essays

“Barracoon” Went Unpublished for 87 Years Because Zora Neale Hurston Wouldn’t Compromise

Hurston cared about authenticity more than fame — and finally, the world is catching up to her

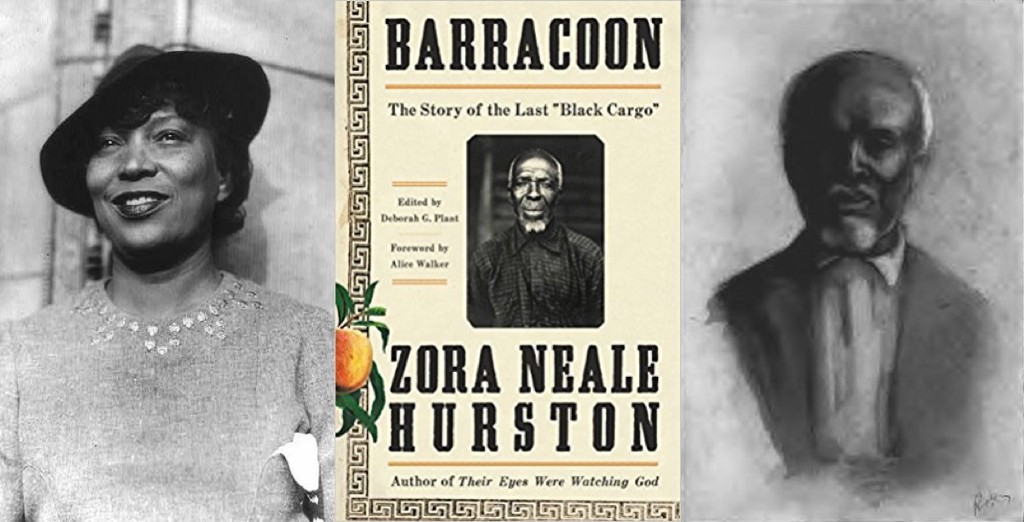

In Daytona Beach during the spring of 1943, Zora Neale Hurston penned a characteristically candid letter to the poet Countee Cullen. Both would later become known as quintessential voices of the Harlem Renaissance, but Hurston’s letter to Cullen did not center around their literary success. Instead, it was about their mutual defiance of literary trends and their shared resistance to doing what was expected, approved, or popular.

“You have written from within rather than to catch the eye of those who were making the loudest noise for the moment,” Hurston wrote. “I know that hitch-hiking on bandwagons has become the rage among Negro artists for the last ten years at least, but I have never thumbed a ride and can feel no admiration for those who travel that way.” As the letter continues, Hurston addresses the danger of palatability and the power of its opposite. “Some of the stuff that has passed for courage among Negro “leaders” is nauseating. They are right there with the stock phrases, which the white people are used to and expect, and pay no attention to anymore. They are rather disappointed if you do not use them. But if you suggest something real, just watch them back off from it.”

By this time, Hurston knew that her nonfiction work Barracoon, consisting of hours of interviews with Cudjo Lewis, one of the last survivors of the slave trade, would not be published as written. The publishing world insisted that she tone down her subject’s dialect, making the work an easier read for white audiences — and less authentic. But as much as she wanted Lewis’s story, and her book, brought to life, Hurston’s ethos as a writer wasn’t rooted in pleasing the masses, but in offering a true depiction of what it meant to a Black, to be American, and to be human. She would rather see her work rejected than watered down.

The friendship between Hurston and Cullen — as depicted through Hurston’s letter — stems from their shared inability to give way to the status quo. Often interpreted as brazen rebellion, their dedication to storytelling and to the stories of their people is what ultimately made their work legendary. Their words became transcendent and timeless because of their conscious resistance to conformity. Even then, Hurston knew the stakes were high. She, like Cullen, was aware of the risk of taming ones tongue for the sake of audience. And so, despite the consequences, she ignored the expectations of her time. She dug deeper for something truer, and by doing so captured the marrow of who we are as a nation and a people.

Principled and perhaps a little defiant, Hurston was zealous when it came to telling it like it is. The work she left behind proves that Hurston’s confession to Cullen is true: “I have the nerve to walk my own way, however hard, in my search for reality, rather than climb upon the rattling wagon of wishful illusions.” Her rejection of convention and refusal to embrace illusion resulted in touchstone texts like Their Eyes Were Watching God, Go Tell My Horse, Dust Tracks on a Road, and at last Barracoon. Nearly a century after the publication of her first book, the world seems ready to hear the story that Hurston refused to sanitize.

She dug deeper for something truer, and by doing so captured the marrow of who we are as a nation and a people.

Completed in 1931, Barracoon recounts the life of Lewis, also known as Oluale Kossola: the last living African slave to be shipped into the United States as cargo. The book’s manuscript, like its author and the story of its subject, was nearly lost to time due to Hurston’s refusal to tailor Barracoon’s prose to the liking of her white editors, who requested for her to use “language rather than dialect.” Yet, if she had complied with their wishes, the story that she had intended to tell, the story of Lewis, would have been erased. His experiences, as he recounted them to Hurston, would have been muffled by the demands of her publishers. The authenticity of the narrative would have perished. Hurston knew that, and so she chose to preserve her reality rather than the illusion. Consequently, Hurston’s manuscript remained unpublished for 87 years.

Countless writers — then and now — have grappled with what they’re willing to sacrifice in order to become a published author. Whatever the genre, we ask consciously or subconsciously ask ourselves these questions: Do I want to be known? Do I want to be famous? Am I willing to become a commodity? Can authenticity be synonymous with success?

How much of the truth are we willing to sacrifice before it’s no longer the truth? For Hurston, the answer was clear. Compromising her vision wasn’t an option, even if it meant that her manuscript and Cudjo Lewis’s story would never see the light of day. Although fellow luminaries like Richard Wright criticized Hurston’s work as having “no theme, no message, no thought,” her decision to keep the dialect of Barracoon unadulterated suggests that Wright’s admonishments were merely the byproduct of misogyny and the shortsightedness of respectability rather than a valid critique. Amidst the chaos of financial instability, racism, sexism, and the pressure to produce as much work as possible, Hurston was constantly aware of the industry’s interior. “Publishing houses and theatrical promoters are in a business to make money,” she wrote in her essay “What White Publishers Won’t Print” for the 1950 April edition of Negro Digest. “They will sponsor anything that they believe will sell… publishers and producers take the stand that they are not in business to educate, but to make money. Sympathetic as they might be, they cannot afford to be crusaders.” Hurston knew that her editors’ request was as much about her race as it was about profit. Their demands were strategic, but also systemic, revealing that although the work was valid and the story was necessary, that alone was not enough. The book that would become a highly anticipated title in 2018 was not viewed as marketable enough to publish without whitewashing it during the 1930s.

Compromising her vision wasn’t an option, even if it meant that her manuscript and Cudjo Lewis’s story would never see the light of day.

Like the man whose life is depicted throughout the pages of Barracoon, Hurston yearned to be heard on her own terms. In the first chapter of Barracoon, Hurston tells Lewis, “I want to ask you many things. I want to know who you are and how you came to be a slave; and to what part of Africa do you belong, and how you fared as a slave, and how you have managed as a free man.” In response, Lewis replies, “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want telle somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name… I want you everywhere you go to tell everybody whut Cudjo say and how come I in Americky soil since de 1859 and never see my people no mo’.” Hurston’s adherence to Lewis’ wishes and her dedication to her vision for the book never wavered. Just as Lewis requested, Hurston documented his story as he told it. The world just wasn’t ready to hear it, but now his life is known. Hurston’s book exists, uncompromised.

As a folklorist, anthropologist, novelist, essayist, and playwright, Hurston’s ethos was rooted in the preservation and accurate depiction of her culture. Her refusal to do anything less undoubtedly impacted her career — and yet her legacy persists. Hurston’s steadfast dedication to her truth proves that she was in many ways right, even if she suffered for being so. The lens she applied to the world and the written page never wavered, even when the world asked for something that was easier to consume. Hurston was aware of the power of authenticity, the power of her refusal to compromise. “I not only want to present the material with all the life and color of my people, I want to leave no loopholes for the scientific crowd to rend and tear us,” Hurston wrote in a 1929 letter to Langston Hughes. “I know it is going to read different, but that is the glory of the thing, don’t you think?” Whether it be Barracoon, fieldnotes, a short story, a letter to a friend, or a play, Hurston’s work is permeated with the unfiltered “life and color” of her people. That was her concern, not palatability or fame.

Barracoon’s publication is pivotal for many reasons. It comes at a time of political upset, racial tension, and our nation’s reckoning with the ghosts of its past. Lewis’ life, much like Hurston’s, is a testament to the necessity of telling your story unapologetically. The pages that Hurston wrote prove that even if the world is reluctant to listen, eventually your voice will be heard and your words will urge others to open their mouths and speak. Barracoon urges us to examine what we yearn to gain from a story and ask whether we are willing to really hear what it has to say. Anyone who reads this book will walk away from its pages wondering how many stories as necessary as Barracoon will remain unpublished until we as readers are ready to reckon with unfiltered narratives. It will make you question whose voices you are willing to hear.