essays

Dan Mallory Is the Oldest Story in Publishing

The explosive story of a con artist editor lays bare the everyday lies publishing tells itself about who deserves to succeed

This past week has felt like a rough century in book publishing, especially if you’re a woman of color in this traditionally white and monied industry. In many ways, it’s still a 19th-century business, with an overall culture and compensation structure that reflect another era. In the United States, what “19th century” evokes for many white men is a time of even greater freedom, power, and absolute control. For everyone else, it’s a complicated spectrum of misery and struggle. Their nostalgia is for a time when we weren’t considered people.

When people romanticize the Golden Age Of Publishing they are often imagining iconoclastic (difficult) male authors creating art alongside dashing male editors with generous expense accounts and a certain panache. There are a few familiar names that resurface in these conversations — Maxwell Perkins, Gordon Lish, Robert Loomis — always couched as gentlemanly gatekeepers who understood how things were to be done. A 2011 Atlantic profile of Loomis lamented that, on the eve of his retirement, “publishing is not as genteel as it once was.”

When people romanticize the Golden Age Of Publishing they are often imagining iconoclastic male authors creating art alongside dashing male editors.

Genteel — that amorphous, loaded phrase — has often been weaponized as class, race, and gender warfare. And however well-intentioned, “genteel” is doing the work of a cudgel here. To someone in power, it might seem innocuous, a call for “civility” (sound familiar?). To someone trying to break into a power structure it means “you are not good enough, you will never be good enough, and we will never teach you the rules.” It’s not genteel to discuss your salary. It’s not genteel to push back in a meeting on racist or sexist language. It’s not genteel to question the “gaslighting, lying, and manipulation” of your white, male coworker because he fits a received idea of how a superstar book editor ought to look and act.

Readers of Ian Parker’s now-infamous New Yorker profile on liar, con artist, and erstwhile editor and novelist Dan Mallory noted that his coworkers and peers thought of his rise to power as the plot of The Faculty — a film in which an alien parasite infects all the teachers at a school, and no one believes the increasingly terrified, endangered students. His bosses, mentors, and decision-makers all profess, well, genteel shock and “astonishment” when confronted with his embarrassingly inept lies. “How could we have known this man, who told us he wrote a thesis on Patricia Highsmith, carries on about The Talented Mr. Ripley endlessly, and who has been filmed lovingly holding the book up to his chest while talking about his own novel was, in fact, Ripley?”

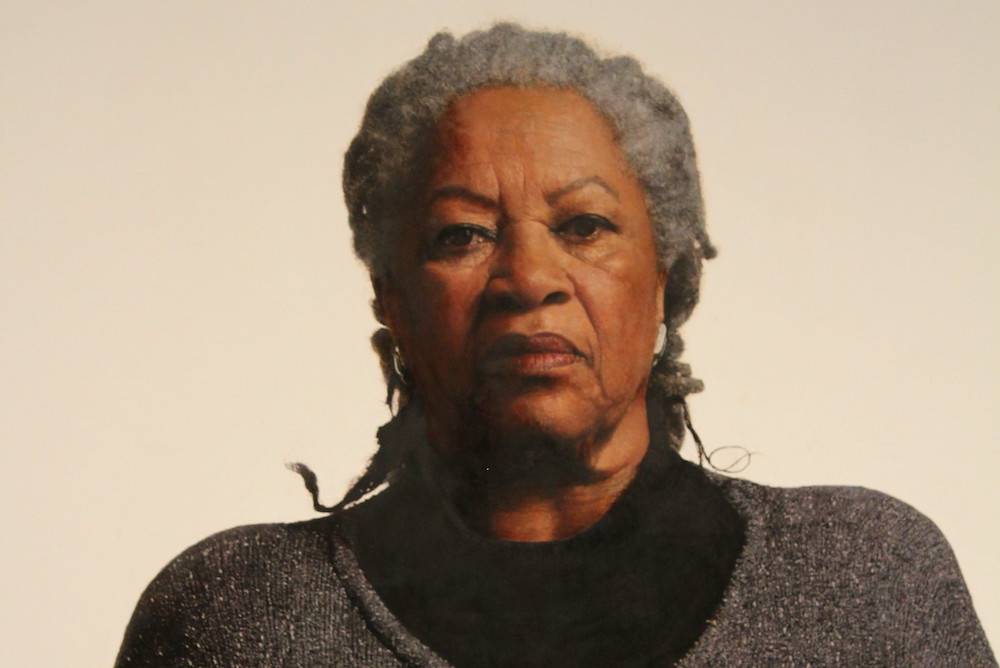

The lack of scrutiny is even more jarring when you think about Toni Morrison’s decorated career as an editor, how her publisher wanted to send cops along with the publicist to a Harlem launch party she organized, how hard she fought to acquire the books she championed, how even when she’d written and published The Bluest Eye, she at first didn’t tell anyone at her job she wrote at all. (Toni Morrison!) Meanwhile, the publishing world’s Dan Mallorys blithely accept multi-million-dollar deals as their due.

You can look at the damning stats and the story becomes clear in this overwhelmingly white and middle-to-upper-class industry. The kids who spot the alien parasite, who see through the story, are probably overworked and underpaid and far more likely to be from marginalized backgrounds, and the hoodwinked or willfully apathetic people in charge are likely to be white with real estate in multiple states. In 2017, when the Weinstein allegations broke, Lindy West wrote in the New York Times that “to some men — and you can call me a hysteric but I am done mincing words on this — there is no injustice quite so unnaturally, viscerally grotesque as a white man being fired.”

Far from being fired, this white man, with his fake brotherly “e.mails” and fake cancer and fake family deaths, seems like he’ll be fine. He’s already made millions with his book deal and film options, a book that openly, vampirically depends on the work of the female authors who preceded him. The movie adaptation has A-list stars. He’s thinking about a TV show. He has a half million dollar apartment in Chelsea and a cute dog.

Both the Mallory New Yorker profile and the recent documentaries about the Fyre Festival, a widely covered social-media-driven grift perpetrated by Billy McFarland, have this double vision. We see white man after white man extolling how “charismatic” and “magnetic” McFarland is — and then we’re treated to a perfectly average guy parading across the screen, while one of his former employees, a woman of color, drips disdain and recounts with clenched teeth how the writing had been on the wall for months before everything came crashing down. At Mallory’s very first editorial assistant job, where he thought the fiction was too downmarket and the job too administrative, a male coworker recalls him as “a good guy, lovely to talk to, very informed.” Mallory allegedly spent his evenings at this job urinating in cups at his female boss’s desk.

It’s the romance of playing a game that you will always win.

An industry professional in the New Yorker profile calls publishing “a business based on hope.” It’s performative by nature. A friend in the industry has deadpanned that “we’re all just LARP-ing,” roleplaying as publishing professionals based on some (nineteenth-century!) idea of what that should be. Very few people have chosen this path because of the money. The romance is the occasional genuine feeling of “they pay me to do this?” and the potential that you might be shaping a public conversation. That magical thinking also opens up ways for vulnerable people to be crushed by failing to perform the correct role. In 2016, one of the industry’s few senior-level black editors, Chris Jackson, asked why he’d gone into publishing, told Publishers Weekly, “I believed in the power of books to shape the culture.” In that same article, a Big Five HR executive, when faced with the notion that race or class might affect hiring, complained, “It’s not about socioeconomics. It’s as if it doesn’t count if we hire someone black who went to Skidmore.”

For a woman of color, the hope that keeps you going is the hope that you’re helping create a book for a younger version of yourself, one who contented herself with work in which it never occurred to the authors that someone like her might have interiority or agency. For a man like Mallory, the romance is this fantasy of a bygone era, when gentlemen were gentlemen, and the idea of talking about inclusivity in literature was absurd. It’s not the romance of having the power to redress deep wounds that have made who you are who are as a reader and editor. It’s the romance of playing a game that you will always win.

We work in a system always aware of the next door that might close in our faces. Men like Mallory work in a world where the shallow, regressive role-playing he engaged in was the strategic move. There is something especially insidious about the way that he needed to be both the golden boy and the tragic hero, beset by unlikely gothic calamity. He wanted to be the abused underdog as much as the prince in waiting, and the system — built from centuries of received notions and power structures — tripped over itself in its haste to reward him.

It always gave him the benefit of the doubt, no matter how comically outlandish and incompetent his lies became. For the company that gave him ten times the salary of the assistants who were probably doing his work while he disappeared from the office for months at a time, all he needed was his readymade narrative and identity. For that genteelly “astonished” former professor, he represents a future and a legacy in a way a woman of color would not. To those in power, he’s a plausible mirror and heir who reifies their position and continued relevance. It is impossible to shatter this kind of entrenched privilege with objective truth. Mallory’s transparent humble bragging was “modesty.” His evasiveness about the truth was just his sense of forbearance. His inability to do the work was just proof that he had managed to claw his way to the top despite difficult circumstances. People ask: how did he get away with it? In this deliberately closed world full of smart people who know how to do research? It’s a simple answer. He fit the part.

People ask: how did he get away with it? It’s a simple answer. He fit the part.

If the industry seems shaken, it’s because we understand that this story was not a one off or even a true surprise when you drill down. Many of us have worked with a Dan Mallory type, have watched someone rocket up the hierarchy without doing the work. It’s because there are many, many women, especially women of color, sitting in their cubicles (there are far more men with doors that close) reading about how this man lied his way from assistant to executive editor in a few short years while no one even questioned him. The industry culture is designed to buy into that con, that destructive, specious fantasy of elegant men from a more “civilized” age. It’s embedded deeply, a cancer more real than anything Dan Mallory had.

Many people of color in this industry make gallows jokes that it can sometimes feel like we’re all in Jordan Peele’s Sunken Place. Dan Mallory might be a thriller novelist, but his own narrative is a slow-brewing horror movie. Like the profile says, “the call was coming from inside the house.” At an event earlier this month for The People’s Future of the United States, author Alice Sola Kim described the experience of reading horror as a woman of color as “there’d be this thing that was after you, made for you somehow; it wants you, specifically, which is part of the awfulness of it — like a lock and key. And I feel like that’s applicable to life in the sense that there are all these horrors that depending on who you are, or what group you belong to, there are people, institutions, ideas, that are after you…. And you don’t always survive — you often don’t — but sometimes you do.”

For marginalized people trying to shift the industry, the Dan Mallorys are a lock and key made for us, to horrify and to mock, to tell us what we already suspect in low moments — we are not genteel or white or good enough. The details read like a bad parody of what we always knew, that someone like him could cheat and lie — badly even — and still have a shot to rise to the top at astronomical speed. Your victory of an inch feels meaningless in the face of this operatic marathon of a career con.

I’m lucky to be in a place right now where I’m valued and supported, empowered to amplify creators of color and to remove barriers where I’m able, but I exist within a larger industry with this checkered history. It is difficult to explain to someone who has never experienced it the specific anxiety of walking into a meeting and being the only one, and equally difficult to explain the sheer power of just seeing a marginalized face in a senior role, to see the hint of a track. I owe a deep debt to the editors of color who came before me, who endured and broke new paths for people to follow.

In a 2018 Publishers Weekly feature on black publishing professionals, Nicole Counts at One World (headed up by Chris Jackson) says that as a fellow person of color, her boss “intuitively understands — or, in cases where he doesn’t, does the work to learn — constantly reminds you that you are allowed to take up space, you are allowed to feel these heavy feelings, you are allowed to need a break.” This trust, this ability to imagine a future with yourself in it, is powerful and fundamental to what this industry will look like for the next generation.

Being a person of color or an ally in book publishing means fighting a battle against the past.

Being a person of color or an ally in book publishing means fighting a battle against the past. Mallory is a reminder that the past isn’t even the past. It’s a living ghost that will throw everything you’ve fought for in your face. The story, as absurd and entertaining as it was, was also sobering, because it felt like an embodiment of everything we hoped our industry has moved beyond. Mallory didn’t just perpetrate a con on publishing — he proved that the prevailing culture of publishing is the con. That the work that’s been done and that we still have to do is backbreaking and tremendous.

There’s no closure, because we know he’ll be fine, the monster that’ll get away. Some of us — exhausted by the constant emotional labor, the draining experience of being the only person who looks like you in room after room, the financial strain — get out and are better for it. And our only other option? Create our own networks. Identify the monsters. Survive. Use what power you have to lift up marginalized voices and change the landscape, inch by inch. That’s why we’re here.