Craft

Carrel: A Writer Regenerates in the Stacks

Re

Rebirth during the Yale Writers’ Conference

Sunlight, filtered through Tiffany stained-glass, dappled the audience’s backs with patches of red, green, and gold. The brethren, eager young writers attending the Yale Writers Conference of 2014, were tuned in to a panel of literary agents who intoned words of advice from the stage. Reverently, the writers scribbled in their Moleskin notebooks about agent commissions and editorial preferences. I doodled in mine. Next to me a fireplace, obviously non-working, displayed miniature international flags poked into a wooden base. Not on the hearth but in the fire box. Was this a global warming statement? A critique of patriotism?

After the panel members had left the stage and conference attendees filed through the double doors, I remained in my little wooden desk. The conference director and his cheerful blonde assistant were collecting books and papers that had been left on the long table. I felt like the Mason jar of wilted hydrangea heads that perched on the podium. My nose tingled, and I sensed tears coming. I would not cry in front of the Director of the Yale Writers’ Conference, but I couldn’t leave without speaking to him or his assistant; I was friendly with both and that would seem rude. I’d say a quick ta-ta and scoot out. The director turned around just then, said hello, and I began to bawl. Bawled for my unpublished state. Bawled at abandoning poetry after rejections from lofty journals I had no business submitting to. Bawled at many, many missed opportunities to write while children napped or were at school. But mostly I cried because I didn’t want to be what I was: an older would-be writer wounded by the blade of bitterness.

I would not cry in front of the Director of the Yale Writers’ Conference, but I couldn’t leave without speaking to him or his assistant; I was friendly with both and that would seem rude.

All during the conference I had attended the panels and workshops but had avoided anything social, instead sulking back to my hotel room chock full of self-pity. My movements were militaristic, a series of engagements and retreats. The friendly young lady at the hotel front desk waved to me at each of my departures and returns. Behind her smile, surely she questioned my sanity, and honestly, I did feel a little crazy. And so it was to save my sanity, or at least gain some equanimity, that I took off toward the library.

On my way there, I walked past stone-faced Berkeley College, where my husband lived for three years as an undergraduate. I recognized it by the crest above its doorway; in the early days of our marriage I used to wear his old Berkeley t-shirt, emblazoned with that crest, which was shaped like a knight’s shield with ten white crosses marking its brilliant red background. It was a great-looking t-shirt, but I must confess that by wearing it I hoped people would assume I had gone to Yale instead of my mediocre women’s college in Virginia.

Along the side of Berkeley, a slate walk led the way to Sterling Memorial Library, and as I trod it, my competing emotions were a-boil: exhilarated at being at the Yale Writers’ Conference, weighted down by the heft of the whole Yale thing, excited for the next ten days of hobnobbing with well-known writers, and other feelings I couldn’t label at first but soon came to recognize as loneliness and uncertainty. Oh, I should probably add a festering dab of self-doubt.

The pathway emptied onto a flagstone plaza overlooking a wide expanse of grass, a quilt of worn and seeded squares, no doubt caused by Frisbee games, or whatever outdoor game is popular with 21st century Elis. I stopped at Maya Lin’s water sculpture The Women’s Table, an elliptical slab of polished green granite balanced on a black granite base. A skin of water slid over it. Under the water, a spiral of incised dates and numerals shimmered. The dates commemorate the early years of women’s admittance to the college, and the corresponding numerals tally each year’s matriculating females. Beside 1969, the first year of women at Yale, the numeral 576 is etched. That group’s trepidation, expectation, and excitement must have been not unlike my own.

Beside 1969, the first year of women at Yale, the numeral 576 is etched. That group’s trepidation, expectation, and excitement must have been not unlike my own.

Behind The Women’s Table, a seven-story stack tower hulked over a neo-Gothic facade, which was so ornate that I stood for a while, agape. The top is crenellated like a medieval castle’s ramparts and seems to protect an immense pointed-arch window below. Above the entry doors, mid-bas reliefs presage the building’s scope contained in its four million volumes. One relief shows a wounded bison, mammoth, and a bone pendant from Magdalenian-era caves in the Dordogne region of France; think Lascaux. A Viking ship, Assyrian scribes, and Egyptian stonemasons also speak to the world’s civilizations housed within. One inscription quotes Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound. Translated from the Greek, it reads:

Ignorant they of all things till I came

And told them of the rising of the stars

And their dark settings, taught them numbers, too,

The queen of knowledge. I instructed them

How to join letters, making them their slaves

To serve the memory, mother of the muse.

How to join letters…I thought of my second-grade teacher, a nun, scraping a funny-looking contraption across a blackboard. When teaching us handwriting, she used this gadget, comprised of a flat wooden slab from which projected three wire prongs that had curlicues at their ends bearing sticks of yellow chalk. After chalking the lines on the blackboard, Sister Christine would take a felt eraser and with lightning quick flicks of her wrist erase parts of the middle line. Hyphen-high, for lower-case, she’d say. It occurred to me that most of my fellow conference attendees were too young to know about any of this: nuns? handwriting? blackboard? Aeschylus’s quote, with its mention of ‘mother, niggled me — — many of these young writers were the same age as my children.

When I ventured into the library, I nearly genuflected, its structure was that reminiscent of a Gothic cathedral: coffered ceilings, soaring vaults, wall-sized stained-glass windows, cinquefoils, crockets, and gargoyles. The only thing missing was incense. I moved into the central area, which was like a nave, the atmosphere light and airy yet grand. Because of the exaggerated height and sunlight beaming through the windows, one’s gaze is pulled upward; in medieval cathedrals this suggested heaven, at Sterling, knowledge.

When I ventured into the library, I nearly genuflected, its structure was that reminiscent of a Gothic cathedral.

Activity was a-thrum: susurrus of docents leading tours, a printer sighing, echoes of boots, squeaks of running shoes. All of it lifted my spirits. Libraries usually have this effect on me, but what I really came for was the serenity of a carrel, snugged in among shelves of books.

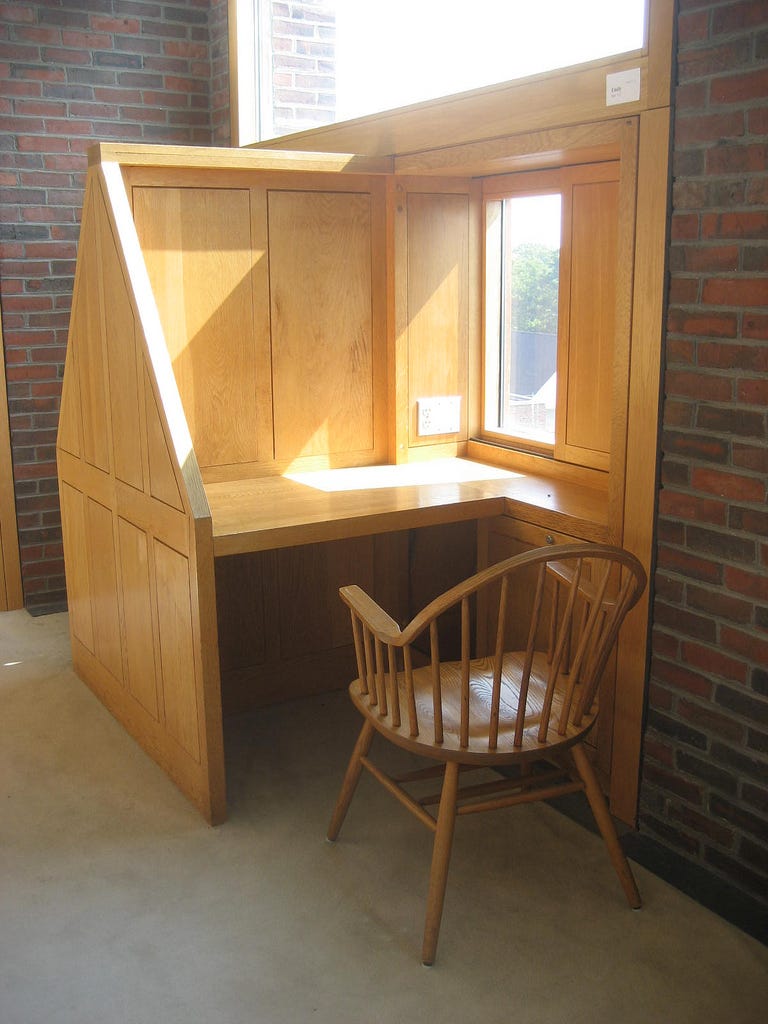

After procuring a temporary stack pass, I was beginning to feel less like a visitor, expertly swiping the pass at the security desk, jabbing the elevator button that would deliver me to the seven-story stack tower, and ultimately to a carrel. To me, a carrel reprises what I imagine the womb’s atmosphere to be — one of comfort and safety. We can think of our mothers’ wombs as our first carrels. A carrel, too, functions like a womb; transformative creation happens in both. In a womb, a zygote becomes a human being; in a carrel, ideas, observations, hypotheses become stories, poetry, theories.

To me, a carrel reprises what I imagine the womb’s atmosphere to be — one of comfort and safety. We can think of our mothers’ wombs as our first carrels.

As the stack tower security guard inspected my Yale Writers’ Conference tote, ZZ Packer’s short story “Drinking Coffee Elsewhere” surfaced in my thoughts. The story relates the experience of a young black girl trying to assimilate at Yale during her first year. It’s a lonely story, but parts of it are hilarious: the first scene depicts her in a getting-to-know-one-another game of “Trust” where one person stands inside a circle of her peers, who instruct her to fall backwards into their arms. “No, way,” her character says. “The white boys were waiting for me, sincerely, gallantly…No fucking way.” I fully empathized with Packer’s character, except I was neither young nor black; I was a sixty-one year-old white woman amidst a youthful multi-cultural crowd, who, I assumed, could write me under the table.

The elevator trembled up to the sixth floor where I got off in search of the perfect carrel: lit by a window and in a corner. I found one on the fourth level, eased back into its Windsor chair, and just sat for a minute, relieved of that awful feeling of not fitting in, an interloper. Silence prevailed; solitude reigned.

In his Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard pinpoints the relationship between solitude and creativity:

“And all the spaces of our past moments of solitude, the spaces in which we have suffered from solitude, enjoyed, desired, and compromised solitude, remain indelible within us and precisely because the human being wants them to remain so. He knows instinctively that this space identified with his solitude is creative…”

With my pencil of choice, a Mirado Black Warrior, I wrote the date in the corner of a blank page in my notebook. That’s as far as I got. The graffiti on the upright back of the desk had caught my attention: a Mandarin character that resembled a lantern, a large block of Spanish, and some very interesting commentary. Someone had scrawled, with elaborate tails on the ys and ps, existential thoughts about carrels: “You realize that this carrel will be perpetually assigned.”

Someone had scrawled, with elaborate tails on the ys and ps, existential thoughts about carrels: “You realize that this carrel will be perpetually assigned.”

Another carrel-occupier had replied in block print: “I like the idea of there being no definite ownership only anonymous and arbitrary possession of this place.” A third person, with letters that leaned left, had written something that matched my emotional state: “Man is destined to be a stray…” I recorded all of this in my notebook and circled the last bit, then began writing. I wrote that yes, if man were a stray, then writers are doubly so. Writing is solitary, and the urge to write, in fact, is akin to a stray’s search for sustenance. Writing is foggy and murky. Yet the act of writing somehow marks a way out of the fog, rendering both writer and reader temporary shelter. Somehow this happens. I haven’t a clue how but am pretty sure that staying at your desk for long periods of time has something to do with it.

The word carrel derives from the Medieval Latin carula; or perhaps from the later Latin corolla “little crown, garland.” Eventually both words evolved to “carol,” an allusion to the sound of monks reading aloud the manuscripts they were working on. During the pre-Renaissance period, there was an unprecedented need for copies of books, the laity having become increasingly literate. During 14th century England, eighty percent of adults could not spell their names. Carrels also sequestered the monks from choristers practicing in the nearby choir. Imagine a monk in his chilly, poorly-lit carrel bent over, quill in hand, scratching and pricking at vellum. Most likely a teen-ager whose eyesight was still keen, he’s painting minuscule, intricate, and complex illuminations: blue-winged serpents entwining the pillar of a P, a tiny naked human riding a dragon in the open loop. Then imagine a choir practicing Benedictine chants over and over, and it’s no small wonder that carrels were invented.

The Rites of Durham is a mid-sixteenth century anonymous account of monastic life in England’s Durham Cathedral. A manuscript roll, sixty-seven feet in length, six inches wide, it consists of sixty-five pieces of paper stitched together with thread. When I first saw an image of the Rites, I couldn’t help but think: This is a roll of toilet paper. (Useless bit of the arcane: the width of a modern toilet paper roll measures five inches.) In the Rites’ description of the physical layout of the Cathedral, the carrels’ location is noted:

“In the north syde of the Cloister, from the corner over againset the Church dourthe Dorter Dour, was fynely glased from the hight to the sole within a little of the grownd into the Cloister garth. And in every wyndowe Pewes or Carell’s…” which are described as “fynely wainscotted and verie close…in every carrell was a deske to lye there…” and continues with the monks’ postprandial retreat back to the scriptorium: “…when they had dyned, they dyd resort to that place of Cloister, and there studyed upon there books, every one in his carrell, all the after nonne, unto evensong tyme.”

It’s almost as if the monks had been tucked in for a nap.

The summer before fifth grade, my father challenged me to read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I remember bonding with that book, flicking the page corners, which made a sound like shuffled playing cards. I cared for it, always using a bookmark, never turning the corners down or, worse, laying it spine-breakingly face down. After completing a chapter, I would close the book, finger-tracing its incised letters on the cover. I can call up exactly what that book looked like: green cover, the H and F designed out of rickety fence posts.

I remember bonding with that book, flicking the page corners, which made a sound like shuffled playing cards.

Inscribed above the left door of Sterling’s entrance, there is a translated Egyptian passage from a Middle Kingdom papyrus: Would that I make thee love books more than thy mother. Of all the quotes above the main doors’ lintels, this one left me quite smitten. In my life I have loved other books the way I loved Huckleberry Finn: Robert Lowell’s Life Studies in Goucher College’s Julia Rogers Library; Ignatius Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises in Johns Hopkins’s Eisenhower Library; and most recently Jayne Anne Phillips’s Black Tickets at the Scottsdale Public Library. All I read in a carrel.

Relying on my sketchy Spanish, I tried to translate the large block of writing. No te amo, I do not love you, si fueras rosa, something about a rose? My translating stalled, I counted the lines and realized that I was reading a sonnet. It was Pablo Neruda’s “Soneto XVII”, a stirring love poem, one of a hundred from his 1959 Cien Sonetos de Amor. Who was the romantic who marked the desk with such gorgeous words? Was it written for a particular someone the writer knew would sit in this carrel? Despite the scribe’s anonymity, I perceived an intimacy between the two of us. Courtesy of Google, I read an English translation of the poem. I reread the last four lines aloud:

So I love you because I know no other way than this:

Where I does not exist nor you,

So close that your hand on my chest is my hand,

So close that your eyes close when I fall asleep.

The erasure of the two selves in the second line creates a selflessness, the kind of selflessness that allows for true communion between the I and the you of the poem. The speaker only knows one way to love the beloved but does not define “the way” and instead elevates the “where”, the place. In my place, the carrel, I imagined I was the speaker and the spoken to “you” was my writer self. Why not? As Bachelard wrote, a place of solitude is a creative one. An anonymous writer had left a gift for whoever came to that carrel. I was grateful to have chosen it and to have received a sonnet. I was grateful for the inspiring graffiti. I was grateful to be at the Yale Writers Conference. Tired, I checked my watch and saw that I had been writing for nearly two hours. Up in the Sterling stacks, I had regenerated my writer self, floating within the amnion of my carrel.