Books & Culture

‘Call Me By Your Name‘ Finally Shows the Kind of Bisexual Narrative I Want to See

Both book and movie take a nuanced view of queer sexuality

I ’ve gotten used to the fact that I can’t talk about women with my straight female friends the way I can talk about men. When I talk about men, my friends hum with encouragement, bubble with excitement over the possibility of what could happen. They give their seal of approval (“he works for Goldman? Nice”) or disapproval (“his mattress is on the floor!? Honey…”), eager to share their own dating triumphs or horrors. In turn, I’m genuinely eager to hear them, but they can’t relate. It’s a one-sided conversation, almost like a diary entry.

Years ago I began to retreat to literature and film to find similar narratives to mine. It was easy to find such on the fringe, in indie films that premiere at small festivals and novels deep within my college’s library. When it came to movies I can see in my hometown movie theater, the ones that are buzzed about for months by everyone from critics to subway commuters, I often came up short. The characters were predominantly straight, rarely gay, never bisexual. I never saw a mainstream film that reflected my experience until Call Me By Your Name.

The characters were predominantly straight, rarely gay, never bisexual. I never saw a mainstream film that reflected my experience until ‘Call Me By Your Name.’

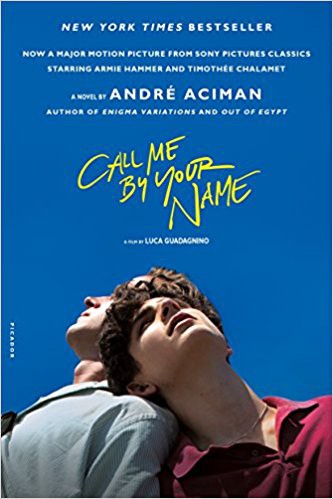

Every year, one LGBTQ movie seems to generate enough buzz to make its way into the mainstream. The pinnacle of this was Moonlight, which not only made back its budget over ten-fold, but it took home the Oscar for Best Picture. Last year that singular movie was Call Me By Your Name, based on the 2007 novel by André Aciman. Watching the trailer and reading early reviews about the film from the Sundance Film Festival compelled me to get my hands on the source material before seeing the film.

Elio, an Italian teenager, is the narrator of the story. During one summer in the 1980s, a Columbia professor named Oliver stays with him and his family. Part 1 of the novel is an incredible build-up. Elio and Oliver meet each other, and Elio is instantly enamored (as is Oliver with him, though the reader only sees Elio’s side). At times, Elio is so peeved he has this unobtainable crush that he talks about killing Oliver, then himself. There’s a line in the beginning of Part 2, though, that struck me more than anything:

Did I want to be like him? Did I want to be him? Or did I just want to have him?

I froze. I reread the line 10 times. This was the first time I’ve had my thoughts read back to me. Elio had just been waxing poetic about Oliver’s muscular shoulders while being incensed that he was apparently sleeping with a multitude of women around town.

For the first time, I found my experience validated by the dance I was seeing on screen. The way I’m attracted to women is inherently different than my attraction to men; it’s difficult to process alone, in my head, without anyone to talk to. The line between attraction and admiration to women is one I walk almost daily. It’s sharing a glance with a fellow commuter on the 6 train. It’s an Instagram photo suggested to me on the explore page, a woman draped in natural light in her bedroom. Do I want to be with this woman, or do I want to just be her? This ambivalence is something I experience often, but I don’t share it with anyone — and here it was repeated directly to me in this book.

This ambivalence is something I experience often, but I don’t share it with anyone — and here it was repeated directly to me in this book.

Elio and Oliver do sleep together. All the while, Elio also sleeps with a woman named Marzia. At one point, he balances sexual relationships with both of them:

Barely half an hour ago I was asking Oliver to fuck me and now here I was about to make love to Marzia, and yet neither had anything to do with the other except through Elio, who happened to be one and the same person.

This occurs several times in the novel, where Elio compares Oliver and Marzia. Elio kisses Oliver the way he kisses Marzia; the way Oliver smells like the sea reminds him of the way Marzia smelled.

Elio and Marzia’s relationship eventually fizzles away, but not before numerous sexual encounters and dates. They never have a proper goodbye. Rather, Elio rushes to Rome to be with Oliver.

It’s clear that Elio was in love with Oliver and not with Marzia. This isn’t because Marzia wasn’t a man, though. It’s because she wasn’t Oliver.

It’s clear that Elio was in love with Oliver and not with Marzia. This isn’t because Marzia wasn’t a man, though. It’s because she wasn’t Oliver.

Stories that are made into mainstream LGBTQ films tend to have similar narratives. The protagonist has experienced only hetero relationships, along with a void that’s always been there. They feel disdain: with themselves for feeling this way or with their partner for not filling that void.

Such is the case with Brokeback Mountain (the mainstream queer movie of 2005) and with The Price of Salt, on which the film Carol (the mainstream queer movie of 2015) is based. In Brokeback, Ennis and Jack are drawn together despite impossible circumstances, as are Carol and Therese in Carol.

The spouses in those stories are antagonists. Who can forget when Michelle William’s Alma spits out, “Jack nasty!” in Brokeback or when Kyle Chandler’s Harge demands custody for his and Carol’s child.

‘Call Me By Your Name’ Made Me Realize What the Closet Stole From Me

But Marzia isn’t an antagonist in Call Me By Your Name. If anything, she is a distraction Elio willingly takes when he thinks he and Oliver won’t ever go beyond acquaintanceship. Even after the two men consummate their relationship, Elio keeps up his fling with Marzia. While Elio is never in love with Marzia, he is genuinely attracted to her physically and sexually. If anything, I’d argue this shows how layered Elio’s sexuality is. Is he homo-romantic and bisexual, or bi-romantic as well? Regardless of the answer, his orientation remains more complex than other LGBTQ characters in mainstream lit and film.

In other narratives, the character then meets their “person,” someone of the same gender. The void is filled, but not for long. Due to societal pressures or deep-seated self-hatred, the two don’t end up together. One (or both) may die, and they’re ultimately miserable if they live.

Brokeback Mountain is a clear example of this. Jack’s line, “I wish I knew how to quit you” prompts Ennis to insist he’s “like this” because of him. Their sexualities are afflictions, mars to their characters that they want to be without. Jack eventually dies, and Ennis cries into his blood-soaked shirt.

Brokeback is the first “gay movie” I remember seeing. I was maybe 11 or 12, and the concept of sex scenes, let alone gay sex scenes, was still taboo. I was alone and told no one that I watched it; I don’t know if I meant it to be a secret, but it remained one regardless.

In my rewatchings of Brokeback (and readings of the short story on which it’s based), I feel the same disconnect I did at that age. I was watching people that were far away from me, both in location and mindset. They were gay and ashamed. They were trapped in their marriages yet repulsed by the only person who gave them joy, another man. I couldn’t relate.

In my rewatchings of Brokeback Mountain, I feel the same disconnect I did the first time. I was watching people that were far away from me, both in location and mindset. They were gay and ashamed. I couldn’t relate.

My first experience watching Carol was much different than that of Brokeback. I saw it where it premiered to critical and audience acclaim, the 2015 Cannes Film Festival. I was almost 21, secure in my queer identity and excited that I would not only see a celebrated film with queer characters, but queer women at that.

Upon viewing, though, I felt that same disconnect. There was a lingering sense of shame, of detestment towards Carol’s family — and Carol’s husband, too, was as vitriolic as the wives in Brokeback.

In The Price of Salt, Carol is stripped of everything because of her sexuality. Not only can she and Therese not be together, but she allows her abusive husband to get what he wants out of fear of being found out. She lives, but what kind of life is she left with? The novel ends on a hopeful note, but it’s ambivalent at best and tragic at worst.

Brokeback Mountain and The Price of Salt are in the gay literature canon, and they should be. I’m not arguing that they aren’t stories that should be told. It’s also very true that queer people throughout history (and in the present day) have experienced the intense pain that these characters have, and this pain should be projected on screens in thousands of theaters across the country.

But there are so many more stories to be told. Stories that I relate to should be projected on those screens, too. I don’t have the comfort of hearing them in my real life, of exchanging stories with friends over wine or Facebook messenger — and I know I’m not alone.

It’s true that queer people throughout history have experienced intense pain, and this pain should be projected on screens. But there are so many more stories to be told.

If anything, what I see about queerness online is concentrated on how people (men) are trying to push a new identity into the lexicon: “mostly straight.” It’s so pervasive, in fact, that there’s a new book all about the term — and more men identify as “mostly straight” than either gay or bisexual.

The concept is one that frustrates me, but doesn’t shock me: men who are not straight but also not gay would rather identify as predominantly straight than queer, or bi, or anything else. It encourages a binary in sexuality: there is either straight or gay. The fact that I live in this gray area is somehow an additional other. Reading headlines like “More Men Than You Think Identify As ‘Mostly Straight’” makes me question myself again, reinforces the loneliness I feel.

I picked up Call Me By Your Name to feel less alone.

This book does retain some of that classic narrative. Elio and Oliver don’t end up together. The unfortunate part of the novel is that they only share that summer — as Ennis and Jack only share Brokeback Mountain — but it didn’t destroy Elio’s life.

When they are together 20 years after their whirlwind relationship, Elio’s flooded with memories. He wants Oliver to call him by his name again. It’s bittersweet, it’s melancholic and the reader can’t help but think “what might have been”…but Elio isn’t crying into Oliver’s shirt.

One fundamental difference is that Elio’s goes went on without Oliver. There’s also no sense of him wanting to “quit” Oliver, of seeing his sexuality as a burden.

Years after the summer they spent together, Elio reflected on his life post-Oliver and “the people whose bed [he’s] shared”:

Fancy this, I might say: at the time I knew Oliver, I still hadn’t met so-and-so. Yet life without so-and-so was simply unthinkable.

People. The people Elio’s shared his bed with. “So-and-so” is genderless. Elio’s coming-of-age that summer was a distinctively queer one, not a gay one.

Of course I don’t know if this was Aciman’s intention. I don’t know if he set out to buck the trends of Brokeback Mountain, Carol, and other mainstream queer stories, which are so often gay stories. Perhaps I’m projecting my own desire to read a character like me onto this novel.

I want a lot of things out of queer media that will take years to obtain, maybe beyond my lifetime. I want more than one LGBTQ film a year to be celebrated by the mainstream media. I want more protagonists like Elio. I want more female protagonists like Elio.

I want more protagonists like Elio. I want more female protagonists like Elio.

Upon seeing Call Me By Your Name, I was delighted that it remained mostly true to the novel. What was left out was the last section, which takes place 20 years after Elio and Oliver’s summer together. The film left out the fact that Elio fell in love with people other than Oliver, but nonetheless kept his encounters with both Oliver and Marzia. And thankfully, Marzia still wasn’t an antagonist.

The film is now part of the group adapted from LGBTQ literature that have reached awards recognition. That group is unfortunately small, but CMBYN nonetheless separates itself in its portrayal of sexuality. But I still want more characters whose sexual fluidity is apparent and explicit like Elio’s. I want them to acknowledge that gender doesn’t determine attraction and that sometimes there’s a gray area between lust and reverence, and that’s okay. I want stories where queer isn’t synonymous with gay. I want “mostly straight” characters to acknowledge they are queer and accept, maybe even love, that about themselves.