Interviews

Choose Your Own Dystopia

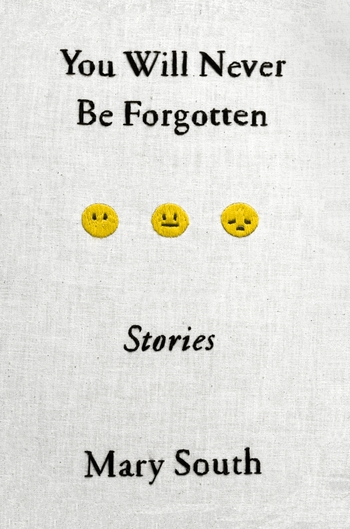

Mary South's "You Will Never Be Forgotten" offers a whole "Black Mirror" season's worth of unsettling future visions

Outrageous, intelligent, and darkly hilarious, You Will Never Be Forgotten includes characters who are harvested for their body parts, cloned, and surveilled, existing in worlds not-too-distant, or perhaps already identical, to our own.

Mary South’s debut collection draws upon the genre of dystopia (think: Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah and TV shows like Black Mirror) in order to defamiliarize received notions about the world we live in—specifically relating to capitalism, technology, and gender—as well as pointing to the absurdity that lies at the heart of many of these accepted beliefs. But don’t be fooled: beneath each of South’s seemingly absurd premises are characters who struggle to move past trauma, all the while grappling with shame, despair, and sadness, in order to heal.

This spring, we spoke about the origin of her stories, the effects of using humor and surrealism in one’s work, and art’s powerful ability to help “deprogram” destructive ways of thinking and existing in today’s troubled times.

Daphne Palasi Andreades: Many of the stories in You Will Never Be Forgotten feature premises that feel wildly imaginative and, yet, not far off from our own reality: for instance, a camp dedicated to rehabilitating teenage cyberbullies in “Camp Jabberwocky for Recovering Internet Trolls,” a mother who “rebirths” a clone of her deceased daughter in “Not Setsuko,” assisted living patients who call sex hotlines in “The Age of Love,” and so on. How did these stories begin for you?

Mary South: I often begin by linking an emotion to a strong image. I got the idea for “Not Setsuko,” for example, by thinking a lot on grief and what it is that finally allows someone who is intensely grieving to move on. It’s actually rather mysterious. How do our minds and our bodies allow us to let go of excruciating pain? At one point, I asked myself the question, “What if someone who is grieving simply refused to move on?” That immediately prompted the image of a mother whose daughter has tragically died, and she just can’t bring herself to feel the loss. She believes it might destroy her. Around that image I was able to build the story of a mother who is trying to exactly duplicate her deceased daughter’s memories for her second daughter so she can live in the illusion that she had never really passed away. Her daughter, Setsuko, has just been “absent” for a while.

Other stories began similarly. “Architecture for Monsters” began from imagining buildings that were designed to not just emulate the human form but to emulate the ruptured or damaged human form. I had so much fun coming up with imaginary designs; that was perhaps the most fun I had while drafting the collection. “Keith Prime” came almost fully realized at once, pairing grief again with late capitalism and a woman doing her best to survive in a job that values people only for how it can profit off them—literally, for their parts. I had this image of rows and rows of identical men sleeping in a warehouse.

DPA: I can’t help but admire the absurdist underpinnings to your work. I was reminded of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, as well as work by contemporary writers like Aimee Bender and Yukiko Motoya, where outrageous events are unquestioningly accepted as “the norm” within the world of their stories. And yet, beneath the absurd premises in your work, are characters who long for connection or are trying to heal from a trauma. Why begin a piece with a seemingly absurd, outlandish, or surreal proposition?

MS: A novel that I love and that’s been incredibly influential for me is Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. “Keith Prime” owes a lot to that novel, in that I wanted to explore another side of Never Let Me Go—the logistical or bureaucratic side and what it’s like for those who are doing the actual harvesting of clones and their body parts. One of the aspects of Ishiguro’s novel that so fascinates me is how, despite its outlandish premise, none of the characters question the validity of their basic reality. They never say, “It’s unfair that we’re raised for parts. We need to completely change the system.” They say, “I wonder if it’s possible for us to get an extended leave of absence before our donations.” We’re all indoctrinated into reality, and in the process of living we have to figure out the ways in which that indoctrination was for our benefit and survival and the ways in which that indoctrination was harmful or for someone else’s benefit. I think life is often a deep deprogramming in this manner. But by starting with an absurd premise that the characters just take for granted as “this is what life is like,” it strikingly reveals this kind of reality indoctrination that we all experience.

We’re all indoctrinated into reality, and we have to figure out the ways in which that indoctrination was for our benefit or for someone else’s.

Starting with an absurd or outlandish premise also allows me to get at genuine feeling more easily. I find “The Age of Love,” for example, to be a deeply sad story; the elderly men dialing phone sex hotlines often say humorously uncomfortable things, but there’s some weird catalyst in the laughter that makes their loneliness more palpable and affecting. My characters are also often unwilling to fully reckon with their trauma, which is what’s required to heal or become a better person. Humor lets them hide for a while but also ultimately exposes their wounds. The neurosurgeon recovering from her husband’s suicide in “Frequently Asked Questions About Your Craniotomy” can often be quite witty, yet that wit won’t soothe her sorrow. Only feeling her sorrow can do that. But I need to show them hiding first, eliding and making light of their pain through jokes, before I can break them open.

DPA: Simultaneously, your collection and its absurdist stories also made me think of events happening in today’s world that are indeed outrageous, but accepted by some as “the norm:” children in cages, the destruction of the earth, our current president who “grabs women by the pussy.” What, in your opinion, is the role of fiction and art in today’s social and political climate, if any?

MS: I was going to say in my last answer that I don’t feel like I have to invent much or stretch the world too far past recognition in my stories—our current reality is often a horrifying dystopia. When a family can lose their house due to an unexpected medical crisis, that is a nightmare reality. My bitterness over the injustice of the state of health care in this country incited me to write “Keith Prime.” And the traumatizing content moderation jobs featured in the title story are also upsettingly real.

It’s difficult—nigh impossible—to measure what effect fiction has on the human psyche, regardless of the studies that have attempted to quantify how it influences our capacity for empathy. And I don’t think anyone would posit that fiction in and of itself is able to mobilize policy change. I do know that art, fiction in particular, has always been what I’ve turned to in order to make sense the world and the people in it. Nowhere else have I found that same kind of deep, almost cellular-level understanding. After I read Mrs. Dalloway for the first time as a teenager in college, I felt I had gleaned something essential and true about life, despite not being able to articulate exactly what that was. I could spend my whole life trying to articulate what is essential and true about Mrs. Dalloway. The same goes for so many books.

Once, I heard therapy described as “releasing into the conscious mind what is unconscious.” The goal—or hope—is that revelation, of habits and traumas both major and minor, will over time fundamentally alter the self. I think fiction is capable of this, too, on both the individual and the collective level.

DPA: An aspect of your work that I found extremely impressive was how you balanced the ostensibly dark subject matter of each story—suicide, rape, and other traumas, as well the despair, loneliness, and grief that the characters feel—with humor. I found myself laughing, and my jaw-dropping: Did Mary just write that!? Humor added levity, while also drawing attention to characters’ very human contradictions and inconsistencies, or the ridiculous worlds that they inhabit. Why use humor in your work?

MS: One of the strange things about devastating emotional pain is that while you’re experiencing the worst of it, you can also, surprisingly, have a completely unrelated thought—even one that is very funny. We all contain multiple voices, internal ways of talking to ourselves, voices that are snarky, tender, resentful, forgiving, etc. It can almost feel like a betrayal to the original feeling if, in the throes of grief, for example, you randomly recall a memory that is really humorous about a lost loved one. But that’s not a betrayal, that’s your mind’s way of letting light in through the darkness of loss, of helping you to heal.

So humor is a great provider of relief, but it’s also revealing of pain, as I mentioned earlier; at some point, you can no longer use humor to mitigate your less-than-pleasant feelings. In that sense, once the laughter subsides, I think it allows me, at least, to see these worlds and these characters even more clearly than I would otherwise—and for the characters to see themselves. It’s also just fun! I think the writer should have fun. If the writing is enjoyable and interesting to you, writer, then chances are it will be enjoyable and interesting to readers.

DPA: If I’m remembering correctly, you mentioned to me once that you don’t begin writing a piece until you have a general idea of the end. This surprised me greatly, perhaps because I work the opposite way: unplanned, blindly feeling my way through. Can you speak more about your writing process; do you have any routines? What was the most challenging part of writing this collection?

The funny thing about writing a book is that you’ll likely become a different person by the time you’ve finished it.

MS: I have worked that way until now—knowing the general arc of a story from beginning to end before starting to write. That process will likely remain the same for me when working on short fiction. There’s a lot of pleasure in just having an idea for a story and developing it, slowly, with no urgency to begin until there’s a sensation of fullness about it. I enjoy taking long meditative walks, outlining, journaling about the plot, characters, themes etc. However, I’ve begun working on a novel as my next project, and I’m not sure I’ll be able to know as much about the overall arc as I do with stories just because there’s so much more information to hold inside one’s mind. I’m doing my best to let it be looser than I’m usually comfortable with, to be more a process of discovery.

The funny thing about writing a book is that you’ll likely become a different person by the time you’ve finished it. As much as I am still proud of all of the stories in my collection, I’m not sure I could sit down and draft some of them anymore. Yet that’s also liberating—who knows what this next book will be like? Or my next after that?

DPA: What writing advice has fueled or challenged you?

MS: There should be no moment in a story where the author is just laying out information. Information should always be filtered through point of view. If it’s really important that we know a character is tall or rich, you have to find a way to communicate that through voice.

In studying with Gordon Lish and working at NOON, I’ve also become preoccupied with the sonic qualities of the sentence. Can I end the sentence with the strongest, most interesting word? And if I’m not doing that, why not? How can I carry an initial set of sounds forward through the prose, from the beginning of the first line to the next and the next after that? Perhaps I want to work in short, staccato sentences. Or perhaps I want to luxuriate in parataxis, to list and digress and embellish coordinating conjunction upon coordinating conjunction.

I also think it’s fun to voice hop—to have a story that’s incredibly ribald and then to switch registers and have one that’s deeply mournful or in denial. Or one that’s a combination of all of those. You can then write in wildly different types of sentences in order to reflect the interior realities of those characters. It’s been absolutely fascinating to learn how to accomplish those turns of consciousness in fiction.