interviews

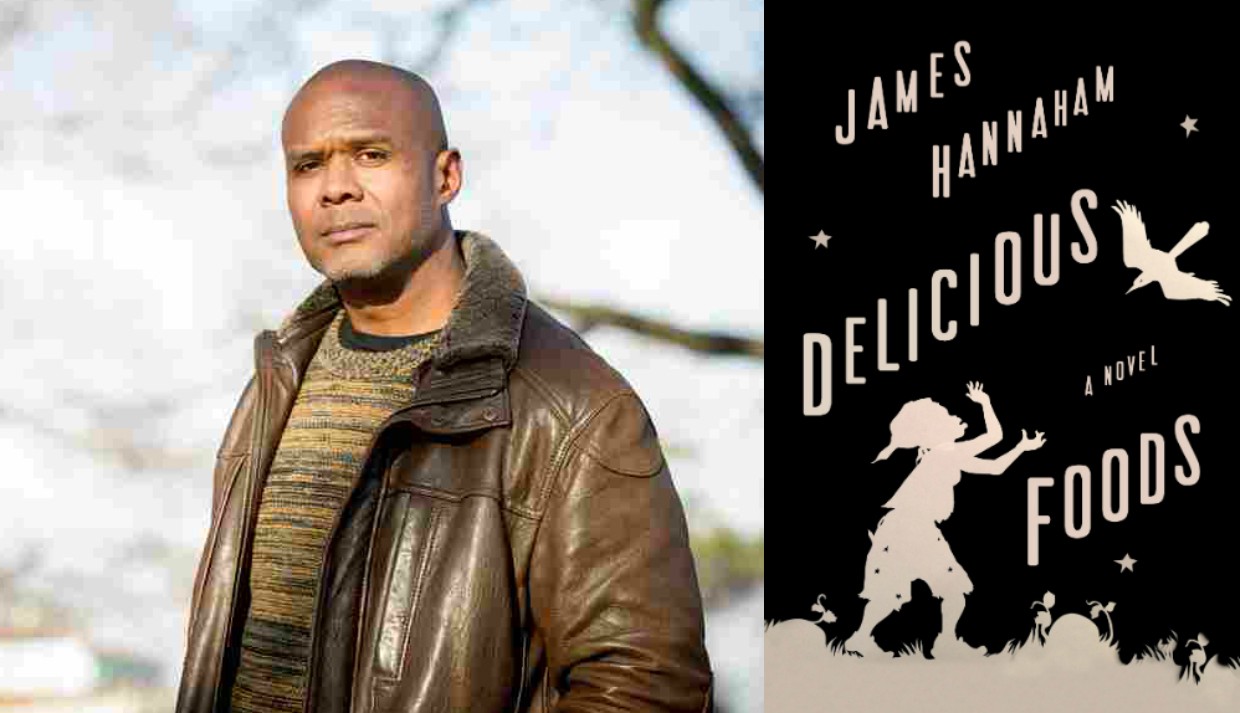

Catching Up With The Eagles Prize Finalists: James Hannaham, Author Of Delicious Foods

This fall marks the inaugural award of the Brooklyn Public Library’s Eagles Prize, recognizing “the best books of the past year and the authors who most embody Brooklyn’s ideals.” Nominations were made by the borough’s bookstores, librarians, and library supporters. The Library announced a shortlist of six authors–three for fiction, three for non-fiction–over the summer. The winners, chosen by a panel of local authors, will be announced later this month. In the lead-up to the announcement, we decided to ask the finalists a few questions.

Next up: James Hannaham, Brooklyn resident and author of the novel, Delicious Foods (Little, Brown and Company, 2015).

(We also spoke with Hannaham and Jennifer Egan in March, when Delicious Foods was released.)

Adalena Kavanagh: As a writer, what’s your relationship to Brooklyn and its literary history?

I mean, I’m more of a fan of Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones than I am Walt Whitman…

James Hannaham: The Hannaham side of my family has lived in Fort Greene for more than half a century. Circa 1953, I think, my grandparents bought a townhouse at Vanderbilt and Dekalb for the whopping sum of $11K. My father grew up there, and two of my cousins on that side still live in the house. I have various other relatives scattered around the borough from both sides of my family. I’ve been teaching at Pratt for about 9 years now, and nearly every day I pass by the house and think about its past, sites my dad and his siblings might’ve visited, and how much time I spent on the stoop as a kid, looking at Piro Funeral Home, which is one of the few businesses that has remained in that area since then. My parents split when I was quite young, but my father lived in Cadman Plaza in Brooklyn Heights back in the 70s when it was Mitchell-Lama housing, and later on Jay Street, and though I grew up in Yonkers with my mom for the most part, I spent a lot of weekends in the area with my dad. Then, pretty much coincidentally, I moved to Fort Greene in 2001. My relationship to Brooklyn’s literary history is actually less intense than my filial ties. I mean, I’m more of a fan of Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones than I am Walt Whitman — though I did go to a junior high school in Yonkers named after Whitman, and every day I had to walk past a Whitman quote etched into its concrete wall: “The main shapes arise!/Shapes of Democracy total, result of centuries/Shapes ever projecting other shapes.” It sounds somewhat ominous now, considering Yonkers’s history of housing and school segregation and the fact that the school got shut down the year I graduated because it had toxic levels of asbestos insulation in the walls and ceilings. It sat empty for at least a decade afterward. No more shapes arising out of that hell hole.

Kavanagh: What do you want to see more of in the literature of Brooklyn?

Hannaham: I wish I could answer that question with any degree of specificity. “The Literature of Brooklyn” is a rather large category, one that can encompass anyone from H.P. Lovecraft to Monique Truong. So with those two writers as guideposts, I guess I’d have to say do away with Lovecraftian cryptoracist subtext, and more fiction with a sensual relationship to food?

Kavanagh: Your novel, Delicious Foods, is about an ill-fated civil rights activist couple and the long-term effects of systemic racism and addiction, yet you approach the material with grim humor. Why did you take that tone and approach?

But it has embedded in it an uncomfortable truth that no one wants to hear about their society: You are complicit with evil shit like this.

Hannaham: Why indeed! Aside from the fact that I have a tendency to approach my entire life with grim humor, as you know from taking a class with me, I believe this to be the tone that the universe takes with humanity. I think I had written myself into a corner, essentially. I’d decided that this subject matter was extremely important to me and I felt that it had the power to change the conversation about slavery that I’ve grown so frustrated with, the one that fails to acknowledge that these kinds of things are still very much present, literally, and that the system we have in place works by keeping everyone blissfully uninformed about whose labor has created what earthly pleasure or luxury item or what have you. But it has embedded in it an uncomfortable truth that no one wants to hear about their society: You are complicit with evil shit like this. I don’t even care to hear that myself most of the time. So I thought, well, humor is a good way to sneak such messages across the demilitarized zone. And a good bit of that decision has to do with my cousin Kara Walker’s work, and her way of approaching difficult material, often related to slavery, by indulging some of the most outrageous, scathing, inappropriate humor and bad puns and bad taste one can find in contemporary art. I dedicated the book to her, and to my bestie Clarinda Mac Low, because the ideal dedication for me is a way of saying, This book could have arisen from a private conversation between you and me.

Kavanagh: I don’t want to give any spoilers, but you give voice to a character that is technically an inanimate object, but has the power to wreak havoc on the lives of his “friends”. When in the writing process did you come up with this particular concept? Why his specific voice and diction?

Hannaham: Ah yes, Scotty. (Don’t worry about spoilers. The book is deliberately full of spoilers, because I had gotten into this idea that I find fascinating, which is that you can tell the reader what’s going to happen in a story and that actually creates interest, because we don’t read for “plot” as much we want to know about process.) Anyway. I had started writing a close third on a drug addict, Darlene, because it didn’t make a whole lot of sense for an addict to be lucid about her experience, certainly not in a sharply observed, novelistic type of way. At the time, Darlene was going to be from a different social class and this black vernacular voice was going to stand in for her thoughts, I suppose. But then I decided to make Darlene someone who had had some chances and was squandering them through her addiction, but I still had this voice, and I’d really enjoyed writing it. So I had to ask myself, Who is speaking, exactly? And one of the answers I came up with was that it was the drug itself talking. And then that move, as shameless as it was, also made the book less difficult for me to write both in terms of my enjoyment and the difficult material and filled it with sick humor, which is apparently like jet fuel for my muse. I was relatively sure people would be repulsed and horrified, but it turns out that a lot of people really love crack cocaine.

Kavanagh: At the end of the novel you write from the point-of-view of a character named Sirius, “A story might help you get through your life, he said, but it doesn’t literally keep you alive — if anything, most often people who have power turn their story into a brick wall keeping out somebody else’s truth so that they can continue the life they believe themselves to be leading, trying somehow to preserve the idea that they’re good people in their small lives, despite their involvement, however indirect, with bigger evils.” The character has been exploited and escaped from a traumatic experience, and he names the collective societal delusion and willful blindness to injustice, “stories”, which reads as an admission that there is only so much writers can do, or are willing to do, in the face of bigger evils. As a writer, how do you answer Sirius’s observation (if you can, at all)?

Hannaham: Technically I’m not writing from Sirius B’s perspective at that moment. In an earlier draft, I did do that, but it seemed wrong to end with him rather than Eddie and Darlene, so I rigged up this trick where I had the two of them talk about Sirius instead of getting the story straight from the horse’s mouth. But that’s sort of inside baseball. All Sirius is saying is that stories aren’t food, shelter, or water. I can’t help but agree with him on that. And I suppose he’s also making the point that stories can guide you or they can ruin you. They can be philosophies, delusions, or both. What matters ultimately is your relationship to them, the way you react to them, not merely their presence or their content. And beyond the explanations we come up with for what purpose we serve on Planet Earth, a brain-stem kind of will to exist is what actually prevails. All that to say, I think the brother has a point.

I’m not sure why more people don’t often openly acknowledge this, but art follows politics, not the other way around. Art is made in a political context and people view it in that context whether artists want them to or not. Imagine, for example, all the great works by LGBT authors we could have in countries where homosexuality is punishable by death if their political climates became tolerant. I’m not saying that writers can’t work for change, and certain types of writers — journalists especially — can help transform the way we see our political contexts and occasionally kick us off our rusty dusties. But it’s rare in our day and age that a work of art actually changes its political context in a direct, measurable kind of way. Like it raises awareness enough to get unjust laws changed. I mean, the only two novels I can think of that have directly made a huge difference are Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Jungle, the more recent of which came out 110 years ago.