interviews

“Besharam” is a Survival Guide for Shameless Brown Girls

Priya-Alika Elias wants to start a rebellion against the ideal of a "good" Indian woman

Shameless. This is a word every brown woman knows intimately. From my British home in Brighton to my Indian home in Goa, from Toronto to New York to Lahore, brown girls everywhere are constantly called “besharam.”

It doesn’t have the same ring in English, shamelessness shorn of its cultural specificity. Besharam is an accusation that cuts deep, in all directions. It means that you haven’t just brought shame upon yourself — through your choice in clothes, your too-loud laugh, your music taste — but also upon your family, your community, a sense of cultural honor. In 2011, when Delhi women organized a slut walk, they called it a besharmi morcha [protest]. They didn’t march as sluts, they marched as women without shame. The exact opposite of what a “good” brown woman is supposed to be.

Priya-Alika Elias isn’t having any of it.

Elias’s debut book is a brown girl’s survival guide disguised as a memoir. Besharam: Of Love And Other Bad Behaviours covers far-ranging topics spanning rape culture, heartbreak, “aunties,” eating disorders, and the impossible weight of a brown body in a sea of whiteness. Set between America and India, Besharam is equal parts hopeful and heartbreaking, and despite its tenderness, calls forth the kind of rage that makes you want to set the world on fire. And I hope it inspires brown girls the world over to do just that.

In the run up to Besharam’s publication, Priya and I met over the internet to talk about white boys, self-love, Twitter, Asian parenting, and why it’s important for brown girls to stand up for each other.

Richa Kaul Padte: Priya, let’s start with white boys! Like you, I became an adult in a white country, and young men trying to chat me up would often say, “But you don’t look Indian.” They meant it as a compliment, and the worst part is that over time, I began to take it as a compliment too. In Besharam you write: “How can I describe the specific wound left left…by white men who say, ‘You’re attractive, for an (X ethnicity)’?…We know what happens to a wound when it festers.” What do you think is the result of these festering wounds? Because damn, do they fester.

Priya-Alika Elias: For me, it meant that I tried to shed my Indianness. Since white boys didn’t think Indian girls were attractive or cool, okay fine, I would no longer be Indian! Obviously I couldn’t rid myself of my identity so easily, but I stopped wearing Indian clothes or accessories. I made a conscious effort to not have any Indian friends. I never talked about India or Indianness. I was absurdly pleased when people mistook me for any other ethnicity.

It took me a long time to understand that white boys were not the universal arbiter of attractiveness.

It took me a long time to understand that white boys were not the universal arbiter of attractiveness, or to see any desirability in myself. I imagine it’s just as difficult for many brown girls abroad. As women, we are already so aware of our looks — and what role they play. As brown women, white boys can be immensely damaging to our self-esteem, to the point that we wish to cast off our fundamental identity.

RKP: Please let’s talk about Rupi Kaur. Clearly so many white people (and men of all ethnicities) resent her success. Like you point out, she outsold motherfucking Homer. And I love that you tie this success to how she constantly preaches self-love to brown girls. You write, “What do we brown girls know about self love? Who is teaching us to love ourselves?” What is it, do you think, about a self-confident brown woman that poses such a threat to the world?

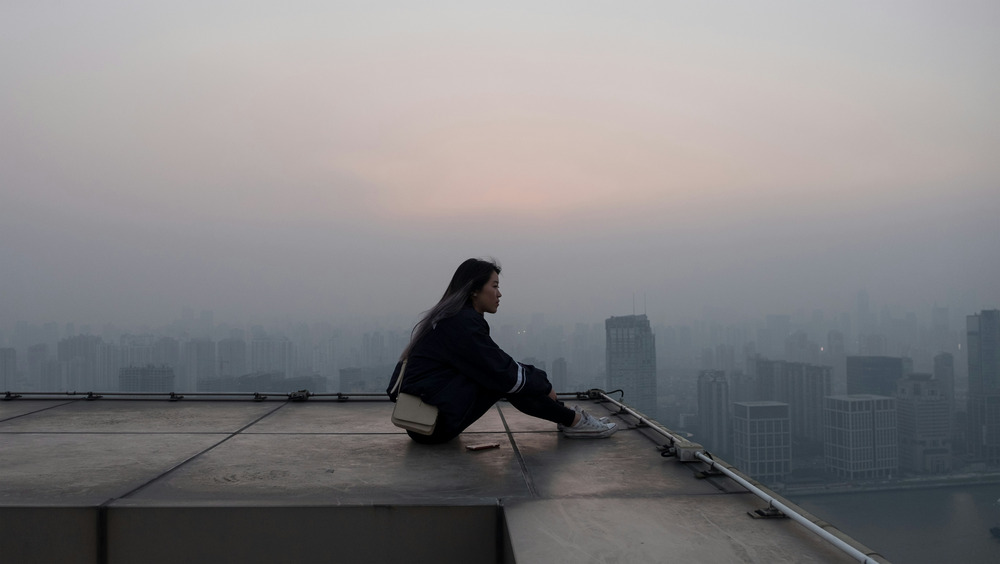

PAE: The ideal brown woman is meek, restrained, “good.” From birth we are taught how to behave around other people, aren’t we? Even how to sit. There is a compliment in my native language, Malayalam: adakkam odakkum. It means “a good woman sitting in the corner, occupying as little space as possible.” We are designated a bother, a headache. “Shrink yourselves!” we are told.

Kaur’s poems defy that dictate. They tell young brown girls to be confident, and not to be afraid to take up space. Her poems speak freely about unruly bodies and taboo desires. Most importantly, they convey to young women that they do not need to seek approval from anyone besides themselves. This poses a tremendous threat to a world whose foundations are built on policing brown women. If we love ourselves, if we are convinced of our worth, what tools do they have to control us with?

RKP: In an essay titled “Wolves,” you and a friend are getting into a car at nighttime when two men come down the street. One approaches your friend, and is persistent even after she refuses to talk to him. You write, “For that moment, I am not myself. I walk forward…I push him. It is a hard push that says I am not afraid. I know at that moment I am not…I see fear in the man’s eyes and am delighted that I have the ability to cause fear.” Priya, I cried and cried from pride and joy when I read this story. And it makes me wonder: is this where systemic, unending violence at the hands of men has brought us? Delight at a rare and precious moment in which a woman can physically intimidate a man?

PAE: It was one of the more complicated moments of my life, emotionally speaking. I have never been an advocate for violence or physical aggression. However, in a world where women are targets of so much violence, there is an aching desire to make men see our fear. Even share it. I was completely, unabashedly proud of my ability to intimidate another human being, because he was a man.

Rape-revenge narratives, horror movies in which the Final Girl survives by killing men, these are all manifestations of that desire. So often, we feel powerless. Reading the news each day feels like an act of masochism (so many women being hurt by men). If only, for once, we could be the ones with power. It’s sad that the prospect is so intoxicating.

RKP: You’ve written a wonderful fable of sorts in the form of the essay “A Cautionary Tale for Brown Women,” in which a selfless, caring woman keeps giving away parts of herself to those in need. I think many of us have grown up seeing the women in our lives doing just this — wearing themselves thin, for children, husbands, in-laws, communities. It’s what you describe in a later essay as “an endless wellspring of care, love, and attention.” Should we be teaching selfishness to brown girls instead? Or is there a middle path somewhere, a caregiving that doesn’t suck us completely dry?

PAE: Hmm, I feel like we shouldn’t be teaching anyone to be selfish. My feminism is not “Let’s teach women to be more like men.” A world in which we all act like selfish men would be unsustainable. That being said, we do need to teach women that their needs take precedence. I think you said it — there needs to be a middle ground!

So many young brown women don’t think they have a right to put themselves first. They need to hear: “Please don’t sacrifice yourselves to make your communities happy. Nurture the people in your lives, but not at your own expense.” Equally important, brown men need to learn nurture. Young brown men have to shoulder some of that burden — that’s the only way forward.

So often, we feel powerless. If only, for once, we could be the ones with power.

RKP: Desi comedians often joke about how they’ve disappointed their parents by not becoming doctors or engineers. But this joke is often an unfunny cover story for the reality that you explore so unflinchingly in the essay “Counting Black Sheep,” which is about the countless South Asian teenagers who commit suicide under the weight of their families’ demands for “excellence.” Is this some sort of cultural disease infecting essentially all of Asia, and where do you think it stems from?

PAE: It’s the worst disease. It has such a high mortality rate across — as you say — all of Asia. Even when it doesn’t take lives, it breaks hearts. Pearl S. Buck once wrote, “Stories are full of hearts being broken by love, but what really kills a heart is taking away its dream, whatever that dream might be.” Think of all the aspiring artists, the singers, the young people who want to pursue anything slightly unconventional. We simply don’t allow them to do it. Why?

I don’t know, but I’m guessing part of it comes from a deep fear of difference. We aren’t individualists — Asian culture doesn’t value being “different” in the same way Western culture does. We are taught to respect tradition, and to endeavor to fit in. I think Asian parents genuinely believe there is only one path to success, and only one mode of “excellence.” They force their children into believing the same.

RKP: Priya, you and I went to school together for a while (!), but we only really got to know each other as adults — thanks to Twitter. And it made me smile that you listed your Twitter friends in Besharam’s acknowledgments page, because I did the same in my book. For me, the internet has been a crucial place to grow into myself. Do you think this is the case for many women of color, whose offline spaces are often tightly controlled and surveilled?

PAE: People meet me sometimes and say, “Wow, you’re so different from your online presence.” I think maybe they expect me to be as sharp and unforgiving and bold as I am online? But that’s why Twitter has been so great for me and for so many other women of color — it gives us a space to be who we can’t be IRL.

In real life, I can’t be irreverent to aunties. I can’t be sexual and unrestrained (even though I try!). For the longest time, I didn’t know who I was, because I didn’t have the space to experiment. I imagine it’s the same for many women of color — we get the chance to be free online, to try out things and personalities until we understand ourselves better.

As brown women, we are constantly exhorted to live for other people, and not for ourselves.

RKP: You write of A Little Stranger by Candida McWilliam, a novel featuring acute eating disorders, “I closed the book. It was too real; it made me feel sick.” This is very much what reading Besharam was like for me — and I mean that as a compliment! I felt a simultaneous relief and terror at knowing that if your book made me feel so seen, it would do the same for other brown girls. Am I right in saying that Besharam itself speaks from within this dichotomy — a sense of gratitude at not being alone, but also a sense of heartbreak that other brown women suffer similarly? Where do we go from here?

PAE: Thank you, I am so moved by your kind words. That’s exactly what I was trying to do.

I wrote Besharam because I felt a profound loneliness for so long. There was nobody to tell me “I feel this way too; this is why being a brown girl is hard.” Our culture encourages silence in women. We hear the eternal, pernicious, “What will people think?” Well, I’m tired of silence.

You are absolutely right: the book is written from that dichotomy. So many of us carry similar burdens, and that is heartbreaking. But the ultimate goal of speaking out is change — I think that once we feel a sense of sisterhood with each other, we can then try to make these burdens lighter for each other. As brown women, we are constantly exhorted to live for other people, and not for ourselves. Well, maybe we can subvert that teaching, and use it to help and stand up for other brown girls. That is my hope.