brooklyn letters

How the Brooklyn Literary Scene Is Striving to Be More Inclusive

An oral history of the struggle to make space for women writers and writers of color in Brooklyn

The Brooklyn Letters project is a series of oral histories of literary Brooklyn from 1999 to 2009, presented by Electric Literature with support from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

This is the final installment of Brooklyn Letters. You can read earlier oral histories here.

Publishing still isn’t an equal-opportunity space for people who aren’t white men — but at least we’re talking about it now. It’s hard to remember how limited and lonely the world felt before we reached our current level of cultural awareness of racial, gender, and sexual discrimination — when our discomfort with an all-white male literary panel might go completely unregistered, because outside of private conversations there wasn’t even a place to register it.

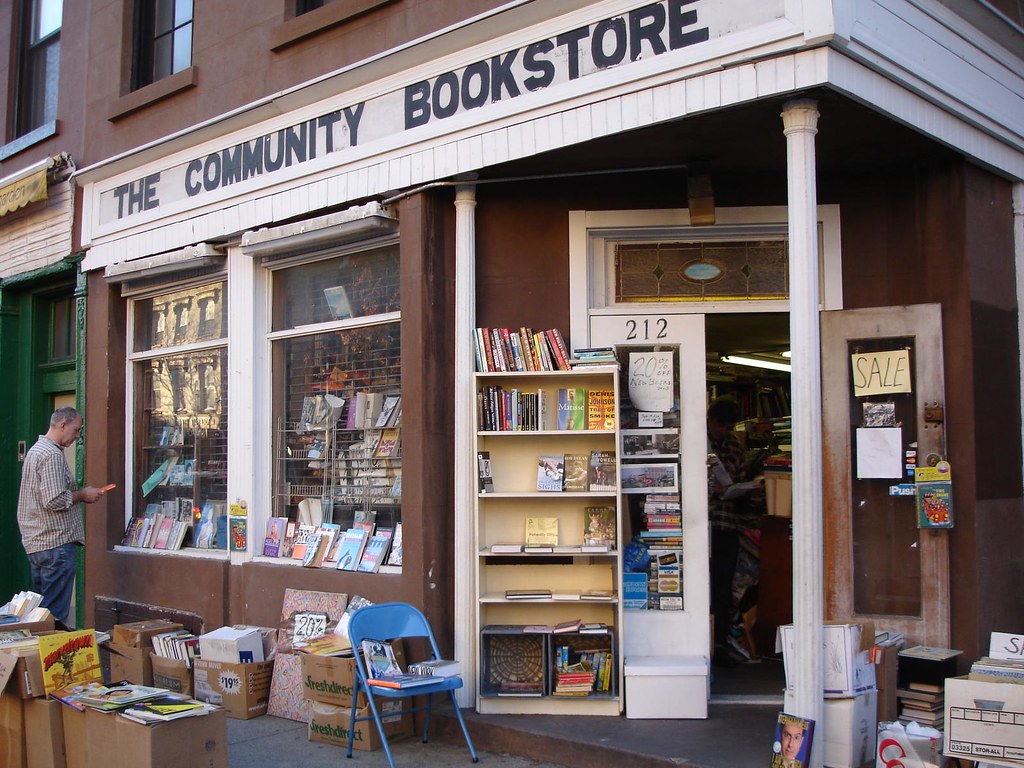

At the beginning of Brooklyn’s ascendancy as a literary place — with its rising concentration of writers, editors, publishers, and agents moving from all over to this one borough, and often even to just a handful of neighborhoods within the one borough — there was no guarantee that you would find the space, the reading series, the magazine, the press, the publisher here that represented you, where the work being featured might actually speak to you. And while these blind spots in the literary scene weren’t unique to Brooklyn, they were certainly represented here, and reinforced as well by the mainstream publishing industry that was based in Manhattan, a short subway ride away across the East River.

There was no guarantee that you would find the space, the reading series, the magazine, the press, the publisher here that represented you.

An entire decade later in 2010, when VIDA — a non-profit organization that gives an annual account of the number of men and women reviewed by or published in major literary magazines — released its first full report, the results showed a staggering gender imbalance across the publishing industry, numbers that on the whole haven’t greatly improved in the near-decade since. And yet, at the local level in Brooklyn between ’99 and 2010, change did come — slowly, painstakingly, and because of the action of individuals within the borough’s literary community. In this oral history we’re going to hear from some of those figures — curators, publishers, writers, and literary citizens — responsible for addressing the lack in Brooklyn’s literary scene, as they talk about what changed, how it happened, and what it meant.

Mira Jacob [author and co-founder, with Alison Hart, of Pete’s Reading Series in Williamsburg; with Hart she ran the series out of Pete’s Candy Store bar, directly below the apartment they shared after they met at The New School MFA program, from Fall 2000 until 2013. The series continues to run, with another set of curators, today]: One of the first problems that walked into our lives was that it was really hard to find women to come and read. The imbalance was something that became clear to us pretty much right away. Men would recommend each other, and men who were not qualified would recommend other men who were not qualified. It was amazing. They would be like, I clearly should be here, and my friends should also be here. Meanwhile women who were overqualified, who were incredible, would get there and be nervous, as if they weren’t allowed to have that space. And maybe for that reason they also wouldn’t recommend other women.

When we first started there were a lot of stories written by rock-and-roll white guys in which nothing would happen. There was one guy in particular, a very established male author, who would read forty minutes of just setting — just scene description. We always told our authors, fifteen minutes, twenty minutes tops. I was pretty aggro about it: “Do not read for more than twenty minutes. It’s not fair to you, or the other authors, or to your audience. Don’t ever do it.” We had this guy on three times, and every single time it was the same situation. Like: “You are all here for me, and I will hold you captive for forty-five minutes, because I’m just going to keep reading. It’ll be long past the point of you wanting to hear, but I have zero register for that.” Meanwhile, a woman would get up there, and at minute five she’d say, “I’m just gonna stop. I’m just gonna stop now.”

It would never cease to amaze me what certain male writers assumed was important for everybody. You just read a long rant against your ex-girlfriend, and subjected this entire bar to it? And somehow you felt entitled to do that? From the beginning there was clearly a disparity in terms of who felt entitled to talk.

Rob Spillman [co-founder of Tin House magazine; since 1999 Spillman has operated the bicoastal literary magazine in Gowanus with his wife, author and co-founder Elissa Schappell]: Prior to starting Tin House my wife had been the senior editor at The Paris Review, and both of us had always chafed against the very maleness of that publication, especially the white maleness of it. Having grown up in the queer world of Berlin, which was very multi-culti and obviously very queer, my sensibility was more playful and fun. So we felt from the beginning that we didn’t want to publish the same voices that everybody else was publishing. We wanted new voices, and women in particular.

Nowadays with the internet it’s much easier to have conversations about things like gender diversity. It’s affected how quickly we react to things, and how quickly we find out about them. When the first VIDA Count came out [a non-profit founded in 2009 which releases yearly reports on the number of men and women reviewed by or published in major literary magazines], we found some really interesting things in there. For instance, that two-thirds of agents are female, but that two-thirds of what they were submitting to publishers was by men. Which either means that men were giving them more things to send out, or that the agents themselves were choosing to send out more things by men than by women.

When I looked at our own numbers, in terms of gender Tin House’s slush pile [the unsolicited work being sent to the publication] was 50/50. But when I sent out encouraging rejection letters — like, “This isn’t going to work for the magazine, but please feel free to send me something else” — as opposed to flat-out no’s, women were four times less likely to send something again. It seemed as if their reaction was, “Oh, you’re just being nice.” Whereas when I sent out encouraging rejections to men, they would immediately say, “Here are five more things. Here’s my desk drawer.” They would just take it literally.

Anecdotally I see that at places like AWP [the annual Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference]. Late night at a bar some guy will write down something on a napkin and say, “Hey dude, what about this pitch?” Whereas my wife would never send something out unless it was completely polished and had been thoroughly vetted — until it was just absolutely airtight. And all of her friends are that way, too. With a sense that they’re not entitled, versus the men who will just send me the sloppiest shit possible. I see that in the submissions and I see it in who takes up the air at readings, where you have to be explicit about the fact that no, eight minutes means eight minutes. I also see it in who actually volunteers to read. Whenever we plan a book launch event, men will be like “Oh yeah. Pick me, pick me.” Whereas, generally speaking, the response by women is, “Oh, only if you have space.”

Jacob: I feel like people have an amnesia about what it was like at that time to be a creative person if you were a woman. In the revision of history it’s like, everybody was pushing each other forward, all the time. But no. Everyone was scared. Everyone felt unwelcome and tentative and very tender. It came out of two things, I think: one was the feeling that we were not allowed in that space. And the other was this sense that, at most, there could only be one of us there at a time — that that was as much as the space would hold. If you were a woman, and a woman of color, yes of course you wanted to lift up other women of color, but only one of us got to occupy that space. You felt so barely welcome yourself that if you did recommend another woman, it was only with great trepidation. And so, starting a reading in a space that had for so long been dominated by the white literary men of New York, we were not only aware of this problem but it was something we came up against right away. Quietly to each other we said, “We’re going to make space for the women and the people of color.” But in reality it wasn’t so easy. It was a process of anguish between us, and it took an incredible amount of digging.

Spillman: When we did that first deep dive into our VIDA Count, Tin House’s numbers were better than everybody else. We were 60/40 [60% men published to 40% women]. And we were actually surprised, because we all assumed we had gender parity in what we were publishing. Everybody on staff, we figured, “Oh yeah, we walk the walk.” And it turned out we were only 60/40 — and yet somehow that was still the best.

The immediate thought for us was, “Wait, how did this happen?” We looked at our own internal numbers, and saw that we were reacting to what we’d been getting. From agents we were getting two-thirds men, and from those who were resubmitting we were also getting mostly men. But at that point we hadn’t realized this was even happening, because we all thought we were picking a lot of women.

There were other more subtle things, too. In our Lost & Found section, where we have people write about underappreciated books and authors that should get more play, my editor in charge of that had been really good about having gender parity in the folks writing them. It was 50/50, perfectly, even back then. But when we took a look back, we saw that despite the parity the subjects were still 70% male. So it meant that both women and men were choosing to write about men. We’d been giving out prompts like, “Write about a favorite underappreciated Booker Prize winner.” And women were mostly picking men.

Of course, part of the reason for that is historical, because men have traditionally been more published by the industry. But it was still a misstep on our part. We had been blind to that. We thought, “Look, we’re publishing all these women!” And so it gave us a chance for a real corrective. In the Lost & Found pieces we started tweaking our prompts to specifically ask if there were any women the writers might want to highlight. And I also tend not to solicit men, honestly because they take care of themselves, and I’ll redouble my efforts with women whose writing I like. I’m careful now in my rejections to say, “No, no, really. Please do send me something else, this one just didn’t fit in the issue. I really do want to see your stuff.” Ultimately, it’s just a matter of paying attention.

I tend not to solicit men, honestly because they take care of themselves.

Jacob: When we started the series we had to see how it was going for a bit before we realized that we would actively have to make sure there were enough women in the season, or that there was diversity. It wasn’t baked in. These days that’s just part of the conversation. It’s like, what the hell’s wrong with you if you aren’t doing that? But at the time we had figure our way through it, while feeling crazy that this was even something we were struggling with.

One of the challenges was that, in the absence of social media and the internet in general, people just did not self-promote in the way they do now, which is unapologetically. Nowadays it’s pretty accepted: writers get out there and they’ll say, “This is me, this is the thing I’m doing.” But back then you never would have done that. It was considered tasteless, which of course meant you were so much more reliant on the publishing industry to forward you, and the industry was mostly only favoring one kind of person.

The way we finally got around it was by going through the publishing catalogs ourselves. Every so often you’d get a catalog, from MacMillan or one of the other publishers, of the books they had coming out that season, and we’d just go through them and choose the people who weren’t already front and center, and then reach out to them. Suddenly we had a different way to crack it. Instead of relying on agents and publishers, we started taking direct control of their lists.

Alison Hart [co-founder of Pete’s Reading Series]: But sometimes it also just took us pushing on them a little. If the agents or publishers recommended people, we would follow up and say, “Any women?” Because often they weren’t even aware they were doing it. It would turn things around on them a little bit to think, “Oh.”

Jacob: I also remember us having strategic conversations about who to ask to find women. How do we find this community of people that almost don’t have a community themselves — that are so scattered they don’t even have a way to talk to each other? Who do we approach? Who’s a connector? What editors do we know that are actively publishing women?

Joanna Yas was a great resource, and an extraordinarily generous person. She was the Managing Editor of Open City at the time [a magazine and publisher founded in New York in 1990, and which published its last issue in 2010].

How do we find this community of people that are so scattered they don’t even have a way to talk to each other?

Hart: She knew and was friends with a lot of writers, and she didn’t guard her insider knowledge.

Jacob: I remember saying to her multiple times that it was impossible to find women, and she would just turn around and say, “Here are five names, try these five people.” And they were always amazing.

Unfortunately the same difficulty we had in the beginning with finding women happened a couple seasons later with people of color. I remember being like, “Where are the people of color?” But nobody could help with that. Nobody at the time had a good list for that.

Spillman: One of Tin House’s early contributing editors was the poet Agha Shahid Ali, who was also a translator, and he was very persuasive. He would come to me and say, “This is the best Farsi language poet of all time, and you’re going to publish him.” So okay, let’s do it! I would trust him. More recently, when our poetry editor was leaving, we specifically went out and hired a woman of color [the poet Camille T. Dungy]. Because how else are you supposed to address the whiteness of the industry? It’s a systemic problem.

Alexander Chee [author of How to Write an Autobiographical Novel and The Queen of the Night]: The whole reason Edinburgh [Chee’s debut novel, which had been out on submission with publishers for two years] was eventually published was because the Asian American Writers Workshop had a panel on Asian-American masculinity, and I met my editor, Chuck Kim, on the panel. I’d basically given up on trying to sell the book, and he was like, “I’m looking for Asian American literature, would love to read your novel if you have one.” We had just hit it off on the panel and I was like, “Yeah, sure, whatever.” But he kept pursuing me, so I agreed to meet him for lunch. I brought one of the copies of the manuscript I’d picked up from my agent’s office, after she and I had parted ways because she wanted me to work on The Queen of the Night [Chee’s eventual follow-up novel] and try to sell that first, and I was like, “No, white lady, I’m not going to do that.” I understood why people thought what they thought, but I just didn’t want to do it that way. Was I wrong? I’ll never know. But I’m here, so.

Eugene Lim [author of Dear Cyborgs and co-founder of Ellipsis Press]: I co-founded Ellipsis Press with Johannah Rodgers in 2008, largely for selfish reasons: to publish my first novel [Fog & Car] and to publish other experimental fiction works that I loved. I’m very proud of what we’ve published, but I do consider it to have failed in two principal ways. Firstly, I wish I could have gotten more attention for these excellent writers. Evelyn Hampton, Karen An-hwei Lee, Stephen-Paul Martin, Joanna Ruocco — to name just a few examples — are truly amazing writers. As well, though I’ve tried from early on (and will continue to try) to solicit and attract underrepresented writers, I recognize that the press largely replicates the lack of diversity of commercial houses.

During the years we’re talking about, at parties or readings or at places like AWP (which a bitter, cynical writer, who may or may not be every writer I know, told me stands for Average White Poets), because of the dearth of other Asian-American writers I was repeatedly misidentified as Tao Lin, or Linh Dinh, or Phong Bui. As a Korean-American writer who was born here I certainly have and had many privileges, which no doubt helped me find and participate in the nascent scene. And the internet definitely helped connect innovative, “experimental,” and non-commercial writers. But I found, especially in those early years, that hubs and digital gathering spots for writers who identified as both “experimental” and POC was a Venn diagram that largely remained empty.

There is one exception to this. The Asian American Writers Workshop was and is an important venue. I think it has (as I have) also evolved as the Asian American community has evolved (with the single dominant force of change being the Immigration Act of 1965, and its rippling effects through generations of the AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] community). I remember visiting the AAWW early on at its East Village location maybe in the late 90s, and not entirely feeling like I belonged, whereas now I think it fights hard at inclusivity and to constantly interrogate and widen, or at least complicate, the notion of what it means to be Asian American.

Chee: Starting in 1996, the writing community I was participating in in New York was mostly around the Asian American Writers Workshop. In 1996 I got an email from Quang Bao and Hanya Yanagihara inviting me to basically come and hang out with them. They had read an essay of mine in Boys Like Us [an anthology of gay writers telling their coming out stories], and they wanted to meet me. At the time they were both very involved in AAWW. I hit it off with them immediately, and started coming in for the open mic nights. I read at an open mic in the East Village location, I remember, and my agent Jin Auh had just joined Wylie [literary agency] at the time, and she gave me her card there. I had an agent, so I didn’t call her for a few years, but I got her card that night. It just felt very cozy, but also exciting.

One of the most valuable things for me about AAWW was being able to talk about issues of who we write for. Are we writing to each other, or are we writing to this white audience? We had an expression back then for book covers that would be covered in Asian motifs, like fans and chopsticks. It was called “chinking it up.” The author Monique Truong, when she was putting out her book, had told her publisher, “no chopsticks, no waiter coats, no bowls.” And she ended up with a cover that had a waiter carrying chopsticks and bowls — for The Book of Salt, which is set in Paris, and is about this person who cooks for Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein!

The other literary center of community for me happened around A Different Light books, the LGBT bookstore where I worked. Even after I stopped working there I was still very close to them, still very involved. The editor Patrick Merla found me through Edmund White, and was responsible for publishing that anthology, Boys Like Us. There was also an anthology that Hanya and Quang Bao put together of LGBT Asian American writers called Take Out: Queer Writing From Asian Pacific America, that I think was really important and had a big impact in terms of the community-building that was happening at the time.

There were other things I would go to, but I always felt a little out of place because they were really white. But I suppose I also sort of accepted that about them, as part of the story of what they were — as part of “what the deal was”. In the same way that when I went to Iowa [the Iowa Writers’ Workshop MFA program] from 1992 to ’94, it was predominantly white. It just seemed like that’s how things were going to be for a while.

It’s hard, though, to feel like you’re standing there in the group and participating, and also like there’s some screen that makes you invisible, even though you’re right there in the same rooms. That was part of what I felt like I was reacting to at the time. I remember when it was so hard to get Edinburgh published. The submission took two years. I had friends who were like, “We don’t understand why nothing’s happening for your book?” In the editorial feedback letters, I got everything from “Sort of like Graham Swift, but not as talented,” to one editor who just wrote, “I’m not ready for this.”

It was hard because I remember my father had brought me up to always act like racism wasn’t happening, to just keep working and work through it. That was how his immigrant generation dealt with it. To say, “Just ignore it. Is that rain?” but it was somebody spitting at you. Approaching it that way, you don’t get to acknowledge why it’s impacting you, because if you were to acknowledge why, all of that anger would just explode. As I was working on these recent essays [for his collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel], I realized that in my writing I was sometimes performing that same reflex of “What racism? What are you talking about?” And I thought, no, you have to actually talk about the shit that you dealt with, and how you dealt with it, to honestly speak to this new generation — but also to honestly record what you lived through. You can’t just perform your father’s dance.

Jacob: Between the two of us we would talk about it a lot: What aren’t we seeing? We made the effort to find the things we weren’t seeing, but that we knew were around — that there should be a place for. Once we started putting more women on the stage, I felt a change psychologically. And I definitely felt a collective change in the idea of what we could expect for ourselves. I remember seeing women up on that stage and being like, “Right, we should be able to expect this.”

It was amazing too because the series itself grew pretty quickly after that, from this little tiny thing to a point where the bar would be halfway backed up, and they would have to put the reading over the bar’s PA because so many people had flooded in.

We made the effort to find the things we weren’t seeing, but that we knew were around — that there should be a place for.

Hart: I remember when Jennifer Egan read.

Jacob: That was amazing!

Hart: It was Emma Straub’s book launch, and I think they were friendly. Jennifer did not want us to promote her part of the reading at all. She just wanted to go first for Emma; whatever she could do to be out of the way, and let Emma have her night. But so many people came because it was not that long after A Visit From the Goon Squad [Egan’s Pulitzer Prize-winning fourth book] was published.

When it’s a really big night, you open up the door from the reading space and pipe the sound out through the whole bar. That night the entire bar was listening. When she started you could see people’s heads pop up at certain points, like, “Oh, she’s reading my favorite story!” Because everybody had a different favorite from that book. Sometimes when you have the doors open to the bar you have to worry about the noise, but that night nobody in the place said a word. It was like nobody was there to have a drink, only to listen.

Jacob: Even the bartender, Dave, was super quiet about setting the glasses down, because he didn’t want to break the spell.

Hart: As you go along running a series you realize that what all writers want is a place where they can get the words out of their head and into other people’s ears, where you’ve been alone all day and you just need to read to somebody, anybody. To be seen and be part of that shared experience.

Jacob: When I heard people read I would feel like, I too need to make this. I remember just hearing certain stories where it would blow my world apart, and my idea of what I could do, and that I even had a right to do it. It really was a constant self-discovery.

From the beginning, I wanted to make a night for all of us. The people who were doing this work. Not the publishers, not the agents. No matter how much of a pain in the ass it had been to try to get things going, at the end of every night people would come up to us and be so grateful. They would just collapse and say, “This was so good. This meant so much to me.” Because they needed it. Being able to put that out in the world felt like giving people food.

Brooklyn Letters is supported by a grant from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.