Books & Culture

Baba Yaga Is a Lesbian

I found my queer freedom in the mythical witch’s complicated desire

In some stories about her, the path in the woods splits like a lip. It’s easy to picture if you try—there are birch trees standing close as teeth, dirt packed and hard. The fork in the road flicks quick like a snake’s tongue, with just as much bite to it. Picture it and know that no matter which road is taken, high or low, a witch waits at the end in a house standing on chicken legs, a fence dotted with human skulls surrounding it. Hold that house in your mind. See it loom.

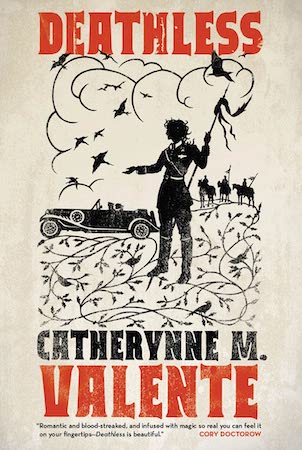

In March of 2014, I read Catherynne M. Valente’s novel Deathless for the first time. I was seventeen and closeted, living in the south, loyal only to fantasy novels and house plants. Women, as familiar to me as the body I saw in the mirror, were the epitome of terror. Every crush I had was a reinvention of the world in which the rules for adoration could not be taught. Instead, they were moments of fearful discovery, of hunger so huge it couldn’t be understood until after the inevitable crash. I kept the reality of my desire close to my chest and felt ashamed in its overwhelming totality.

Deathless introduced me to Baba Yaga, the wizened and cannibalistic witch of Slavic lore known to challenge the naïve protagonists who stumble across her hen hut with seemingly impossible riddles and tests. Maternal in some tales, menacing in others, she’s consistently an enigma—her actions are unpredictable and determined only by the nature of her fickle mood and desires. Throughout Valente’s novel, Baba Yaga is cruel and nasty to the protagonist Marya Morevna while simultaneously easing her into the reality of her choices; one moment threatening to swallow her whole, the next offering her the chance to abandon the idea of power in favor of a home, a mother, a bed and a book and a fire in the hearth.

In those years, I was starved for queer content in media. When I devoured Deathless in a single sitting and reached the line where Baba Yaga is revealed to be queer herself: “Do you have any idea how much I know about men? And women! Don’t look so shocked—after an eon or two of being a wife you’ll want one of your own, too.” I felt seen. I felt found out. I read the line over and over again, filled with sick and private pleasure—at that point in time I was considering that I might be bisexual, an idea that I’d later roll around in my mouth slick as a lozenge until I landed with the hard and sweet concept of lesbianism—and thought, of course. It was only natural that this terror of a woman wanted women to be hers, too. After all, hadn’t the thought of queerness always risen in me dark and fast as a wave, a compulsive violence that refused to be shoved to the corners of the mind?

It was only natural that this terror of a woman wanted women to be hers, too.

Baba Yaga became central to me—a private expression of my own wants and needs, this scapegoat for me to project my fears through. There seemed no safe word for what I was. It was simpler to see her, to want her, to feel her as close to me as a mother unashamed of my awfulness.

It wasn’t until a few years later that I found others drawn to the witch and her prevalence as a morally gray character in folklore, particularly in online spaces dedicated to art and writing. This demographic was overwhelmingly queer and embraced a previously unfamiliar presentation of violent and othered femininity. As a mythical figure, Baba Yaga was Other. She was not the wicked witch I recognized in fantastical readings, nor a wise goddess waiting with an outstretched hand. Her cruelty was demanded of her—her goodness was a reward. Adhering to no standards, she provided a new moral code where isolation was a choice she made to protect herself, and kindness was shown only to those who were deserving.

Baba Yaga’s ambiguity made her difficult to pin down and understand. How do you categorize an unknowable woman? When she came to me, I was locked away in the safe interior of my private world. I found that her selected isolation pushed her beyond the standards of typical “monsters” in lore. Now more than ever, there is an increasingly lesbian desire to be secluded on the outskirts of the world, one that Baba Yaga presented as safe and familiar. I spent years as a teenager dreaming that one day I might live with my best friend in the countryside where nothing was expected of us, our increasingly close and unwillingly toxic relationship pushing the boundaries of typical friendship.

When she came to me, I was locked away in the safe interior of my private world.

I found Baba Yaga most compelling in my closeted years because I felt that coming out would cause me to lose everything that I held dear, even when it seemed the only possible choice to keep me sane. My relationships dissolved in secret. I couldn’t seek comfort from anyone as my world imploded. I felt unknown, unseen, raw as a wound. Every crush and kiss felt like swinging an axe, wearing down the blade until the cut seemed too deep to reach. Both before and after coming out, it was instinctual to retreat and dig my heels into soft loam, answering those questions of self inwardly rather than splaying them open for public consumption.

But in myth, Baba Yaga embraced the crash. She was hungry and wanting but sought no one out. She waited at the edge of the forest and made a choice when the young girl showed up at her door, begging for help. The decision was clear; eat or assist. But the method was a sharper blade, a different animal. In her earliest tales she was a representation of Mother Nature, a being intertwined with death and rebirth as the deviated norm in Pagan ideology. Throughout the centuries her tale warped into a warning symbol for young girls—she was the future that awaited them if they chose the wrong path. In some stories, she devoured the girl whole. In others, she chased the girl across the countryside, creating rivers and mountains in her wake and bringing new life to the universe. And in one, she gifted the young Vasilisa the Beautiful a guiding light that burned up her wicked family and abusive home. In her assistance there was violence, and in her violence, there was ambiguous respect.

In Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir In the Dream House, Machado speaks of the queer villain in popular media, often reflected only in the margins as excommunicated representations of horror. When posed as an antagonist, Baba Yaga with her wild femininity is undeniably a representation of consequence in folklore. But I found her actions justified, seen in the clear correlation between her cruelty and her hunger, her hate and her desire. Regarding villains like Baba Yaga, Machado writes in her memoir, “They live in a world that hates them. They’ve adapted; they’ve learned to conceal themselves. They’ve survived.”

When posed as an antagonist, Baba Yaga with her wild femininity is undeniably a representation of consequence in folklore.

Baba Yaga’s representation in media has canonically queer roots, ancient and tangled. But there is no celebration in traditional stories. The warning to susceptible women is clear—Baba Yaga gives into her desire, then stands scorned and reviled along darkening tree lines. Yet she’s completely unburdened by a heteronormative world—she seeks only pleasure, only power, only the electric connection between her and another woman, and retreats to revel in her own wants. But as this othered villain, the starved witch is denied her redemption and humanity, and in turn I felt separated from my own.

After coming out, I expected to feel freed—instead, I was more lost than I had been when my sexuality belonged to me alone. In the scrambling rockslide of my identity, I sought a semblance of power. Baba Yaga’s lack of attention to public perception and moral repercussions provided me with a beacon. So much of my desire left me feeling monstrous. Who was I, if not a woman with a womb awaiting a cherry-picked path? My future felt narrow enough to fit through the eye of a needle. It seemed that any choice other than the life predetermined for me was one that would leave me despised, alone, and vulnerable to those around me.

But Baba Yaga is not hated. She is ancient, chaotic, untethered. In establishing that unpredictability, she regains power, cementing herself as a godless creature who owes nothing to the world that reviled her. I felt reflected in the concept that I could exist as something beyond the traditional. Baba Yaga did not demand goodness of me—only the answer most right in the world that I had carved for myself. And my rightness could be subjective and mine, no longer needing to adhere to the presented set of rules.

Baba Yaga did not demand goodness of me—only the answer most right in the world that I had carved for myself.

Through art, I pulled the repeated symbolism attached to Baba Yaga into my work. Her anthropomorphic house standing high on its chicken legs became a character itself as I painted it over and over, a space closed off from all traditional interiors. A skull on a stick took the place of a lamp. Dark water, thin birch trees, and mountainsides as sinuous as a woman lying on her side were common settings for the silhouetted girl I placed among them.

The dark shadowed shape of my character darted through Baba Yaga’s mythological land. That shadow self could perform the strange actions I never felt capable of. She could walk for miles into the wood. She could aim an arrow at a bird in the sky. She could sink into dark water, known only by reeds and snakes. She had choices, and these choices had no consequences—there was no good or evil, only one option or the other without repercussions waiting on the other side.

At times this creation felt like the only true expression of my queerness, despite being lucky enough to be verbally accepted by the people around me. I didn’t feel that I could be open with my family, for fear of being perceived as something twisted and wrong. Though I had supportive queer friends I didn’t entirely understand myself enough to feel seen by them. There was a barrier between my internal and external language—no matter how hard I tried to voice my feelings, the words didn’t fit, never conveyed the truth of me. Through the paintings I could piece together fragments of my own history. I could create a codex of symbols that represented the metaphoric language of my own folklore, with Baba Yaga guiding me along the way and forcing me to make choices that I felt might separate me from the truth of my own body.

It was so easy to look to Baba Yaga and dream of her—wicked with her speech, feeding her desire when the whim presented itself, protagonist and antagonist all in the same moment. In a genre where a moral lesson is typically the point of telling a tale in the first place, she denied logic and thrived as a paradoxical leader. She existed as an example that even if I told the truth and annihilated myself in the process, there would always be power in the choice.

In a genre where a moral lesson is typically the point of telling a tale in the first place, she denied logic and thrived as a paradoxical leader.

In the final pages of Valente’s Deathless, Baba Yaga states that she liked to help a woman most “when her perversity has made me proud.” I spent so much of my life feeling perverse—my wants, my fears, my needs all seeming like foreign thoughts meant for another mind that ended up trapped within my own. But that statement alone was permission for wildness, deviation clicking into place like an igniting gas range where I stepped out of one life and into the next. I could be who I had always been, or I could notch the arrow in a waiting bow and prepare to watch it fly.

Before leaving the older and harder Marya Morevna behind to choose her fate, Baba Yaga asks, “How did she turn out, the woman you might have been?”

By forgiving my desire, I let the woman I might have been walk past me. Her world would be her own. I unfurled the tethered part of me that always felt most terrifying and fell in love with my own lesbianism. It was a beautiful thing when finally considered, sharp enough to hurt when I stared directly at it. I turned my eyes to it and did not look away.

It seems sensible to take the hate of a world and let it turn you into a hag, pull your darkness inward until it is a hard and heavy coal in your throat. But to sharpen it is the challenge. To desire is the challenge. To watch what you want walk through the door and snatch it up is the test of all tests, the mettle in the moment, the deciding factor that declares otherness and turns it into choice. The path splits in the woods. There is no delineation—each dirt road seems to glitter with promise, to grow deeper with a threat. The power is in walking, one step after another, exposed in the dark just waiting to be seen. Through Baba Yaga, we see the beauty in unabashed identity. She wants and she eats and she becomes more ancient than death.

I saw her, and I wanted. I hadn’t permitted myself hunger in so long.