Books & Culture

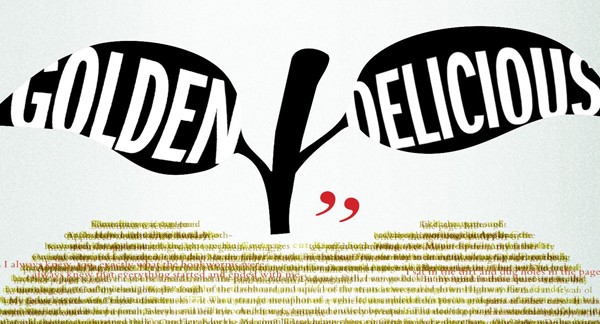

Christopher Boucher’s Golden Delicious Proves That Sentences Make the Best Pets

There’s an episode of Adult Swim’s wildly successful animated romp, Rick and Morty, where the eponymous duo is chased across the multiverse by a gaggle of alternate dimension Ricks. (Don’t ask.) Hopping from ‘verse to ‘verse, a running gag emerges where one world’s inanimate objects are another world’s animate inhabitants. In one, a slice of olive and mushroom pizza calls for takeout: “Yeah, I’d like to order one large person with extra people, please.” His companion, a pepperoni slice, interjects: “White people. Nononono — black people. And Hispanic on half.” After a few iterations, Rick and Morty settle down at a restaurant called La Poltrona Fame (The Hungry Armchair) in a universe where chairs sit on people. They order phones à la clams and phonesgetti with phoneballs.

Christopher Boucher’s Golden Delicious takes a concept similar to this and runs with it for three hundred pages. This is a world where humans date vending machines and traffic cones run society, where houses chat and move and sentences are kept as pets. It’s bonkers, in the best way.

Our hero, _____ (yes, an underline is his name), is a pudgy, bald, and lonely teen whose only close friend is the Reader (that’s you), and he’s the disappointment of his family. His father, Ralph, is a down-on-his-luck landlord, and the only one who takes much of a liking to _____. His quick-tempered mother, Diane, certainly does not, even when she’s around; for the bulk of the book, she’s either off with a group of flying Amazonian-type dictatorial matriarchal warriors called the Mothers, or training to become one of them. _____’s sister, Briana (later the Auctioneer) barely gives him the time of day.

_____ and his family live in Appleseed, Massachussets, a town filled with prosperous apple groves and rich in meaning. And by meaning, Boucher means money. Here, meaning is currency — truths and theories each have their worth. And with that meaning, _____ and his family can buy all sorts of things — like chips, or questions.

The book’s central conceit is that it is, in fact, a book. The earth beneath _____’s feet is not soil, but pages, and his family originally hailed from “the margins.” Language is grown, and sometimes sentient, like _____’s pet sentence, “I am.” Thoughts are sentient, occasionally leaving characters’ heads or influencing their behavior unduly, and prayers are words shot out of the head and sent toward the intended recipient. At one point, _____ leaves the story and heads to another novel. In any other book, this would be a Fourth Wall break, but here, the idea that life is a story is par for the course.

The town is quaint and lovely, in spite of its oddities. Named after the famed Johnny Appleseed, its legendary founder, Appleseed makes due with his Memory, who wanders about planting and harvesting language and ideas. But as the book progresses, it becomes apparent that Appleseed is in crisis. Bookworms begin to appear in the shapes of letters or sentences, digging holes throughout the town and, eventually, even its residents. As the plague grows and things get worse, _____ gets more and more depressed — or maybe it’s the other way around. His mother abandons his family, his sister runs off in the middle of the night to go to auctioneer’s school, and his father, utterly meaningless and in debt to a few imposing banks (which, yes, are sentient), abandons his buildings and goes to work at a factory where work and toil are produced. _____ is left alone with no one but “I am.” and the reader. Then the reader leaves, and the sky darkens.

The beauty of Boucher’s concept is that Golden Delicious can afford to be an utter hodgepodge peppered with nearly inexplicable happenings and still make an elegant sort of sense. Once the reader — uh, that is, the Reader — accepts the book’s internal [il]logic, parsing the wending tendencies of the plot becomes relatively intuitive. And hodgepodge it is: part bildungsroman, part picaresque, and part meta-commentary on reading, living, and meta-commentaries themselves.

It’s in the area of meta-meta-commentary, an admittedly complicated trick, that the book occasionally falters. In one of its rare fumbled moments, the Reader is forced into a position where her presence is required to put the story back on track. It feels a bit like a Breakfast of Champions sort of deus ex machina, as she literally revises the story to end in a manner that satisfies the reader. Or the Reader. Or both?

But isn’t that right, in the end? Don’t we, the readers, fill in the shadow between dead words on the page and the mind in which they spring to life? Is that not, in a sense, revision? Boucher, thankfully, doesn’t say — nor does the Reader. Only the reader can do that. Meaning is, in the end, our true currency.