Books & Culture

Before the Internet, TV Guide was the Place for Smart Criticism

Remembering the days when John Cheever, Joyce Carol Oates, and John Updike wrote for a forgotten cultural touchstone

My family was a TV Guide family. Every Thursday the issue would arrive, flexible and thick, giving promising weight to that day’s batch of mail. On the table next to my father’s recliner was a marked-off spot where the TV Guide was to be stashed when nobody was using it. This rule of order was a rare critical point of agreement in our house. It was a stop-the-presses moment whenever the TV Guide went missing, on the same level as having to scour the neighborhood whenever the dog wandered off.

I watched a lot of television as a kid in the eighties, and my family couldn’t afford cable until my junior year of high school, so the machinery of pre-digital TV broadcasting was an object of fascination for me, much the way that some commuters follow upgrades to public transit. I memorized call letters, channel numbers, and network affiliates; I knew which affiliates belonged to the same network because their program listings were bulleted together in the TV Guide.

It was a stop-the-presses moment whenever the TV Guide went missing, on the same level as having to scour the neighborhood whenever the dog wandered off.

Nowadays, nobody even identifies channels with their numbers anymore, except when they’re painted on the sides of news vans. But in the days before remote control I could spin the dial through the void of snowy frequencies — extending to the faraway UHF tundra of Channel 83 — to stop on a dime on any channel I wanted.

We lived north of Boston, a TV hub that had four low-number network stations and three decent independent stations. Since our house had a rotating aerial antenna, we could also watch, with tolerable levels of snowiness, affiliates in New Hampshire, Worcester, Rhode Island, and even Maine when the weather cooperated. The compactness of New England geography meant that all of these channels got listed in our TV Guide. More than any young adult novel, it was my weekly mandatory reading.

Why People Don’t Like “I Love Dick” (Hint: Because It’s About Women)

On one level, TV Guide was a template for planning your TV-watching week. The front matter was crammed with articles, reviews, and interviews that teased new episodes of shows. If a new episode of MacGyver ran up against a Very Special Episode of The Hogan Family, you knew you would have to make a decision. You could read the brief present-tense episode summary (“MacGyver joins a U.S.-Soviet team trying to salvage gold from a wrecked World War II transport plane”) and work out a schedule — not a small thing if your family owned only one TV.

If a new episode of MacGyver ran up against a Very Special Episode of The Hogan Family, you knew you would have to make a decision.

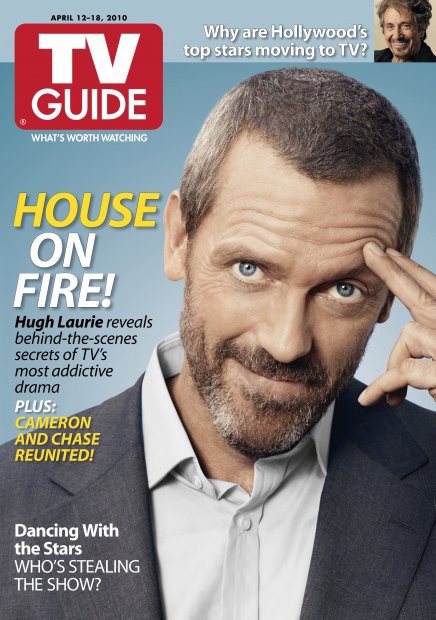

It’s a dated notion now — evaporated, of course, with the advent of TiVo, On Demand, and Internet TV, all of which encourage at-will binge-watching on our laptops in bed. (Even the red TV Guide cover logo evolved with the shape of television screens — rounder in the Philco years, corners squared off in the 1970s, and, in its 21st-century incarnation, stretched horizontally to match the aspect ratio of flatscreens.)

But in its best years, TV Guide was more than a guide; it allowed you to participate in the cultural conversation of television even through those shows you never watched, like you might read The New York Times Book Review about books you don’t ever plan to read. Before the Internet was available to host this conversation, TV Guide was the document that brought it to the masses, physically and metaphorically denser than the gossipy, photo-filled space-holder we find in the supermarket today. Its editors were determined to ensure that Americans embrace television as serious, even highbrow art. Toward that end, the magazine brought in the heavy lumber, a who’s who of literati, to write for its pages. It brought in John Cheever, a National Book Critics Circle, National Book Award, and Pulitzer Prize winning author, to write about the experience of watching TV commercials:

I am not an aesthetician, but in my opinion any art form or means of communication enjoys a continuous process of growth and change, rather like something organic, and one must be responsible to one’s beginnings.

Also delivering critical wit and social commentary for the magazine were Clive James, Anthony Burgess, Margaret Mead, John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, David Halberstam, and William F. Buckley, Jr. (“The Winter Olympics aren’t a velleity for the Swiss,” wrote Buckley in 1988. “They are a compulsion.”). For much of its early existence, right alongside The New York Review of Books, TV Guide treated television as a medium of cultural heft and assumed that its readers wanted it that way. Its vocabulary took for granted that its audience, when they weren’t tuning in, were reading books.

TV Guide was more than a guide; it allowed you to participate in the cultural conversation of television even through those shows you never watched, like you might read The New York Times Book Review about books you don’t ever plan to read.

And so into the living room it brought theory: “Why the Feminists Condemn Television” reads the cover of the August 8, 1970 issue, with Marlo Thomas of That Girl lying on the grass.

It tackled social concerns: “How TV Police Shows Give Police a Headache” (December 18, 1971, over a picture of the Partridge family).

It even attempted conscientious media criticism: over Michael J. Fox on the cover of the September 21, 1985 issue are headlines teasing a retrospective of the hostage crisis in Iran. “Were There Payoffs to Terrorists?” “How Fair Was the Reporting?” “Was TV a Good or Bad Influence?”

This was the forum against which the anthropologist Mead, in January 1973, profiled An American Family, the twelve-part PBS documentary series widely considered to be one of the earliest entries in the genre of reality television. Observing the members of southern California’s Loud family from the bushes, Mead identified the then-unnamed genre as “a new kind of art form … as significant as the invention of drama or the novel — a new way in which people can learn to look at life, by seeing the real life of others interpreted by the camera.”

In was in this cozy medium that Joyce Carol Oates, in 1985, wrote a simmering defense of Hill Street Blues, a show that shocked her for presenting something beyond what she expected of television, something “Dickensian in its superb character studies, its energy, its variety; above all, its audacity.”

In was in this cozy medium that Joyce Carol Oates, in 1985, wrote a simmering defense of Hill Street Blues, a show that shocked her for presenting something beyond what she expected of television.

Oates’ essay came more than twenty years after Susan Sontag defended the value of camp to high culture in Partisan Review and twenty years before dramas like Mad Men would be analyzed by television critics, such as The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, as avenues for the complex moral reasoning once offered almost exclusively by novels. Nussbaum was awarded the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in the category of Criticism precisely for her capability of leveraging the art as it reconciled its auteurist and commercial ambitions. “There’s something … that I find myself craving these days,” she wrote in response to the Mad Men finale in October 2015, “that rude resistance to being sold to, the insistence that there is, after all, such a thing as selling out.”

The boundaries once closely and politely hewn by television are gone: not just the tidy genres — the “Comedy” or “Western” or “Crime Drama” suffixed onto the entries TV Guide’s listings — nor the screen dimensions, but the size of the bite. Episodes aren’t episodic anymore. Not only can shows be watched in binges, they can be re-watched just as easily, so arcs are written with a forgiveness of the leaky human memory. It can take three series binges of Arrested Development before you realize that its visual gags (the dozens of hand references) in Season One set up a plot line (Buster Bluth losing his hand to a seal) late in Season Two. Where television used to be vegging material, now it’s presented in a way that expects the viewer to subscribe.

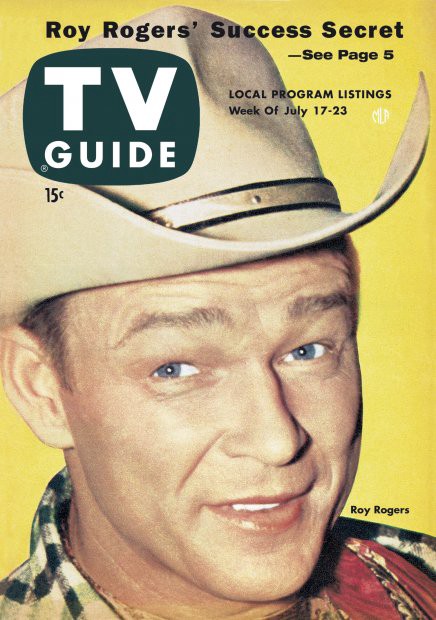

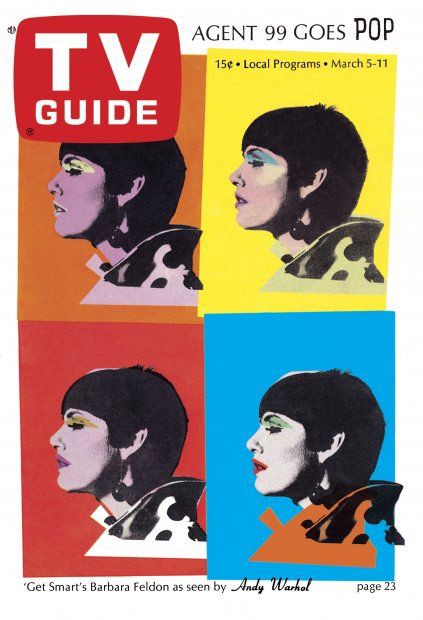

TV Guide’s writers cared about how media was received by the viewer, held hostage at home by four networks and a scatter of affiliates. This was a time, after all, when the literary and the visual often intersected: when Dick Cavett had to separate the feuding Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer, when Sontag and Marshall McLuhan were cameoing in Woody Allen films. TV Guide understood that, for many, television was the conduit through which history would be learned and events of the day critiqued. And its forays into the highbrow were not limited to the written word. For the cover of the March 5, 1966 issue, Andy Warhol featured Get Smart’s Agent 99, Barbara Feldon, in a Beatles-esque foursquare silkscreen. Salvador Dalí painted a moonscape-as-commentary for the June 8, 1968 issue that also featured an interview with the artist. Such was the occasional dispatch of culture that ended up in the hands of homemakers and teenagers and anyone who just wanted to know who Johnny Carson’s guests would be that week, or which Creature Feature movies were showing on Sunday afternoon.

Walter Annenberg was already descended from a publishing family when he launched TV Guide in 1952. (His father, Moses “Moe” Annenberg, published the Daily Racing Form and later purchased The Philadelphia Inquirer.) Annenberg’s TV Guide essentially took the formats of preexisting local TV-listings publications out of New York, Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington, and Scranton — all of which he purchased — and streamlined them into a national resource with regional tangents. The first national issue hit newsstands on April 3, 1953. The cover featured a blanket-wrapped Desi Arnaz, Jr., who had been born to Lucille Ball three months earlier via a Caesarian section that was scheduled to coincide with the birth of Lucy Ricardo’s son, Ricky, on I Love Lucy, on January 19, the eve of Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration. The tabloidish headline — “Lucy’s $50,000,000 Baby” — was the first wry grenade tossed in the magazine’s critique of celebrity endorsement, suggesting that corruption was at hand in the decision to bring into the world a child with no choice but to be famous.

With that, TV Guide seized the reins as the playbill that introduced television to its audience of new users. There were other television viewing guides, but the ubiquity of TV Guide was so accepted that some chair manufacturers would include pockets sized precisely to keep the digest-size magazine close at hand. In the 1980s I owned a TV Guide-branded board game, with TV trivia questions printed in booklets the same size as the magazine.

In 1988, Triangle Publications sold TV Guide to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. for $3 billion. It was under Murdoch that the magazine was thinned into more of a pop culture pamphlet, stripping away the challenge and commentary, outside of its “Cheers & Jeers” section. (The move suggests that Murdoch, for all his hard editorial influence on his other properties, felt that politics had its place, and it wasn’t in the home.) Ten years after the News Corp. acquisition, TV Guide was acquired by what would later become GemStar International Group, maker of VCR Plus recording devices, at which point the brand’s focus switched to digital menus, interactive programming, and producing Entertainment Tonight-style spotlights on the TV Guide Channel.

TV Guide, in its best incarnation, was doomed long before the developments of DVRs. As digital cable guides became more of a preferred utility, the magazine changed its format, abandoning the digest size in 2005 in favor of the larger-size format, doing away with local editions, then switching to a biweekly publishing schedule the following year. It still gets sold in the checkout aisle next to Us Weekly and Soap Opera Digest, and, if reports are to be believed, it still makes money.

TV Guide, in its best incarnation, was doomed long before the developments of DVRs.

I don’t watch anywhere near as much television as I used to. I TiVo Jeopardy! every evening. When I do binge-watch a show, it’s usually an older series such as The Rockford Files or thirtysomething, something I missed the first time around that taps into my nostalgia for older production models, storylines forged to maneuver around analog limits, or even just for cars with bumpers made out of metal.

Part of that can be attributed to snobbery, I’ll admit, but I think it also arises from a hesitance to subscribe to something new that I know will ask so much more of me than it used to. Even a great series like Sherlock, with its feature-film-length episodes and piling up of clever dramatic twists, can be an exhausting project to watch, requiring not just a blocking out of time but a strategic intake of breath before the journey begins.

It used to be that television was the medium through which powerful external forces subverted their way into your living room. But then television broke out of the living room, knowing that the consumer would follow it wherever it went. And maybe that’s why the model that once thrived for TV Guide can no longer work: it’s because we already know more about what we watch and how we watch than John Cheever or Joyce Carol Oates or any critical mind can tell us.