interviews

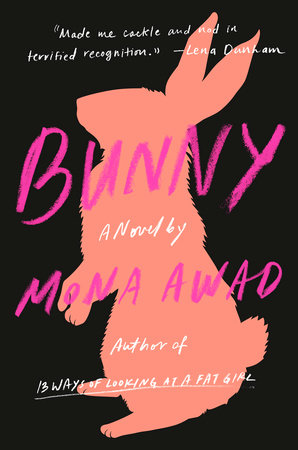

“Bunny” Shows MFA Programs for the Dark Horror They Truly Are

Mona Awad on being a boring tree murderess and finding inspiration in the comments section of ModCloth

If you’ve ever entertained dark fantasies about what really goes on at exclusive MFA programs, Bunny will fulfill your wildest dreams. If you’ve attended an MFA program and had a positive experience—as author Mona Awad did—the book will still blow your mind, though perhaps in a different direction. If you have no interest in MFA programs, Bunny will still—you see what I’m getting at.

Mona Awad’s critically acclaimed first novel, 13 Ways of Looking at Fat Girl, deals incisively with body image, self-worth, and womanhood in a series of thirteen vignettes. Her sophomore novel, Bunny, also grapples with alienation, but in a wholly different direction.

Bunny follows writer Samantha Heather “Smackie” Mackey through the second year of her MFA program at the elite Warren University. Initially, Samantha despises her cohort—four A-line-dress-wearing, “proem”-writing, Heathcliff-worshipping, upper-class women she nicknames “the Bunnies.” Her only friend, Ava—a cynical, goth-leaning artist (“dark clothes, her veil, her mesh-covered fingers gripping a cigarette like she could easily take out an eye with it”)—is the Bunnies’ antithesis. But slowly, Samantha falls away from Ava as she becomes sucked into the Bunnies’ cloying world of smut salons, mystery pills, and private, mystical gatherings they call “workshops.” The novel twists from familiar campus realism to a dark fairytale, all the while traversing the emotional highs and lows of the writing process.

A veteran of academe herself, Mona Awad has attended Brown University, the University of Edinburgh, and the University of Denver, earning her MFA in fiction, MScR in English, and Ph.D. in Creative Writing and English Literature, respectively. I normally don’t inquire too deeply about autofictional elements of anything, but I did speculate on what academic experiences may or may not have inspired Bunny’s comic horrors. And while I never attended an MFA program, Bunny still resonated with my own academic experiences: I’ve spent plenty of time watching more intellectually secure and/or better-dressed classmates clique together. I’ve always regretted my lack of invitation to secret smut salons.

Over the phone, Mona Awad and I discussed writer’s block, fairy tales, and—surely relevant to all Electric Lit readers—the frenzied coupling of terror and euphoria that comes with a creative imagination.

Deirdre Coyle: A meta-narrative runs through the novel about Samantha having writer’s block. Did you experience dry spells while working on Bunny?

Mona Awad: Oddly, no. My first book took a long time, about six years, stopping and starting. But Bunny, when I got the idea, I just kind of went with it, and I finished a first draft in three months. The story did unfold pretty organically for me, which was, given the subject matter, probably a little surprising to hear. But it’s not that I haven’t experienced writer’s block, I certainly have. The terrible thing about writer’s block, of course, is that you never really know what’s going to get you out of it. The creative writing process, and the creative process in general, is mysterious that way. There are no guarantees, so it can be a very terrifying space to occupy. I think that’s part of what generates the unease and the uncertainty, and even the horror, in the book.

DC: The speculative reveal in Bunny—when Samantha becomes aware that the Bunnies are literally practicing a kind of witchcraft—happens after we’ve already seen a lot of horror realism about writer’s block, cliques, and assholes generally. Did you always know you wanted Bunny to take a speculative turn, or did that happen as you were writing?

MA: Oh, I always knew, from the very beginning. Because I was drawing, in part, from fairy tales. And there were things about the creative process that I wanted to literalize: the idea of darlings, and killing your darlings, and the very, very complicated and often violent relationship that creators can have with their creations. The fear and the wonder and all the emotions around it—there’s just so many. It’s so ripe. To me, there is something magical about the creative process, so mysterious, and the speculative felt like it was an absolutely natural turn for the narrative to take. Fairy tales engage those feelings of wonder, too, and there’s always the possibility of transformation in a fairy tale. I thought in a book about creativity, “fairy tale” seemed like the right direction to go in. Magic was there from the very beginning, in my head.

DC: Aside from a writing MFA, what graduate programs do you think would be most conducive to this kind of horror story?

Living in my imagination and exploring my fears and my what-ifs and my desires, in narrative form, helps me cope.

MA: I think any environment in which people who are sensitive, people who are creative, are being asked to activate their imaginations at the same time, you know? Because that’s what’s generating the horror. A small group of people have been sequestered away from their usual lives, and they’re being asked to tap in to their emotions and create something. They have to do that in front of other people and expose themselves. A lot can go wrong if you really think about that situation. To me, the situation is rife with danger, rife with horror, rife with anxiety. I think that that extends even beyond graduate programs, you know? Any endeavor in which you’re putting yourself out there in front of a group of people can generate those feelings, can create that really deep unease—and can really mess with your head. That’s the other thing that Bunny plays with, this notion that perspective can really warp reality. My main character is an artist, and she is feeling very vulnerable for a number of reasons, and she’s feeling very anxious. How much of that anxiety and how much of that vulnerability is shaping the world around her, and her experience of her peers?

DC: Right, and she’s coming from a different class background than her peers.

MA: That’s part of it, too.

DC: Would you say that creative people are more prone to seeing horror in the world around them, in general?

MA: Wow, that’s a great question. If I speak for myself as a creative person, I can go in two very wildly different directions, and I can do it in a given moment. I think a lot of creative people live in their heads, they live in their imaginations, and their imaginations are really rich territory where they process the world around them. In that space, anything is possible and your wildest dreams can come true. On the other side of it, things can look really bleak, and really scary, and you can go down some really dark roads in your head. So Bunny kind of does both. Samantha has these really wondrous, exhilarating moments of creativity and of encounters with true wonder and magic and then she also has these terrifying, nightmarish experiences. You could argue that they’re both generated from the same place inside of her, that imaginative place.

DC: I think about that all the time, how the way that I see the world, and the way that creative people in my life see the world, can sometimes be…

MA: You can go pretty dark if you want to.

DC: Would you be willing to divulge any horrors from your own MFA experience?

MA: I would happily, except that I have to say—in spite of the picture that I paint of the MFA experience [in Bunny]—I finished my first novel, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, because I went to an MFA program. I had a really supportive group of people, both professors and colleagues, at Brown, and actually, the experimentalism, which I think Bunny takes a bit of a jab at—even though it is kind of an experimental book—helped me write 13 Ways. It helped me get outside of my own ideas about how a story was supposed to be told. So it shook me up in ways that were very productive, but certainly, as a creative person, just trying to finish this book, I had a lot of anxiety. I almost dropped out in the middle of my MFA—and it had nothing to do with Brown or my peers or anything like that. I just didn’t think I was going to finish my book. And that was awful. So probably some of the writer’s block stuff that Samantha has, that’s where some of my horror stories come from, just getting in my own head and thinking that there was no way I could finish this book. And it mattered so much to me, you know? The book mattered so much to me, and this idea that I couldn’t finish it was just so scary. But then, of course, I did finish it, in part because I did stay, and I told myself that I had to at least stay and try. And if I stayed and tried, at least I’d gone through the program.

Probably one genuine experience of horror that I had—and this is definitely in the book, to some degree—was my surprise at how sketchy Providence was. I’m glad, in a way, that I had that experience, because it’s such a beautiful town. The houses are stately, even in their ruin. It’s a stunning place. I can see why H.P. Lovecraft was so inspired by it and had such a profound creative relationship with it. But it’s also kind of creepy. There’s a real divide between the Ivy bubble of Brown and RISD, and then the town beyond that. That took me by surprise, a little, even though it is a lot better than it used to be. It was kind of scary. It was useful, too, in Bunny—it inspired me to draw from those social, class differences, and really bring them out in the book and really use that as a way to generate a sense of unease in the reader, and a sense of the Gothic. The horror, in part, comes from the setting. It’s very, very charged.

DC: We kind of see that where Samantha and Ava live, versus where the Bunnies live.

MA: Exactly. Very different parts of town.

DC: Clothes signify so much in Bunny: personality traits, lifestyle changes, even betrayal. I loved the descriptions of Ava’s outfits, and her black veil. She’s very much my personal style icon. And then on the Bunny side of things, I liked the dress covered in kittens “wearing crowns because they are the kings and queens of this world.” What kind of “research” did you do to make these sartorial details so sharp?

MA: Oh, yeah. First of all, I’m obsessed with clothing. It’s a very charged thing for me, and it’s always been a source of inspiration for me, in my first book and in this one. Maybe it’s because of my own struggles with body image, but I have a very, very layered relationship to clothing. So I’ll pay attention to clothes, a lot of attention.

I feel like a boring tree murderess very often. Why put it out in the world if it’s never going to be as good as a tree?

For the creepy-cute outfits that the Bunnies wear, I was really drawing from that kawaii idea of the cute being a little monstrous. One site that I did visit a lot was the ModCloth site. I looked at the comments a lot. Because in the comments, people reveal the things that they hate, but they’re trying to accept that they still love the dress, and they don’t want to part with it. There are such interesting little monologues that reveal so much about the very layered conflicts that people have with their clothes. I tend to look at the comments on dress sites, not just on ModCloth, to get inspiration. And I love the names of the ModCloth dresses, I think they’re hysterical. They have such outlandish names.

Then the darker, more vintage, glam, punk aesthetic that Ava has—I love those looks and I love the subcultures associated with those looks. So it was fun for me to kind of go crazy describing Ava. She’s totally the antithesis, obviously, of the Bunnies and their kind of fashion.

DC: The description of Ava’s apartment made me feel like she was living in my dream apartment (“this living room that smells like a thousand old frankincense sticks…The turntable playing tango or some weird French sixties stuff that sounds exactly like the music you dream of but can never find. The lady-shaped lamps lit all around us”).

MA: I know, right? It’s my dream apartment, too.

DC: During one of Samantha’s inner monologues during workshop, she imagines one of the Bunnies saying, “I’m sorry that I think I’m so goddamned interesting when it is clear that I am not interesting. Here’s what I am: I’m a boring tree murderess.” I’ve been thinking about this a lot because I relate to it so deeply. Do you have any advice for those of us who feel like boring tree murderesses most, if not all, of the time we sit down to write?

MA: I mean, I would want to take [that advice] too, because I feel like a boring tree murderess very often. I always think, ‘Is this as good as a tree?’ It’s never going to be as good as a tree. Why put it out in the world? We need trees. I don’t know, I think—oh. It’s so hard, isn’t it? The tree murderess comment aside, it really is true that being creative is essential to engaging with what it is to be alive. So I think that’s where the permission has to come in, you know? It’s like, this is my way of actually being alive, and communing with something beyond myself, communing with the world. That’s what I always try to tell myself: that living in my imagination and exploring my fears and my what-ifs and my desires, in narrative form, helps me cope.