Books & Culture

Death and Starlight in Chile’s Atacama Desert

Debut novelist Hannah Lillith Assadi on the documentary ‘Nostalgia for the Light’

Patricio Guzmán’s documentary Nostalgia for the Light (2010) paints a stunning portrait of Chile’s Atacama Desert — from its otherworldly, international preeminence as a site for beholding the stars, to the scarred traces still present in the arid land of horrific acts committed under the Pinochet dictatorship.

The film opens with a disorienting sequence, of an ancient, creaking telescope coming to life, until at last it is ready to turn its lens onto the far more dazzling cosmos. The old telescope represents a more innocent era, before Pinochet’s regime and the subsequent mass disappearances that swept Chile. But to Guzmán, this telescope also stands as a reminder of his country’s rapidly disappearing historical memory, a memory that’s become ever more creaky and confined to the outliers of society — in this case, to those who continue to wander the desert, the sole bearers of witness to the past, working to preserve their dead.

In the Atacama, the technological effort accompanying the astronomer’s devotion to the past — their primary source of information, as the light reaching us from distant objects comes after hundreds, thousands, millions of years have passed — is set throughout the film against the more painful and painstaking efforts of the various women still searching the desert for the remains of family who were disappeared in the 1970s. The shiny modern machines opening their lenses to the sky rise out of the same land that’s host to the ruins of concentration camps and the bodies of the missing.

Guzmán shows us a woman, in the last light, bending down in the hope of finding little more than a shard of human bone that might once have belonged to her husband. This scene occurs not far off from one in which we see a group of astronomers sitting behind their computer screens, excitedly explaining how the calcium in our bones can be traced all the way back to the Big Bang. In this quiet juxtaposition, Guzmán delivers a potent message on the kinds of quests society willingly tolerates, preferring the scientific searches of the deep and distant past over that more painful effort to preserve those recently forgotten and shunned.

The woman, Violeta, goes on to articulate a wish that these astronomers might for once point their telescopes into the ground, to “see through the earth” and hunt for the dead, just as they do among the lifespans of stars. There are others, too, who walk the desert looking for tiny rock drawings preserved in the salty desiccated landscape from thousands of years in the past. Above the Atacama stars die and nebulae form, while inside it so much evidence of human strife remains untouched. Archeology and astronomy in the film are presented as synonymous efforts: as Guzmán’s awing eye takes us to the most brilliant reaches of outer space, he also lovingly and hauntingly returns us to a set of petrified feet in the dust.

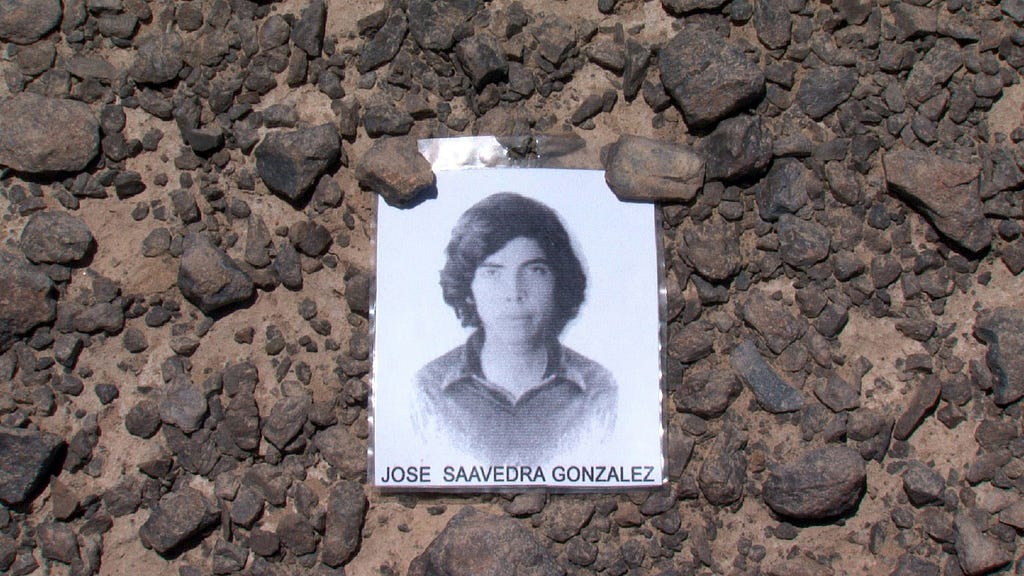

The force of his documentary is in its willingness to equate the universe of personal loss with that of our cosmic longing for answers about where we come from, who we are. The faded faces of the disappeared adorning a glittering sunlit wall become as momentous as the twinkling stars above, from which we receive messages of our collective origin as a species.

Guzmán’s investment in the past is also deeply personal, and his nostalgia, as often is the case, conjures up memories of his childhood. The dust falling through his family home at the very beginning of the film blurs into the cosmic dust that swirls in space.

His childhood, Guzmán suggests, is also synonymous with his country’s, a time when wonder could flourish, when looking in awe at the cosmos did not have a parallel to searching in the desert for those who’d been murdered. But there is also that which we don’t remember, the childhood of our existence which originated with the Big Bang, that first explosion of light to which we owe the calcium in our bones, among everything else.

Close to the end Guzmán reflects, in voiceover, on seeing for the first time the skeleton of a whale in a museum, and believing that the skeleton could serve as the roof of a home for other whales to reside in. We too live beneath the roof of thousands of long-dead celestial bodies. And yet, beneath that brilliant canopy, as the director so hauntingly portrays, we have not yet given sufficient attention to the past and its damages which continue to live with us, equal in part to that in us which is made of stars.

Hannah Lillith Assadi received her MFA in fiction from the Columbia University School of the Arts. She was raised in Arizona and now lives in Brooklyn. Her debut novel, Sonora, is out this month from Soho Press.