interviews

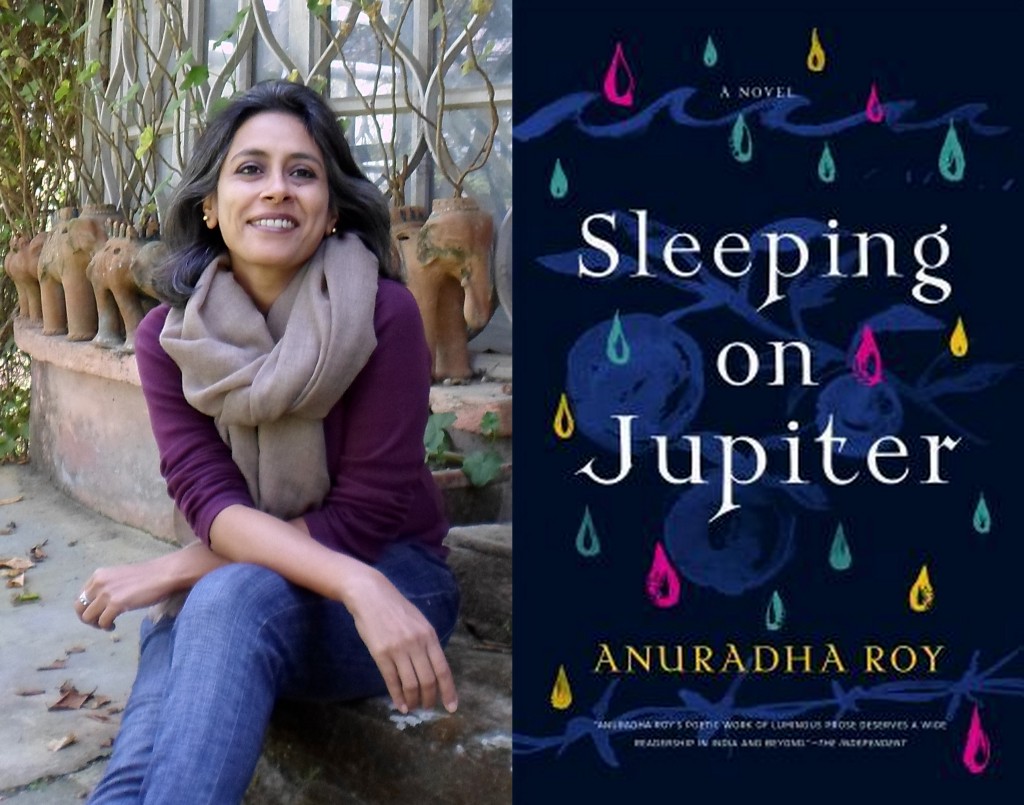

Anuradha Roy on Memory, Violence & Occupying Imagined Spaces

An interview with the author of Sleeping on Jupiter

Anuradha Roy writes the kind of immersive, atmospheric prose that you might not expect to be laced with fierce violence. But Sleeping on Jupiter, the latest novel from the Booker Prize-nominated author, doesn’t shy away from dichotomies, whether it’s a gruesome murder in a breathlessly beautiful setting or a religious guru who abuses children.

Sleeping on Jupiter (Graywolf, 2016) follows a group of people whose lives intersect as they visit Jarmuli, a seaside temple town in India. The core of the novel is a trio of women in their sixties, friends on a long-anticipated holiday, and Nomi, a punkish young documentary filmmaker who comes looking for clues to her childhood at a local ashram. With its wealth and squalor, religious fanaticism and feigned religion, tourism and claustrophobia, Roy’s fictional town of Jarmuli presents the dualities of modern India. As the trip unfolds, the characters navigate this unpredictable space which always threatens violence — especially towards women.

I had the pleasure of corresponding with Roy over email about her latest book, creating fictional landscapes, and the intentionality of writing.

Carrie Mullins: Sleeping on Jupiter is a beautifully atmospheric, almost cinematic, novel, whether it’s Nomi’s first home in the jungle, or the sea by Jarmuli, or the Scandinavian forest. The sights, sounds, smells, even the horticulture of a place seems to be important to the story. What drew you to these particular landscapes? How do you think about the function and place of environment in a novel?

Anuradha Roy: I remember the way books like Crime and Punishment affected me as a teenager. We used to get these cut price translations of Russian classics in India in those days and so tended to read Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky. The cold in them, the snow, the ice, the horses, the unfamiliar food, the long street names — a country I had never seen was alive in my head. Now when I think of the Shanghai of Tash Aw, the Wessex of Hardy, the rural landscapes of Bengal in Bibhutibhushan, the Scandinavia of Karin Fossum: the settings are inseparable from the characters and narrative. When I am reading a book, I like the feeling of being totally sucked into that world and place is crucial for that.

How particular and detailed and descriptive were those novels? I would have to go back to them to work that out, but the important thing for me is to try and evoke atmosphere and place with only a few details and to set the novel where I will want to live (in my imagination) for the three or four years it will take me to write the book. Even if a novel were to take place in one single room, I’d need to get the room vivid and right in my mind if I am to be able to write. It is not that you put in every detail you note down, but you need to know them for yourself.

CM: Along those lines, the novel is primarily set among the temples of Jarmuli. What inspired you to create this fictional town and why did you want to use a religious setting?

AR: Jarmuli is a temple town by the sea. Temple towns are quite unique in India — these are places for pilgrimage where practically the whole economic and cultural life of the town revolves around ancient temples. The book is set in a temple town partly because one of the themes of the novel is the place of religion in people’s lives — religion impacts different characters very differently in the book. Temple towns are also places for tourism and pilgrimage and therefore for transient relationships — there are quite a few of those in the novel.

The town is fictional because I like making up places as much as people. It gives me the freedom to create a world in which I can see my characters very clearly. The fictional places of my books grow partly out of real places I know, but I like to make and shape them for myself.

CM: Memory is a big theme in the book. Nomi has a fractured memory, Gouri is losing hers, and other characters, like Latika, have memories that they wish to forget. It’s interesting to write characters with incomplete memories because you, as the author, know more than they do. How do you think about the interplay between memory and character, and as an author, what to give and what to hold back? I was also struck by how the characters’ fractured memories related to each other, as if they each had part of the larger picture, the larger narrative of India.

AR: That’s very observant of you. Fiction has a great deal to do with memory — the writer’s own, those of her characters’ — it is impossible to escape. And this book is so much about attempting to excavate a past. During the time I was working on the book, I read how Oliver Sacks had described experiencing the London Blitz in one of his memoirs; however, his older brother told him they had both been away from London in boarding school at that time, that even though Oliver Sacks was certain he had gone through the bombing, he had in fact never experienced it, only read about it in letters from home. I found that fascinating — the fragility and unreliability, and yet the strength of memories.

So much comes from instinct and how good is the coffee you are drinking.

What to give, what to hold back — that is hard to pinpoint. I find the mechanics/the actual nuts and bolts of the writing quite hard to pin down. So much comes from instinct and how good is the coffee you are drinking.

CM: Violence shadows the characters throughout the novel, sometimes hanging back as a threat but often becoming more overt, especially against children and women. To what extent does this reflect the situation in India and to what extent is it just the world of the novel?

AR: The level of daily, routine violence in India is horrifying and disturbing. It is not just the world of the novel at all, it reflects our real lives here.

I didn’t start the novel intending to write about violence, but as Nomi grew in my mind, I began to feel more and more certain that her past was inescapably violent and that she and the other characters had to make their way in a pitiless environment.

CM: It is a pretty pitiless environment. Though for me there was a kind of strength, or maybe solace, in it being an ensemble novel as opposed to just Nomi’s story — and I think her story could sustain its own book. Can you talk a little bit about your decision to write Sleeping on Jupiter from a varied cast of characters versus focusing on Nomi?

AR: Actually, I’ve never written a book with a single storyline and a focus on one character. My books always seem to have largish populations, peoples connected with each other.

In this book, each character’s story illuminates the novel’s themes and concerns in different ways — sexuality, religion, violence, each of them has responses or experiences that set off the others’ experiences — or at least I hope so. And that their collisions and brushes with each other enrich the central narrative and also texture the narrative so that it is not one person’s saga but about love, fun, survival as well. I think the four women in the book particularly are very spirited, and even Nomi squeezes every last drop of juice she can from life, despite her environment.

(The problem with expressing intentionality or decisions is that it makes the whole writing process seem much more schematic than it is. When I am trying to make a living, breathing, absorbing, interesting entity out of some ideas and images in my head, I feel as if a lot of it operates out of instinct, out of ideas that come after a long walk, or waking from sleep thinking, that is what I need to do now, and running to a notebook to pin the thought down before I lose it. Of course writing decisions are absolutely logical and thought through, not once but a hundred times, but how that logic translates into the writing — when discussing it, the whole thing appears far more rational, crafted, and deliberate than it felt when writing it.)