Books & Culture

Art Must Engage With Black Vitality, Not Just Black Pain

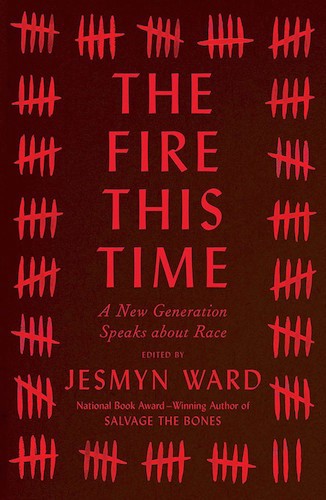

Books like "The Fire This Time" give depth and nuance to a reflection of Blackness in America

The wait in line for the Emmett Till memorial was about 45 minutes. I stood with the crowd in the National Museum of African American History and Culture as we shuffled forward slowly, like a real funeral procession. As I approached the doorway of the memorial, a guard gestured at a sign bearing Emmett’s name and, below that, one that read visitors weren’t allowed to take photos. The memorial, she explained, was set up like Emmett’s funeral in 1955, constructed to emulate the experience of those who had stood on line for hours to bear witness and pay respect. Through the memorial doorway were pictures of the funeral painted on the walls above Emmett’s coffin, organ music and gospel pumped through speakers, a surround sound of mourning.

Emmett’s actual coffin was present, mended and buffed to look as pristine as it had the day he was laid to rest. A photo of his battered face lay within, purposely set deep inside so that it was not in view from where we stood. Over 60 years ago Mamie Till Mobley had placed photos of her living, smiling, breathing son to the top of the open casket door. At the time, his beaten body rested behind glass as a before-and-after comparison. Outside the room, however, was a small photo of Emmett’s unrecognizable face, the same picture that appeared in Jet and brought a world, as well as Mamie, to its knees. As the guard had explained prior to entry, the setup was meant to serve as a moment of introspection and education. This display was constructed to understand the pain, reflect, and be immersed in a time in history those like myself were unable to witness.

To this day there’s no lack of evidence of Black pain. I’ve done a Google search for “lynching,” and let me say that you’ll not only see current listings of nooses hung as warning and threats, but the act as entertainment, as family time. Black pain as we have seen it in record, how it’s been described as fiction based off of history, includes the defilement of a human being, not only adults, not only children, but also the unborn ripped from mothers’ stomachs. This imagery can be numbing in its severity and proliferation. The record itself is necessary, and sadly isn’t even close to complete in reflecting the issues we see to this very day.

Now, when I say “Black pain,” I mean the transgressions that afflict Black people based on our ethnicity. I mean the violence and reaction to said violence that’s been part of the narrative for Black people in media. These narratives have been absorbed in stories that one cannot always turn away from. You know the car accident comparison? It’s applicable here in ways too. While the violence isn’t new, the medium has evolved. It’s available on a loop, on screens of varying sizes, in texts of all kinds. It’s neither accurate nor considerate to call the interest in Black pain a “trend.” Yet there appears to be a fixation with comprehending, or perhaps dissecting, what Black pain entails, particularly in texts. The yearning to understand can border on exploitation, resulting in that dissection becoming a primary narrative but also the most brutal to gain attention. In this respect I ask: When the bodies are available, scarred and brutalized beyond measure, are we seeing the deeper pain beneath? Or are we mainly reacting to the horror in disbelief, or to the relief that, supposedly, the worst has passed?

While the violence isn’t new, the medium has evolved. It’s available on a loop, on screens of varying sizes, in texts of all kinds.

Black bodies are piling up, in life and literature. I see the influx of the slave narrative regurgitate America’s history in various ways by artists, both of the Diaspora and not. The “reinvention” of Black pain aims to show the life we have while at the same time denouncing the violence we experience, yet the portrayals don’t always tap into the versatility of the Black community, nor do they examine the systems in place that created the disparity. For example, Underground Airlines, written by a non-Black author, was praised for taking a “risk” in exploring the slave narrative in a “new” way. The author was admired for focusing on the pain and motivations of a former escaped slave, but not for examining or critiquing the establishment that created this world via a privileged White gaze.

This is why the publishing industry may be quick to label books “Black Lives Matter” for marketing purposes as “an easier sell,” rather than acknowledge that the Black Lives Matter movement and the terrorizing of Black bodies are not one in the same. When the Black pain narrative is used to try to bring awareness but doesn’t examine the systems in place, these stories cater to the idea that Black people need to be saved, not that our political structures need to be questioned and altered.

As someone of African descent burgeoning on my own self-awareness, I ask of myself as editor and creator: To what extent am I adding to our pain and our humanity? When I write an abused Black woman or an incarcerated Black teen, am I introducing them with solely pain on the page or am I giving the character an existence someone else can see themselves in? I consider this as a woman of color, as an editor of color, and also upon seeing reactions to these stories. And I wonder, does the reader see me in these characters or do they see a narrative that makes them comfortable in the assumption of our helplessness? For the non-Black author it may be a challenge to imagine and illustrate this pain, but it also seems a preferred method to examining their privilege. It looks, to them, like a way to engage with hurt that seems easy to tap into, because it’s presumed that’s all there is to our existence.

In the essay anthology The Fire This Time, editor Jesmyn Ward says “I needed words.” Words are what I grasp for when considering our narratives and also inspiration for the words that have given us life and perspective. To fulfill my need I reached for Citizen; The New Jim Crow; Women, Race, and Class; Zami; The Sisters Are Alright; Dust Tracks on a Road; The Warmth of Other Suns; Brown Girl Dreaming; and The Souls of Black Folk, just to name a few in the nonfiction realm. And I repeatedly reached for The Fire This Time because I wanted to understand more than react. I wanted to comprehend the pain filling my own body and how it had been spilt on the page.

Ward’s anthology picks up where James Baldwin left off with The Fire Next Time. The tome was released last summer during one of the tensest and most absurd presidential elections of this century, which in a way means it published at the right time. What I found in those pages from the 17 contributors, including editor Jesmyn Ward, echoed life stages and legacy, parenthood and pain, coming-of-age stories and comeuppance, humor and history. These essays provided a deeper connection because Black pain was part of the story; Black identity, self-recognition, our own awareness brokered every page. Black pain was not the sole criterion for the anthology’s existence.

At a dinner — prior to the announcement that the policeman who shot twelve year-old Tamir Elijah Rice would not be charged — a friend exclaimed that no one can truly know the fear of being a Black mother of a Black child, particularly a son. The clattering of silverware against plates punctuated her dismay as she slapped her palm against the table. “I’m scared right now,” she added, to silence from all of us present. The intensity in her eyes and the directness of the words alone were enough for everyone seated, parent and non-parent alike, to comprehend that this fear is rooted so deep it never goes away. These are the fears of women like my friend, of Mamie Till Mobley, of Claudia Rankine.

The starkness and sparsity of Rankine’s “The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning” in The Fire This Time echoed the apprehension of my friend, a Black mother, at dinner: “At any moment she might lose her reason for living.” That sentence echoes the pain of Lezley McSpadden whose teenage son was described as a “demon” by the man who shot him and as “no angel” in a major publication. I could only imagine the kind of rhetoric Mamie felt at the hearing and later ruling from the trial of her son’s murderers. That, to a segment, this child was deemed “deserving.”

“Like Rachel Dolezal,” Kevin Young writes in his contribution “Blacker Than Thou,” “I too became black around the age of five. I first became a ni**er at nine, so I had me a good run.” Harriet Jacobs wrote similarly in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl that she didn’t come to know she was property until she turned seven years old. My own awakening means I first became a “ni**er” at eighteen, so by Young’s calculations I guess my run was longer than most. “Ni**er” was thrust at me through plexiglass at a movie theater I worked in, marked with the disavowal of my humanity by a woman older than me with a child by her side. From then on I couldn’t not see myself as one because I knew that others possibly did. That descriptor held in the air, making me wonder if my persona was immediately and irrevocably tied to a slur.

We need to better understand that the Black body is not simply a conduit that receives violence but also one that exudes beauty and complexity.

From Ward to Clint Smith to Mitch Jackson to Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah to Edwidge Danticat the essays and poems in The Fire This Time dissect the emotional toll of Blackness in America, but also the dynamics that make our lives visceral and not tragic by standard. In the call for more representative narratives, are we seeing a diversity of voices and explorations of our lives? Are we contributing to the bounty, and am I seeing myself in the stories present? Or are we reflecting on the issues, but not the reasoning behind them nor the ways to move forward? Not every book can or should be a map to “fix” society, yet we need to better understand that the Black body is not simply a conduit that receives violence but also one that exudes beauty and complexity.

When I ask myself about my aims as an artist, I go back to Emmett’s memorial and reflect on its construction, the intent behind the erected symbol in a national monument. A moment in history recreated with purpose to invoke emotion. Not necessarily the automatic outcry that can flood the streets, but that which makes us as individuals, and me as an artist, consider this nation’s history and it’s potential. By withholding Emmett’s battered face the memorial showed us the beauty of him in the before, the person he was prior to mutilation. Those of us on the outside can reflect on the teenager that could have been yet wasn’t allowed to be. I didn’t react to the horror alone, but to the reality that this was a child — a child in the same way of those who came after him such as Clifford Glover in 1973 and Trayvon Martin in 2012. I thought about the gravity of not seeing Emmett’s face, but instead experiencing the visceral feeling of the presentation — all the way to the video at the end, where we heard Mamie and Emmett’s cousin, now deceased, speak on that moment in time. I settled into what was presented to me and dissected how, in my own work, I could present this in a way that was also palpable.

In this frame of mind, thinking about “needing words,” I sat with each essay in The Fire This Time. Essays that furthered and inspired the conversation as Emmett’s reconstructed memorial did. I sat with Black pain, our pain, that is not to be refuted or ignored, erased or dictated.