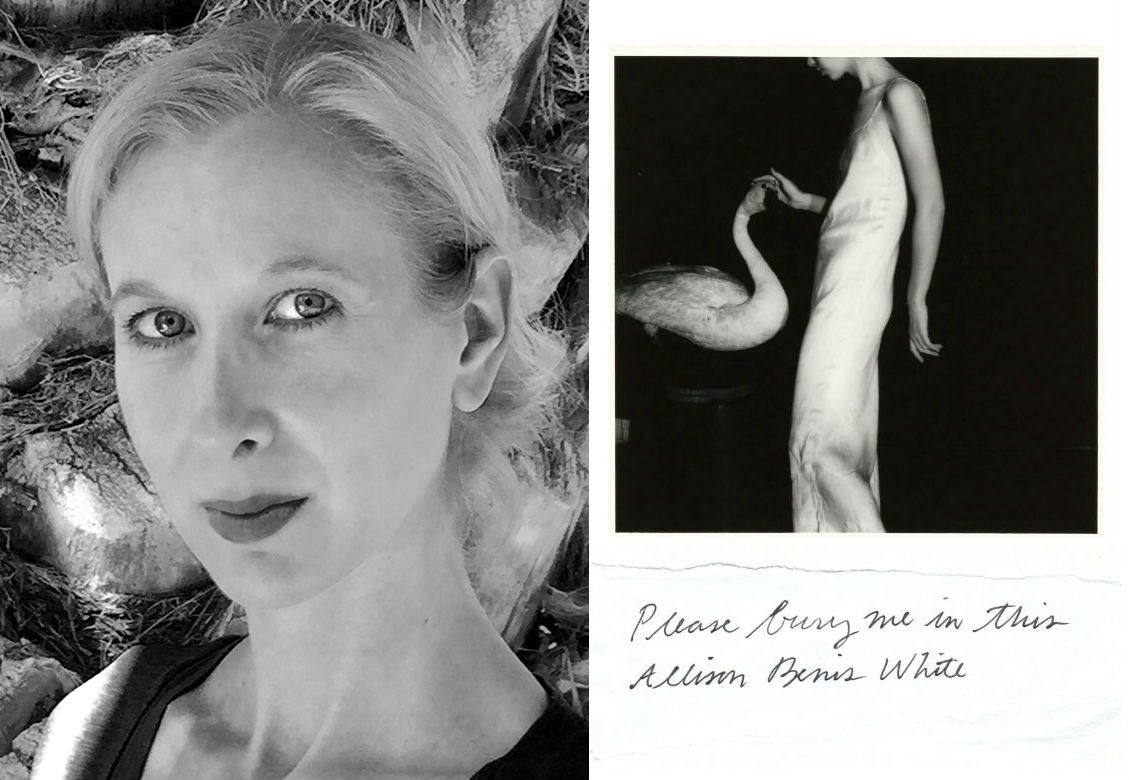

interviews

Kevin Wilson’s Stories Are About the Way We Live with Failure

The author of ‘Baby You’re Gonna Be Mine,’ on the universality of failing

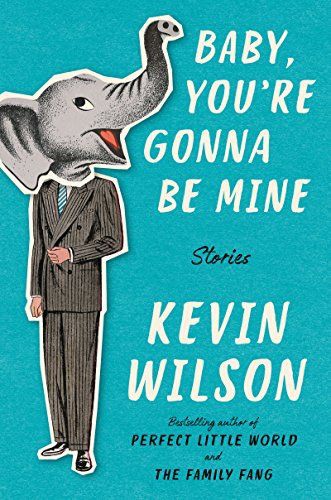

Summoning his classic combination of humor, heart, and quirkiness, Kevin Wilson returns with his latest short story collection, Baby, You’re Gonna Be Mine, his first collection since 2009’s Tunneling to the Center of the Earth.

Baby, You’re Gonna Be Mine finds Wilson exploring the complicated terrain of parent-child relationships, such as is the case in “Sanders for a Night,” which looks at how family members cope with a death, and the title story itself about a young musician who can’t seem to fully embrace the challenges of adulthood. Wilson also dives into the realm of magical realism in the brilliant “Wildfire Johnny.”

No matter the topic, Wilson writes with an authentic voice that captures the truths of the characters he creates.

Bradley Sides: Your work often focuses on the lives of young people — children, teenagers, and young adults. What is it about these young lives that make them such good subjects?

Kevin Wilson: There’s something combustible about any new experience. I’ll always be drawn to my own memories of standing on the precipice of what I believed that my life would become. And how scary that was. And I’m getting older, and maybe I should move on, but now I have kids of my own, and I’m watching them experience these important moments, and it brings it all up again. It’s hard not to put it into my work.

This is slightly beyond this question, but people talk a lot about how resilient children are. I was not a resilient child. At all. And I don’t know that I believe this assertion. I think children aren’t necessarily resilient; I think that their youth, their newness to the world, allows them to pull things inside of them and keep moving, but I don’t think they lose those bad things that happened to them. I don’t think they forget them. I think those traumas attach themselves in weird ways, and it’s only later that we can make sense of them. So I write about those moments, when something life-changing happens, but it’s too fresh for it to be properly observed.

Stories are a kind of incantation. There’s this magic, like I’m trying to tell the story with the aid of only one deep breath.

BS: Oftentimes, these young people are busy disappointing their parents. This sense of disappointment seems to link many of the stories in your collection. Parental disappointment is something most of us experience — either we are disappointing our parents or we’ve been disappointed as parents. Is this theme appealing to you are a writer because it’s such a universal experience? Or is there something else that draws you to it?

KW: Failure is such a constant in life. It’s kind of the only thing. And what I’m interested in is not so much the actual failure but the way we live with the failure, the way we accept how flawed we are and try to move forward, to make a life for ourselves.

BS: “Wildfire Johnny” is brilliant. It has such a balanced feeling to it. It’s fun, but it’s somber. It’s real, but it’s magical. It’s a knockout kind of story. And here’s the premise: a razor blade essentially grants time traveling powers to people who use it. The instructions state, “You may travel twenty-four hours into the past. To do so, simply take the blade and cut open your throat. With one expertly executed slash, you will find yourself twenty-four hours in the past, bearing no signs of the injury, able to undo any forthcoming misfortune. You may travel as many days into the past as you wish, as long as you cut open your throat for each twenty-four-hour interval.” I’m curious about this story’s genesis.

KW: That’s very kind of you to say. It’s a story that I really struggled with, kept thinking about it and putting it away, never quite sure how to manage it.

For the origin, this feels weird to say. I’m trying to decide how to explain it without seeming like a freakish person. More than ten years ago, I saw this French movie, Cache. In it, a man sees another man from his past. They are standing in this apartment, and one of them takes out a razor blade, draws it across his throat, and kills himself. The spray of blood, the suddenness of the act, the way the man who is still alive processes this trauma in the moment, it absolutely wrecked me. I do not honestly remember much else about the movie, how it ends, etc. But I would say that, since I saw it more than ten years ago, that moment vividly flashes in my brain maybe three times a week. It’s this unwanted image that just keeps coming to me again and again. It is very vivid, and it disorients me. And, though this is hard to talk about, there’s something seductive about it, even as it horrifies me. When I get anxious in public, I think about this moment. And eventually, I needed to figure out how to write about it, but it always felt too visceral, too literal. Anyways, I started thinking about how this act could be utilized with the aid of magic. I wanted to let that man live, to bring him back. So I wrote this story. And I tied it up with all these other things. And this is what I have.

I’m interested in the way we live with failure, the way we accept how flawed we are and try to move forward, to make a life for ourselves.

BS: What about “Baby, You’re Gonna Be Mine” led it to be your title story?

KW: For many of the stories, the focus is on the dynamic of parent and child, of being on either side of that equation. “Baby, You’re Gonna Be Mine” seems to fully embody these issues. In this story, the mother has to deal with her memories of her child and how they exist right next to his actual body in her house, since he’s moved back in with her. It must be a strange sensation.

My children are beautiful and sensitive and wonderful. I love them without reservation. But my oldest is ten, and there are ways that I can see him becoming his own person, and those memories I have of him at three years old are already fading, like they’re about a separate person. This makes me both happy and anxious. I know at some point, my sons will leave me behind, will become the people that they want to become. But I’ll keep holding onto them in whatever way that I can. And maybe stories are one way for me to freeze them in my mind.

Kevin Wilson on the Weirdness of Family

BS: You created some dynamic characters in the stories here. There are two I’m thinking about in particular: Adam from “Baby, You’re Gonna Be Mine” and Jackson from “Housewarming.” Both are young men who are struggling to adult. For Adam, he can’t face the reality that his once-moving music career might actually be over. Jackson has a terrible temper and can’t control himself. As difficult as they are to love, I can’t help but root for both of them. What do you hope readers take away from your characters?

KW: I can’t control whether my characters are liked or disliked by the reader, because there are so many factors that complicate that connection. But what I hope that I can do for my characters, because I do feel a need to care for them, is make them understandable to the reader. If I can make them as clear as possible, then I’ve given them a chance. I’ve given them depth, I’ve complicated the initial desire to judge them on the surface. Whatever happens after that is beyond my control. Some of the best writing advice I’ve ever received is that you have to take care of your characters, because if you don’t, who will? I have to put them into the world with enough subtlety and depth that they aren’t doomed from the beginning.

Some of the best writing advice I’ve ever received is that you have to take care of your characters, because if you don’t, who will?

BS: You’ve seen success as a short story writer and as a novelist. Do you prefer writing in one form over the other?

KW: I like them both. They make me happy in different ways. But stories are probably a more natural extension of my brain. For me, stories are a kind of incantation. There’s this magic, like I’m trying to tell the story with the aid of only one deep breath. I also feel like, in the formation of a narrative, I can hold a single story inside of my head for a long time, this secret, and I can tell it to myself over and over and over, holding it all together, before I ever get it down on paper.

BS: Your work can be dark, certainly. However, you also use humor rather frequently — and to great success. How important is humor to you as a writer?

KW: It’s everything to me. It’s my way into the story a lot of times. I’ve said this before, and I’m not tired of saying it, but the line between sadness and humor is really permeable, and so I use that in my work. It’s hard for me to be serious, and so I use humor in the initial moments of a story, to disarm the reader, to show them this lightness in the work. And my hope is that the humor, as it touches up against sadness, starts to dim until you suddenly realize how dark the space has become. When it works, it makes me so happy.