Craft

Dearest Jenny: Reading My Chinese Father’s English Letters

You are the one who appears drifting away from us

I’ve been reading my father’s letters. When I find a sentence I like, I write it at the top of the page. Then I wait and see what happens. To me. To the sentence. His first language was Mandarin. In theory, he wrote the letters in English so that I could understand them. Sometimes a sentence that doesn’t make sense in his letter makes sense by itself. The above sentence, in its original context, was missing the words “to be.” He meant to say, “You are the one who appears [to be] drifting away from us.” Read in context, it’s grammatically incorrect. For years, I read it as an error. Strangely, in isolation, the sentence makes perfect sense; it’s beautiful. Such sentences are the opposite of immigrants; they make more sense outside their native context. They make sense as islands unto themselves.

Such sentences are the opposite of immigrants; they make more sense outside their native context.

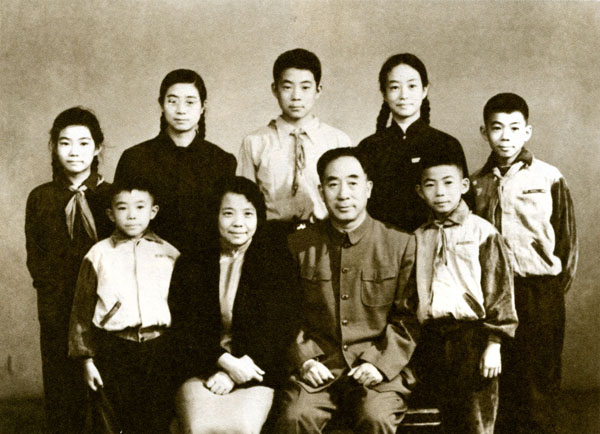

My Chinese father was a stowaway who stole onto a mainland ship bound for the island of Formosa, “the beautiful island,” now known as Taiwan. He left Formosa on an ocean liner to land on another island (New York City), then caught a train to Chicago, married a German American yáng guǐzi, and bought her a Volkswagen Squareback. With their pre-nuptial correspondence packed in the trunk, they drove west through states where anti-miscegenation laws had been repealed and states where they had just been overturned. He wrote his mother letters along the way. Each one began, like a Christian wedding, Dearly Beloved Mother, and was followed by a Chinese body of text. Later he would tell us she was the only person he missed, the only person in China he cared about. Not one of his many siblings, not one colleague or friend, no one else — only his mother. (His father was dead by the time we were born.) My father cared about his mother and yet he kept going. He kept drifting away from her. He covered blue aerogrammes with foreign stamps and handed them to hotel clerks whom he trusted to mail them.

When he arrived with his new wife in California, he wanted a view of the sea, an orange tree, and a lineage. These were his California dreams. The orange tree soon materialized, there was one in the backyard of their ranch style house. There were no seeds in the fruit, nothing to spit out. He hadn’t even known such an orange existed. It was a dream that surpassed his expectations; the dream of eating something whole without regret. The sea was nearby, he could sense it. It was enough for him to know the sea was there. Every Fourth of July, we watched fireworks explode over the waves. He learned to perform intercourse from a book. If it weren’t for the library, my sister and I might never have been born. Further evidence of a red thread tied around the ankles of letters and lineage. Mornings he drifted up the hill on his bicycle to the University. Through the living room window, we watched him. After he moved beyond the window’s frame, we could see him pedaling in our mind’s eye. We knew what the hill looked like. We knew where he was going.

He learned to perform intercourse from a book. If it weren’t for the library, my sister and I might never have been born.

One day our father drove to Texas & stayed there for a year. He wrote us letters on tiny slips of paper telling us what to do, telling us to listen to our mother, telling us we couldn’t have a puppy. On several occasions, he flew to China to give lectures, to visit relatives who were stunned by the news of our existence. He visited his mother. He wanted to bring her oranges but fresh fruit was a prohibited item. He brought her pictures he had taken of us running from the sea in our dresses. He sent us postcards of Chinese monuments written in English. One December, he bought his American colleagues gifts — squat wooden dolls with bobble-heads, hand-painted fans, jade fish strung on pieces of red string — which he allowed us to wrap and place on the television next to a little white tree. Christmas morning, we were allowed to open the gifts, on the condition that we rewrap them for his colleagues afterwards. It was the most exciting Christmas we’d ever had.

When I was old enough, I spent a holiday on Bainbridge Island with a friend’s family. They were the sort of people who brought a pine tree into their home on Christmas, who opened presents they kept for themselves. We dug quahogs and picked blackberries and lay on a dock in the dark striking matches. We did whatever we felt like doing. After I left home, I spent a winter on Whidby Island and a summer on the same “beautiful island” my father had lived on. On my father’s island, in Taipei, people asked me for directions wherever I went. I could hardly understand what they were saying, much less direct them. What they saw when they saw me was my father. My mother was invisible. I was like a sentence from one of my father’s letters. Eventually, I settled on another island, one I had never heard of. Some parents leave footprints in the sand for us to follow, some leave a trail of breadcrumbs in a forest; my father left his signature on the sea.

Just as he knew a language before English, our father had a life before us. Before he was a professor of electronic engineering in California, he was a district court judge in Taiwan. (For our father, and by extension for us, the word “sentence” had a punishing ring to it.) Before that, he was a boxer and a ballroom dance teacher in China. Frequently, without intending to invoke miscegenation, he responded to one thing or another, “I have mixed feelings about this.” Most of the years we lived together in the ranch style house, he spent behind the locked door of his study. Both aloud and in his letters, he was fond of quoting Donne, “No man is an island,” though he preferred solitude to the company of others. Perhaps his mother was an exception to this. His Dearly Beloved. She died before he could bring her to us, before we could travel to meet her.

What they saw when they saw me was my father. My mother was invisible. I was like a sentence from one of my father’s letters.

His marriage to our mother ended; we were twelve and fourteen. He received a multitude of letters from women, in the U.S. and Asia, asking to be his wife. Each one boldly described herself to him, each one pleaded her case. All the letter writers enclosed pictures of themselves that he arranged in rows on the dining room table for my sister and me to appraise. He asked us to rate the women on a scale of one to ten. We were to assign one score for “mother” and one score for “wife.” He asked us to rate the women based on their photographs. I’ll write that sentence again. He asked us to rate the women based on their photographs. He married the one we had given the highest overall rating and in the end they moved back to China.

I have a box of letters he wrote to me, to many addresses, throughout my lifetime. There were times I didn’t open his letters for months. A single letter had the power to derail me. Now it moves me to see the many addresses he persisted in writing, to see the addresses for Cottages at Hedgebrook, The MacDowell Colony, the Fine Arts Work Center, in his ballpoint pen handwriting. I cared about him and yet I kept going. I kept drifting away from him. He followed me everywhere with his letters. Everywhere I went, I wrote him letters. Everywhere I went, I wrote about him.

When I was living on Whidby Island, he sent me a card of a shepherdess standing on a cliff, looking out at the sea. He wrote directly on the painting:

I thought she is just like you.

All by herself on an island.

But on second thought (notice the sheep there).

She isn’t lonely after all.

The last island I lived on was Martha’s Vineyard. Sheep grazed behind stone walls there much like the ones in the painting. I was just like the shepherdess. Except I was lonely. I noticed the sheep but they didn’t cure my loneliness. Sheep were a poor substitute for a father. My first year with the sheep was the last year my father ever wrote to me. The ceasing of his letters surprised me. Whether I opened them or not, I had come to expect them. Though I’d kept them with me, I didn’t remember the shepherdess or his two thoughts until I had moved off island. Forgetting is reflexive for those of us afraid to remember. Our father wasn’t afraid of anything but poverty and death and losing us. He never lived in poverty. His sentences are what I have left. Those beautiful islands that don’t quite make sense in proximity. It’s been thirty years since he wrote me the first letter. Every day I drift toward it.