essays

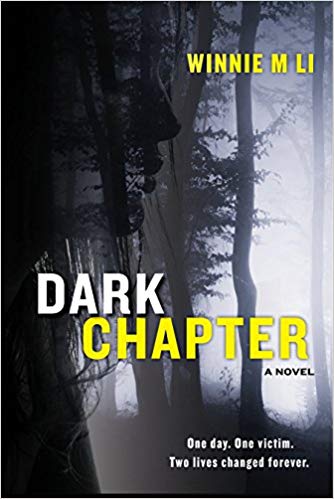

Being Published in Asia Changed Everything About My Asian American Writer Experience

My book tour made me think about how publishers—and readers—react differently to writers who look like them

Last spring, I was flown to Seoul to launch the Korean edition of my debut novel, Dark Chapter. My publisher Hangilsa Press had astutely monitored the growing public response to #MeToo in Korea and had decided to not only bring forward my novel’s publication date, but also set up a full promotional “tour” for me with multiple TV interviews, public talks, and a press conference. In some ways, it was every debut author’s dream: a round-trip flight halfway across the world, five nights in a luxury hotel, guest of honor treatment throughout. It was also completely exhausting, requiring nonstop eloquence and enthusiasm about a difficult topic (my own rape)—and all this while jet-lagged, surrounded by translators. (I am Taiwanese American, not Korean American, and I don’t speak any Asian language fluently, but my Korean publisher, media, and audiences were unfazed by the language gap.)

It was simultaneously exhilarating and lonely, yet also the kind of publicity platform any ambitious novelist would love to have. But throughout most of this, a question popped up, the inverse of a more familiar one: Would my Korean publishers have done this if I were white?

I imagine most people of color living in the West have internally teased a question like that at various points in their lives: Would I have been treated like that if I weren’t Black? Would those strangers have said that to me if I weren’t Asian? Would I have gotten the job if I fit more easily into the mainstream culture—i.e., if I were white? Writers of color are accustomed to this question, too, and indeed, I asked it of myself many times while trying to find a U.S. publisher for Dark Chapter. Would this be so difficult if I were white, I wondered, or if I conformed more stringently to the narratives that white readers expect of Asian stories?

Dark Chapter struggled to find a U.S. publisher. In 2015, when it was on submission, many publishers were disturbed by its portrayal of sexual violence, which some editors considered “too real” or “too unflinching.” (An ironic comment, given how much some genres rely on sexual violence as a trope.) But the exact opposite happened in Taiwan in Autumn 2017, after my novel won The Guardian’s Not The Booker Prize. There, a five-way auction for Complex Chinese rights led to my biggest advance thus far. The Taiwanese edition of my book has just been published in April 2019. Rights for a mainland Chinese edition sold for more than twice the Taiwanese advance. Why this difference between U.S. and Asian publishers’ reactions to the same book?

You could argue Dark Chapter still falls within a tradition of “pain narratives” expected of writers of color by Western readers. But my book doesn’t directly address issues of race, even though the heroine’s identity as Asian American informs her experience of the world. It is more a story of gender and class, following the well-educated heroine’s encounter with the feral, illiterate Irish teenager who rapes her in Belfast. If my book were more overtly Asian (instead of inhabiting the amalgamated, international background that I come from), would American and British publishers have known how to market it more easily as literary fiction? If writers like Lisa Ko, Chang-Rae Lee, and Amy Tan address the immigrant experience, are all writers with Asian last names expected to as well?

The total advances from my three Asian publishers exceed the total advances from my nine Western publishers.

It seems to be a very different experience for Asian American writers in Asia. While on my Korean book tour, I encountered a very unfamiliar notion of privilege: in addition to losing out on opportunities because I wasn’t white, I was also getting new opportunities precisely because I was Asian American. The total advances from my three Asian publishers exceed the total advances from my nine Western publishers. And like my Korean publishers, my mainland Chinese publishers are hoping to fly me to Beijing to promote the novel. I can’t help but notice that the only publishers to have invested in a promotional tour thus far are Asian.

The cynic in me focused on the “optics” of marketing authors, but when I got to Seoul, I realized there may be some deeper emotional truth in promoting an Asian American female author to other Asian women. Since my book deals so directly with the painful, often private trauma of rape, I believe it meant something to potential readers in Korea—specifically female readers—to see an author who looked like them. As if our shared experience of womanhood, gender inequality, and (for some) sexual assault, somehow felt closer to theirs, because we were the same race.

Nominated for an Edgar Award in 2018, Dark Chapter is a fictionalized retelling of my own real-life stranger rape, but imagined equally from the perspectives of both the victim (a character with strong parallels to myself) and the perpetrator (in real life, an Irish teenager who stalked me in a park). It is set largely in Northern Ireland (where my rape took place) and London (where I lived at the time, and still do do now), so there is no direct connection with contemporary Korean or Asian culture, save for the fact that the victim, Vivian, is Taiwanese American.

But even this representation of Asian womanhood seemed to be something Korean women readers identified with, particularly around a subject that carries such a cultural taboo. During my promotional tour, Korean women lined up at the signing table, some of them sharing their own stories of sexual trauma with me. Some would cry, telling me how grateful they were I had written this book. My literary translator, Byeol Song, is herself a rape survivor and public about this—and I, in turn, was grateful for the emotional authenticity she gave to the Korean edition. Elsewhere on my tour, I conversed with leading feminist scholar Dr. HyunYoung Kwon-Kim, participated in a special discussion with women journalists, gave a lecture for Women’s Studies Masters program, delivered a TED-style televised talk. At night in my hotel room, I cried on my own—partly out of sheer exhaustion, partly out of the chance to connect with these women living on the other side of the world, Korean readers I wouldn’t have otherwise met.

If I were white and talking about my rape, would Korean readers have thought my life experience was too different from theirs to relate to?

My professional life in London often involves enabling conversations among rape survivors. Predominantly, participants in these conversations are white, although there is certainly ethnic diversity. But my experience in Korea raised another question. Because sexual assault is so deeply personal, do people naturally feel drawn to someone whose experience seems closer to theirs—because of how they look? If I were white and talking about my rape, would Korean readers have thought my life experience was too different from theirs to relate to, despite also being a rape survivor?

Strangely, I, too, found myself being more honest about being an Asian American author in the West, when Korean audiences asked me about it. I said that writers who looked like me were often expected to write about “being Asian,” rather than a more “universal” experience like gender or sexual assault.

It was the first time I felt I could even mention that publicly when discussing the book. To a more general, Western audience, I worried that such thoughts might label me a whiney or ungracious minority writer. But in Korea, I sensed a duty to be honest about the kinds of unspoken discriminations that still happen to women of color in the West. Perhaps I myself perceived a sense of kinship with these Asian women. Perhaps the optics affect all of us—even the most cynical—into an imagined sympathy with those who look like us. And yes, visibility matters. Even a symbolic visibility enables an author to connect with an audience.

Even a symbolic visibility enables an author to connect with an audience.

I am glad my Korean publishers recognized the value of promoting an Asian American female author to Asian women readers, but our readerships shouldn’t be limited by race. It is truly a shame if Western publishers perceive a problematic gap between the race of an author and the race of a book’s intended readers—because there are readers of all ethnicities in the West, and we are all capable of empathy. And literature, after all, is meant to transcend such human particularities. As a Taiwanese American girl growing up in the U.S., I certainly identified with characters who didn’t come from a world anything like mine: Scout Finch, Holden Caulfield, Bigger Thomas. And indeed, it works the other way around. I’ve had white male readers say that reading Dark Chapter made them understand a bit better what it’s like to be a woman, who cried reading the scenes of the heroine’s experience of the criminal justice system. So if they can identify with a Taiwanese American heroine, then that’s already one step towards progress.

Looking ahead, I am curious to see how my Taiwanese and Chinese publishers will handle Dark Chapter. (Of the ten book covers finalized so far by international publishers, only the Dutch one explicitly shows an Asian face in the cover design). My mainland Chinese publisher will roll out the Simplified Chinese edition to billions of potential readers later this year. A British-Vietnamese producer is optioning the film rights. And, as I write my second novel, I also wonder if it’s a disadvantage with Western publishers that my work doesn’t address ethnic identity more explicitly. Should I write what’s easier to market by an Asian American author, or what truly interests me? Of course, it’s the latter. As I’ve been told time and time again by other writers, you just have to hope your work will find its readers. Regardless of your race and theirs.