Craft

Delhi’s Current Flows On

A walk in India’s capital with Akhil Sharma, winner of the 2016 International Dublin Literary Award

Akhil Sharma stands on the sidewalk waiting for me as I descend the long set of stairs from the Delhi Metro. It is only mid-morning but the street outside Rohini West Metro station is heaving with traffic. I steel myself for the cacophony of shrieking horns and roaring engines. If this were Manhattan, where Sharma lives today, he might be holding a Starbucks cup. But we’re in Delhi, so he sips milky tea from a Dixie-size cup bought from a street vendor for five rupees (about 10 cents). It is mid-February in 2011, Valentine’s Day in fact, and cool beneath an overcast sky.

Sharma isn’t tall, but he seems brighter and more vivid than the other pedestrians around him, as though he were Photoshopped into the wide, bustling street. He wears an orange merino wool sweater, jeans and elaborate running sneakers with shiny trim. In this part of north Delhi, men wear kurtas or collared shirts with polyester trousers, and flip-flop sandals or pleather shoes, not cushioned Reeboks. His dark hair is cropped nearly to a crew cut, and flecked with silver. He wears black wire rim glasses.

Sharma isn’t tall, but he seems brighter and more vivid than the other pedestrians around him, as though he were Photoshopped into the wide, bustling street.

I took the Metro across the city’s sprawl, from New Delhi, the British-designed part inaugurated in 1931, up past Old Delhi, the northern section founded by a Mughal emperor three hundred years earlier. I’ve come to nearly the end of the line, to a northwest neighborhood that tourists have no reason to visit. I had been living in Delhi nearly five years, but I would see the city in a different way: through the eyes of an author whose first book is set in the city of his early childhood and whose second book starts here before its narrator emigrates to the U.S. I’ll follow Sharma as he visits relatives and family friends in three neighborhoods of north Delhi, as though doing a walking tour of his childhood memories. We’ll be traversing different worlds, touring the love and loathing of families, the present overlaid on the past, and places and memories transformed into fiction.

Sharma is the author of An Obedient Father, a novel that won the PEN/Hemingway Award in 2000. In 2014 he will publish his novel Family Life after 13 years of struggle. Writing it was like a “nightmare, like chewing stones, chewing gravel,” he told The Guardian. A couple years after our walk in north Delhi, I sat with Sharma on a bench in Central Park one summer day as he took a phone call from his literary agent to discuss a draft of the novel. When he finished the call, Sharma calmly told me Family Life might be axed.

In 2014 he will publish his novel Family Life after 13 years of struggle. Writing it was like a “nightmare, like chewing stones, chewing gravel.”

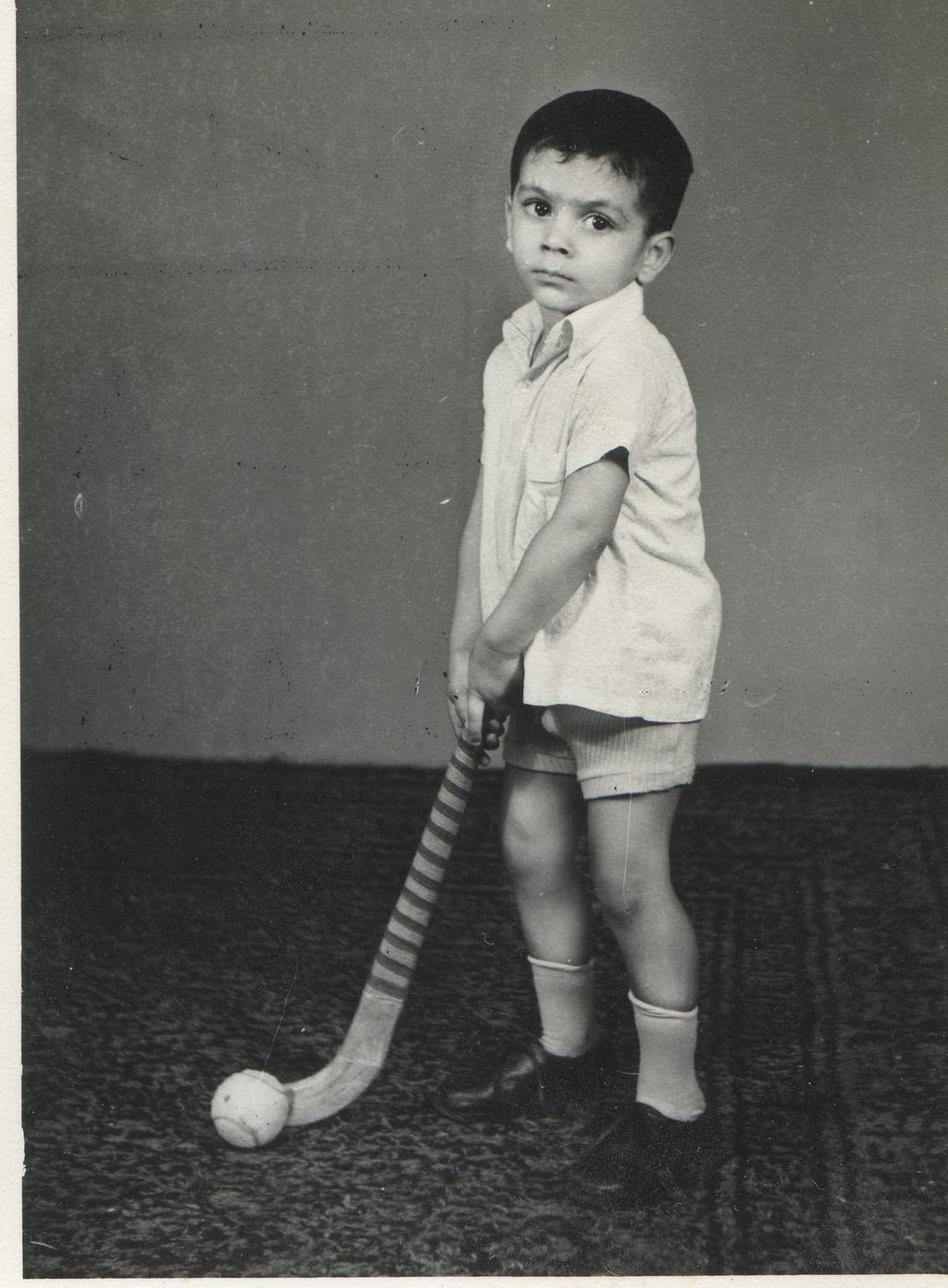

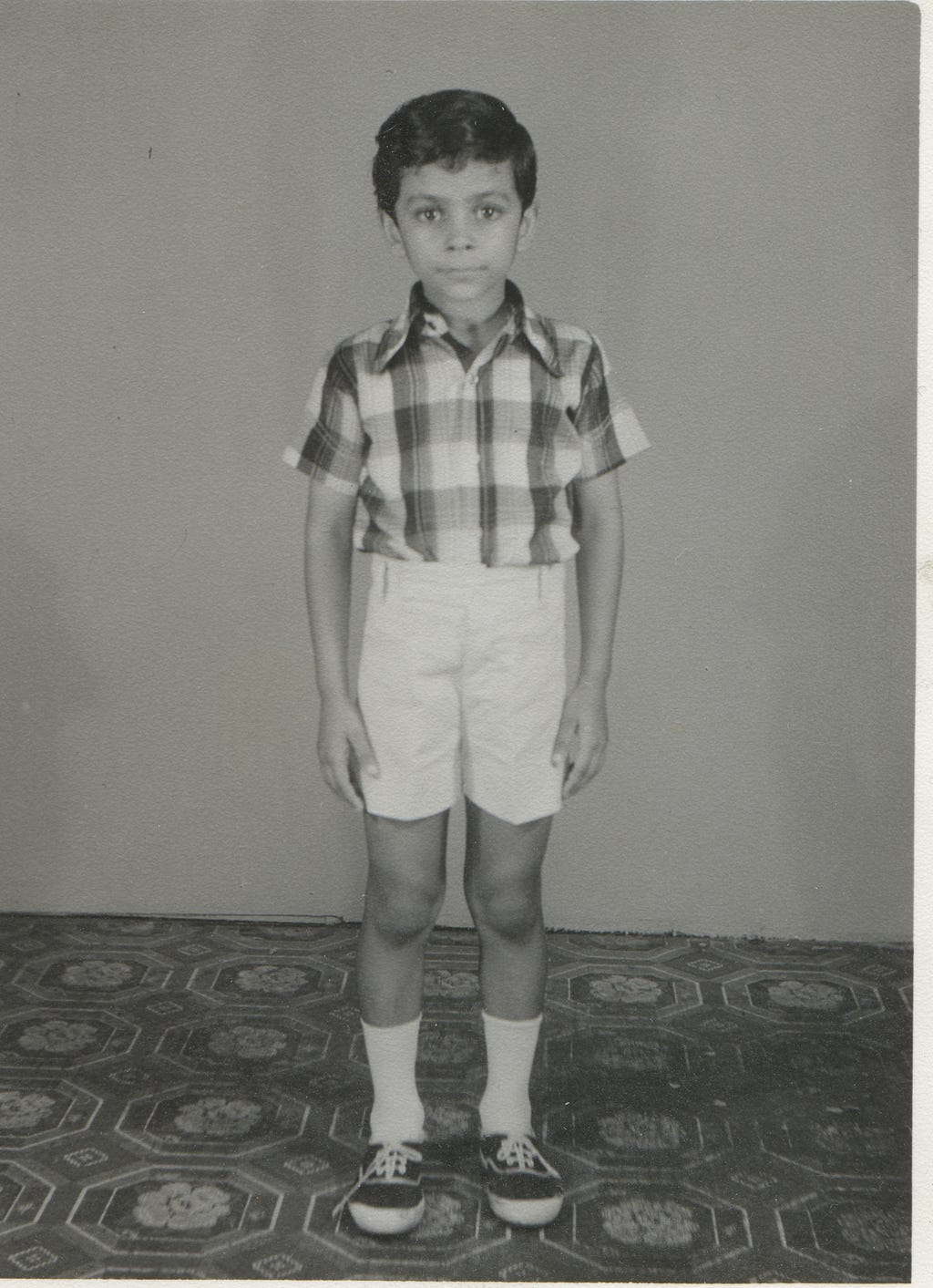

But the toil will pay off: In June 2016 the book will win 100,000 euros for the International Dublin Literary Award, the world’s largest prize for a single novel. But all this is in the future. Today we are focused on the past, where his two novels are grounded. Sharma’s memories of Delhi — quiet dirt lanes where he played cricket, cinemas showing Bollywood matinees, and rooftops where he napped — form the backdrop of An Obedient Father and the start of Family Life. Sharma grew up in New Jersey but spent summer vacations in Delhi with relatives through his early 20s. He was born in Delhi in 1971 and his family immigrated to the U.S. in 1979, when he was eight. A couple years later, tragedy struck. Anup, Sharma’s 14-year-old older brother, hit his head in a swimming pool in Virginia. He remained severely brain damaged for the rest of his life. Family Life is based on the accident and its destructive force on a family.

I was living in New York when I first read an excerpt of An Obedient Father. I was struck by the brutal yet beautifully-written tale of corruption, incest and the unraveling of Ram Karan, a repugnant narrator living in Delhi. I had no inkling that several years later I would move to Delhi as a journalist and that India’s capital would become my home. Places mentioned in the novel — the popular neighborhood of Defence Colony, the chaotic Inter-State Bus Terminal (ISBT), the opulent Oberoi hotel where the lobby smells like citrus, the wide boulevards of New Delhi designed by British architect Edwin Lutyens — would one day become as familiar to me as places in Manhattan. And on this unusual tour, I would get to see Delhi’s streets, houses and landmarks, introduced to me in An Obedient Father, with the ideal guide. The world created in Family Life lies in the future when the book is finally published, but I would get to see its foundations in the Delhi of Sharma’s past.

Our first stop is the home of an uncle and aunt in Rohini, a nondescript neighborhood I hadn’t heard of before. Sharma and I walk on the edge of the street next to the crumbling sidewalk while casually dodging motor scooters and bicycle rickshaws tinkling their bells. Roadside vegetable carts are piled with mounds of large black grapes and stacks of greenish, lumpy oranges. We turn onto a side street lined with homes and shops bearing signs that read “Cyber Café and Computer, Hari Om Communication” and “World Vision India Pentecostal Church.”

Sharma stops when we reach a one-story white concrete house bounded by a wall and metal gate. There’s a four-story apartment block across the street. Laundry hangs from the balconies: shirts, pants, and pink bed sheets printed with big flowers flap in the breeze. The clean smell of laundry detergent powders the air.

We turn onto a side street lined with homes and shops bearing signs that read “Cyber Café and Computer, Hari Om Communication” and “World Vision India Pentecostal Church.”

A gray-haired woman in her 70s with large glasses comes outside and greets us. This is “Auntie.” Sharma introduces me briefly in Hindi and she smiles, then hugs me. Her name is Shanti Sharma and she wears her hair in a long braid down her back, with stray hairs secured by straight barrettes behind her ears. Inside the house, we step into a bedroom where her husband, J.N. Sharma, known simply as “Uncle,” sits up in a raised hospital bed. Uncle has liver-spotted skin, a large, hooked nose and shiny eyes. He greets me excitedly though I can’t understand his murmurs and he grips my hand in his warm fist.

Their surname happens to be Sharma, but Auntie and Uncle aren’t blood relatives. Still, they are precious to him. “There are many, many ways this family saved us,” he tells me. When Sharma was a child, Uncle and Auntie were tenants in his parents’ house in Delhi. Later their paths crossed again in the U.S. when both families were living there.

Sharma matter-of-factly explains that his family and relatives were uneducated, rough and unscrupulous. I’m reminded of the world of Ram Karan, the unsavory narrator in An Obedient Father, an education department administrator who collects bribes from schools. Uncle and Auntie were different from Sharma’s relatives. Uncle was a young economist at Delhi University and seemed refined and respectful compared to Sharma’s family. “They were the only really decent people we knew,” Sharma recalls. “They spoke to children in the formal ‘you.’ They were respectful and never spoke meanly. We assumed they were rich. They seemed like they belonged to a different world.”

If his parents hadn’t immigrated to the U.S., Sharma says he would have been a kid who got into trouble. Becoming a writer would have been unimaginable; no one read books in his family much less wrote them. Later Sharma found out that Uncle pulled himself out of poverty to become educated.

Becoming a writer would have been unimaginable; no one read books in his family much less wrote them.

Auntie and Uncle were also important to Sharma and his family after his brother’s accident. In the summer of 1981 when Sharma had just turned 10, his family was visiting relatives in Arlington, Virginia. His older brother Anup snuck into a swimming pool at an apartment building, dove in, and hit his head on the bottom. He remained underwater for three minutes. Anup required 24-hour care for the rest of his life. He was fed through a stomach tube, cleaned after bowel movements, and had to be turned to prevent bedsores. It was an unfathomable twist of fate for a family already struggling to adapt to the U.S. and cope with its own problems.

At the time, Uncle was an economist at the World Bank in Washington D.C. Sharma’s parents didn’t speak English very well so Uncle helped interpret for doctors and nurses. Auntie came to visit Anup and the grieving family in the hospital every day for the next 11 months. Auntie recalls visiting during the harsh winter and her shoes filling with snow as she made her way to the hospital.

Auntie recalls visiting during the harsh winter and her shoes filling with snow as she made her way to the hospital.

Auntie, Sharma and I are sitting in the living room, which is furnished with a large double bed and heavy wooden chairs. A TV sits in one corner covered with a white doily. The freshly-painted yellow walls are bare except for a plastic clock ticking loudly from its perch above the doorway. As we sit, a young female cook sets stainless steel plates on the coffee table in front of us. Sharma and I each have a bowl of plain curd (yogurt), and a hot parantha, a flat bread stuffed with onions and potatoes. A hunk of melting butter slides across my parantha and settles in an oily pool at its center.

Uncle and Auntie bought this house in Rohini in 1989 for about $11,000. Back then, the area was desolate and undeveloped, a “horrible area” where rain flooded the streets. It was so remote that milk and vegetable vendors didn’t come here, but within two years the area began to develop and shops opened as more people moved there. When the Metro opened in 2004, the area was transformed and property prices shot up. In 2011, the house is worth about $170,000, I’m told.

Auntie wears a teal chemise with a gold paisley pattern, loose mauve pants, a soft blue-gray sweater vest and a purple shawl. This muted palette gives her a gentle, wooly aura. She wears a slender gold bangle on each wrist. Auntie reckons she is 78 or 79. Sharma remarks that she looks much younger than his own mother, who is only 70. “Your mother and I have had different lives,” she reminds him gently.

The years after Anup’s accident were bitter. Sharma’s family was living in Queens but because Anup was hospitalized in Virginia, he and his mother moved there for a year. Sharma’s father had a clerical job with New York State’s insurance department and commuted from New York to Arlington every weekend. The family’s health insurance did not fully cover Anup’s care so money problems created further strain.

Sharma was already a sensitive child and the accident made things worse for him. “I used to cry a lot in school. Everything felt really hard, impossible.” He remembers not wanting to visit Anup in the hospital; he wanted to be home watching TV like other kids. “At that time I felt no gratitude for anyone,” he recalls. “I just remember being there alone.” His mother was resentful of relatives who did not come to the hospital. “She thought if you’re not there all the time you’re being disloyal. The only person my mother feels awe for is this Auntie.”

After the accident, Sharma became “crazy,” he states. “I was an unusually imaginative child and this was an unusually severe trauma.” His childhood whimsies turned into behavior that Sharma describes as OCD-like. It lasted years. Some of the behaviors included walking with his fingers crossed or obsessively counting his knuckle joints to ward off evil. Sharma became terrified of the dark and of supernatural things. At one point, he says, “I thought God would kill me and replace me without anyone knowing.” He recalls a teacher sent him outside because he couldn’t stop crying in class, so he walked into a field while sobbing. That happened after Sharma imagined God spoke to him and asked if he would switch places with his brother. It was his own reply that distressed him: “No.”

“I was an unusually imaginative child and this was an unusually severe trauma.”

After a year in Virginia, the family moved to New Jersey so Anup could live in a long-term care facility that happened to be in a bucolic suburb. “It was the first time I was out of an urban space. I couldn’t believe how green and quiet it was,” Sharma remembers. Eventually the family bought a house in Edison, New Jersey and Anup lived at home.

Home life was excruciating and that experience is reflected in Family Life where the narrator’s family “fought so much that the walls vibrated with rage.” Sharma’s father was overwhelmed with maintaining a house and “became hysterical after moving in,” Sharma tells me. The American tradition of do-it-yourself and hardware stores was an alien concept; in India there are plenty of low-cost electricians, plumbers and workmen on hand. “He didn’t know how to do stuff. I remember him swearing about how to drain the heater.” In Family Life the father descends into alcoholism and depression. “I want to hang myself every day,” the father bitterly tells his son.

Sharma’s mother was already “unpleasant” and the accident only made things worse. She chided people for their incompetence, told them they were bad. “My parents fought like mad dogs,” Sharma says. “My mother’s disrespect for my father was clear.” Even as a child, Sharma was convinced that his parents were not role models. “I thought, ‘This is not the way. This is not going to lead to happiness.’”

At home, nurses cared for Anup in two shifts, from 8am to 4pm and 10pm to 6am. The family helped too. Young Sharma bathed his brother in the morning, cleaned him after bowel movements, exercised him, fed him, read to him, moved him from side to side hourly. The only thing he didn’t do was replace Anup’s “G tube,” the plastic tube that fed directly into his stomach.

Young Sharma bathed his brother in the morning, cleaned him after bowel movements, exercised him, fed him, read to him, moved him from side to side hourly.

I ask Sharma if Anup was ever able to communicate after the accident. He thinks for a moment. “At one point he would sometimes smile. But the last time that happened was years ago.”

It is now past noon and we needed to head to our next destination: Sharma’s childhood home in a neighborhood called Model Town. We get up to leave and say goodbye to Uncle in his bed. Auntie walks out with us and I request Sharma to ask how she can be so resilient. She nods and smiles. He translates her reply: “‘What else could I do if I cried all day. What else is there? This is all a part of life.’”

Outside the house, some marigolds are starting to bud in a strip of soil. Auntie gestures at them and Sharma translates. “She says her husband likes to look at flowers.” He beams at Auntie affectionately. “Oh man, these people are wonderful.”

Sharma and I walk back on the traffic-choked streets to the Metro station. He has been on the Metro only once before so I show him how to buy a token. At a counter, we pay 23 rupees for a blue plastic chip, which we flash over the turnstile. The plastic gate parts in a mechanical whisper to let us pass. “Cool!” Sharma exclaims.

The sleek train eventually emerges above ground onto elevated tracks.

Beneath a slate-gray sky, we bullet past low houses with walls discolored by black smudges. We get off at Model Town station, where Sharma and I step onto a shiny, modern platform that contrasts with the ramshackle houses and garbage piles glimpsed during our subway ride.

The street noise seems even more overwhelming, if that is possible. Buses roar, horns screech and a jackhammer pounds. Sharma waves at the river of traffic and the congested storefronts. “When I was a child, all this was just dust,” he says. We turn onto a side road, past the “Bombay Fire Hairdresser” and a snack stall where men rhythmically pat chapati with flour-covered hands.

“When I was a child, all this was just dust.”

Sharma says there used to be an open sewer here where he and his friends retrieved stray cricket balls. “We used to play cricket in this street because it was so empty.” Drying cow dung patties used to line the road, to be burned for fuel later. There was a swampy wilderness at the end of the road where he and his brother used to roam.

“There were big changes after 1991,” Sharma recalls. “The buildings got taller.” Before 1991 India had a closed, stagnant economy. But reforms ushered in by finance minister Manmohan Singh, the soft-spoken Oxbridge-educated economist who became prime minister in 2004, paved the way for a modern economy. As we walk, a tonga horse-drawn cart, passes us. The horse trots briskly alongside careening cars and its hooves clop loudly on the pavement. This scene is quintessential India: old and new jostling against each other, often quite literally.

Our destination is a three-story house behind a white wall. Sharma lived here as a child with several aunts, uncles and their children in a large extended family. It is dim inside the house. Fluorescent lights wanly illuminate a sitting room occupied by three men. A huge velour tiger skin hangs on one wall. An older man with gray hair sits in a worn arm chair eating lunch. He scoops lentils with his fingers and pieces of roti. This is Uncle Chachaji, a gym teacher at a local school and the second-youngest brother of Sharma’s father. He watches a television showing a Hindi movie. Uncle Chachaji wears a dingy button-down shirt with a blue-checked lungi — a sarong.

This scene is quintessential India: old and new jostling against each other, often quite literally.

Another Uncle, Kul Bhushan Gaur, sits in the other worn armchair. He also has gray hair and wears a blue sweater vest. Sharma and I sit on a twin bed that is made up like a sofa. We sit opposite a middle-aged man who is Sharma’s cousin. I’m told that he’s a lawyer. The cousin sits on another bed-settee and coolly watches me watching him. Sharma tells them that I am a journalist writing about him. “Him?” sneers the cousin. “Why, is he some kind of celebrity?” Sharma doesn’t react.

“He’s not a celebrity,” I reply. “I read his book when it came out.”

“Do you think you will give the right picture of India?” the cousin asks me accusingly.

“I don’t know if it will be the right picture. It will be just a picture, a glimpse through the eyes of one person,” I say.

There are some family photos on the bland walls. Sharma points out the various relatives in the photos: this uncle, that cousin. “There are very few good-looking people in my family,” he observes.

I laugh at his bluntness. “What do you mean?”

The cousin-lawyer interjects. “Our family has rustic roots. We are from Haryana. We are farmers. Short.”

After a moment Sharma heads toward the back of the house to greet another aunt. We enter a cavernous dining room with a heavy wooden table and a refrigerator in one corner. A row of windows lets in stark white light but it doesn’t penetrate the dimness cloaking the room. An older gray-haired woman sits alone at the table eating roti and vegetables from small metal dishes. Her fingers are wet with food. Sharma greets her and we sit. On our way here he warned me that this aunt was extremely unpleasant, possibly crazy, and made hateful remarks to family members. But from their cordial interaction I would not have known.

On our way here he warned me that this aunt was extremely unpleasant, possibly crazy, and made hateful remarks to family members.

Sharma looks around the room with its high ceilings. “For a little child, all these places seemed so large,” he says. “The rooms echoed.”

Near the dining room, he shows me a small outdoor courtyard, a square of empty space at the center of the house. Here, clothes were hand laundered, tomatoes boiled in a cauldron to make ketchup, and wheat was ground with mortar and pestle. Sharma and his brother used to play cricket here too. A rusty metal basketball hoop still hangs from a wall.

We climb to the second floor where another aunt and uncle live. Their living room is brightly lit and it lacks the feeling of stagnant time like in the apartment downstairs. A balcony looks out over a “tank,” a man-made pond slightly larger than a soccer field circled by a tree-lined path. There are plastic boats in the murky green water and a few couples languidly paddle around. For India, it’s quite an impressive view.

“Wow,” I say.

Sharma gazes at the pond. “This is really hard-core luxurious,” he agrees. In Manhattan he lives on the Upper West Side a couple miles from where I used to live near Central Park. In India, we’ve re-calibrated our standards of luxury.

It’s a tranquil scene but noise still drifts through the air: dogs barking, honking car horns, shrieking construction machinery and squeaking pedals turning in boats. “It used to be so quiet,” says Sharma. “There used to be a dirt path around the tank. I remember as kids we found all these discarded medicine capsules outside. We played with them and put them back together. We had so few things as a child.” In Family Life, the narrator recalls that his family was so thrifty they saved the cotton inside pill bottles and also split matches with a razor blade. This frugality “made them sensitive to the physical reality of our world in a way most people no longer are,” the narrator observes.

In Family Life, the narrator recalls that his family was so thrifty they saved the cotton inside pill bottles and also split matches with a razor blade.

We stand outside on the balcony with Sharma’s aunt, uncle and their middle-aged son. They were living in Virginia when the accident happened. This petite auntie in her 70s wears a maroon cardigan over an ecru sari etched with a delicate maroon design. Jewelry glints on her: a diamond stud in her nose, jeweled earrings and a gold bracelet. Raj Kumar, Sharma’s cousin, explains in English that they went to the U.S. where his uncle was working for Washington Gas. He wears a khaki polo shirt tucked into a voluminous white cloth wrapped around his waist.

Sharma chats in Hindi with his aunt and uncle and I glean that they are talking about the accident, trying to piece together fragments of that day. His aunt says that Anup left Akhil at the library so he could sneak off to the swimming pool at an apartment building.

“I remember living in Queens after the accident,” says Sharma.

“No, you were living in R.K.’s house,” his aunt corrects him, shaking her head.

They continue to piece together fragments of memories, like comparing faded pages torn from different books.

Uncle accompanies us to the top floor, to a barsati, a rooftop apartment where Sharma and his family lived for the first eight years of his life. The weather is cool and pleasant and we have an excellent view of the palm trees surrounding the pond. The apartment is vacant so the door is padlocked. Inside, sunlight pours in from two windows onto a dusty bare bed and desk. There’s a small boombox radio on a shelf and an exercise machine that looks like an antique ski machine. The rooms are nearly empty, yet they seem to pulse faintly with ghostly memories.

“I remember being cold and lying in bed in the winter,” says Sharma. “Catching flies on the balcony, feeling a tickle. Watching boring TV movies.”

“You had a TV?” I ask. It was the 1970s in India.

“Yes, but there were no channels.” He pauses and looks around the room. “I remember intense emotions but I have little actual memory of things.”

The bathroom is in a separate room outside on the roof. There’s just a toilet in the corner, a spigot and a drain in the floor. The toilet seat has wide grooved ‘wings’ on the side so someone can squat on top rather than sit if they prefer. “There were few people with western toilets,” notes Sharma. “I was very imaginative as a child. I used to clog the drain with a shirt, so the floor would fill with water, and pretend I was swimming.” This rooftop and bathroom appear in Family Life. At the outdoor sink, beneath a “sky full of stars,” the father brushes his teeth until his gums bleed and he spits blood.

“I was very imaginative as a child. I used to clog the drain with a shirt, so the floor would fill with water, and pretend I was swimming.”

A metal ladder leads to the roof of the apartment, and Uncle is suddenly clambering up. Next, Sharma climbs up and I join them. Electrical pylons squat in the distance. A flock of birds, inky black hatches, suddenly race across the sky overhead. A row of three-story concrete buildings sit across the street. “Those buildings used to be one floor,” observes Sharma. There was a swamp where the pylons stand today, he adds. Family Life describes Delhi in the 1970s: quietness, roads so empty of traffic that children played cricket in the middle of the street.

Back downstairs we have tea and snacks in the more-welcoming second-floor apartment. We sit at the dining table and munch sweet round cookies, rectangular fried ones, and namkeen, a snack of puffed rice, peanuts, chopped green chili and spices. Uncle and Sharma chat in Hindi and I gobble some cookies. They reminisce about the days when they brought their wheat to the local miller for grinding. When they picked up their flour, the miller gave them free cookies. Now they buy their flour at the store, along with packaged cookies. I reach for another one and bite into it.

Our next stop is the Old Vegetable Market, where Sharma used to spend summer holidays with relatives. On the street outside we hail an autorickshaw and Uncle negotiates. For 40 rupees (less than $1) the three-wheeled buggy wends a few miles through raucous traffic to a busy junction with a clock tower. The ghanta ghar, ‘clock house,’ is a white cement obelisk that appears often in An Obedient Father as its narrator stops by a roadside dhaba for a snack or heads home to the Old Vegetable Market. As we drive past, Sharma notes that the clock was stopped for years, its hands stuck in time. The tower’s concrete was cracked and scarred. It was only after India’s economy opened in 1991 that the clock displayed the correct time again.

It was only after India’s economy opened in 1991 that the clock displayed the correct time again.

We get out of the autorickshaw and walk past vendors selling piles of oranges, bananas, garlic and dark, oval berries from bicycle carts. Other street vendors sell all kinds of goods spread on the ground: colorful bangles, plastic toy cars, toy guns, sponges, clown dolls and plastic storage containers. These days, there are no vendors lighting kerosene lamps resembling “iron-stemmed tulips,” as there were in An Obedient Father.

Sharma turns into an alley and we pause at the open doorway of what looks like a temple. It is a temple devoted to a god similar to Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god; it’s also a gym for wrestlers. Inside, two beefy young men wearing only red and green underwear grapple with each other in a wrestling ring filled with rich, brown dirt resembling brown sugar. The wrestlers have other duties, notes Sharma. “They are also minor gangsters hired to seize property,” he adds as the men clutch each other’s waists and bore their heads into each other like young bulls.

There’s a narrow, winding staircase and before long a few young men appear over the banister to watch us. In Hindi, they call to Sharma who asks me, “Do you want to go upstairs?”

“Sure,” I reply.

We climb the stairs. A yellow plastic mat painted with a red circle covers the entire floor upstairs. A poster of an elephant god sits on a window sill next to cones of incense releasing tendrils of fragrant smoke. Half a dozen young men wearing briefs and loin cloths surround us and look at us curiously. Sharma speaks to them in Hindi. He learns that one of the men is a national gold medalist in wrestling. The men seem delighted to have visitors and are keen to show off. They start trotting in a circle like young horses to warm up and seem crestfallen when we tell them we have to leave.

He learns that one of the men is a national gold medalist in wrestling. The men seem delighted to have visitors and are keen to show off.

Sharma and I return to the main road, packed with small shops selling gold, religious paintings, sacks of rice, and Nokia cell phones. We pause at a small church with dilapidated carved wooden doors wedged between buildings. It is a dharamasala, or a rest house, built in 1939 that appears in An Obedient Father when the narrator searches for a priest to give rites on the anniversary of his wife’s death.

We turn down another alley, past a stand where a man presses clothes with a giant iron filled with hot coals, and reach a quiet courtyard with a few homes. Young men lounge on old scooters parked in the courtyard and chat as though they are sitting on park benches. We stand in front of a multi-storied house with a lime-green faux brick façade and rickety balconies that look like fire escapes. A “Happy Diwali” sign hangs over a gray door even though the Hindu festival of lights was in October, nearly four months before.

This is the home of Sharma’s aunt and uncle, his mother’s sister and her husband. Sharma hasn’t been here since 2001. He spent childhood summers in this house and liked coming to India in spite of the scorching summer heat.

A “Happy Diwali” sign hangs over a gray door even though the Hindu festival of lights was in October, nearly four months before.

“I wasn’t lonely because all my cousins were here,” says Sharma. “I didn’t want to be at home in New York.” In India, there were always people around. As if on cue, a man emerges onto the top balcony and leans over to watch us. This house is reminiscent of the narrator’s home in An Obedient Father. I picture corpulent Ram Karan stepping onto the balcony and watching a box kite with a candle floating in the night sky. I imagine him shutting the windows as his daughter screamed so the neighbors wouldn’t hear.

Sharma continues. “We were poor but we didn’t think of ourselves as poor. We had an aggressive desire for education.” Sharma’s cousins went onto professional careers. One is a cinematographer, another a school principal, two are scientists. Then he mentions his family is of the Brahmin caste, so he supposes that is why they still felt culturally elite.

The lugubrious call to prayer sounds from a nearby mosque. By now it is late afternoon and sunset is approaching. Sharma remembers childhood mischief where he used to “catch mice and throw them into the squatters’ colony” — the small warren of shacks nearby.

“You want to look in the squatter colony? It’s going to smell,” he warns. In reality, it’s not bad at all. The lanes in the colony are paved and criss-crossed with electrical wires as power is siphoned from a main line. One house has a hill of tiny flip-flop sandals outside its door, hinting at a TV and a gaggle of children inside.

“You want to look in the squatter colony? It’s going to smell,” he warns.

We return to the main street and pass tiny storefronts selling kachori — fried doughy snacks — and a man carefully cutting a piece of wood on a chattering jig saw. A lean striped cat slinks between parked vehicles. A woman covered with a black veil eyes me as we pass each other. This busy street also appears in An Obedient Father, when riots are poised to break out after the 1991 assassination of prime minister Rajiv Gandhi by a female Tamil Tiger suicide bomber. In that scene, the street was forbiddingly empty as people peered down from their rooftops, “watching like a circus”, in anticipation of lynchings, lootings and riots.

On the main street, a magazine vendor tends to his wares spread on a plastic sheet on the ground. When Sharma was a boy there were only Hindi newspapers and the occasional English-language Indian one. Today the tarp is covered with a colorful variety of Indian and foreign magazines. There are copies of Elle, GQ, Men’s Health. A Cosmopolitan cover blares “Love! Sex! Men!” — a sight unimaginable in the closed India of Sharma’s youth.

We forge on and dodge a couple licking Fudgesicles, then a wooden cart heavy with translucent blocks of sugar covered with a net. Sharma reminisces about eating spun sugar as a child and pushing his way through a scrum of kids to drink a bottle of Campa Cola. Sharma points across the street to a brick rooftop and a sliver of sky between two buildings. As a boy Sharma and his cousins used to watch morning Bollywood matinees at the local cinema then nap on that rooftop. Movies played in Delhi cinemas for 25 or 50 weeks, since there were so few options, recalls the narrator in Family Life. In the distance stands the tall brick chimney of a textile mill. A bell at the mill would ring at 1pm to signal lunch — and disturb Sharma’s rooftop naps.

As a boy Sharma and his cousins used to watch morning Bollywood matinees at the local cinema then nap on that rooftop.

From high up, the rooftops would form their own landscape. I can see why the narrator of An Obedient Father would have concocted a story for his granddaughter about a man who walked across Delhi from roof to roof, using ropes and ladders to cross from the balcony of their home to the squatter’s roofs to the Old Clock Tower.

The oppressive noise and crowds fade when we turn down a narrow lane of residential buildings. Some of them are new and tall, showing signs of recent wealth. Others are unrenovated and still have creaking old wooden balconies with ornate filigree. The afternoon light is growing dim but we see a refined older woman with a bun of white hair approaching us. She wears a cream-colored vest and an aqua salwar kameez. A white dupatta scarf flows over her shoulders.

“Mamiji!” Sharma calls out. This is another aunt and we are going to the house where she lives with a large extended family.

Just then a mustached middle-aged man zooms past on a scooter and stops abruptly. “Akhil!” he cries. This is Akhil’s cousin, the son of the aunt on the street.

The family’s home is an unremarkable multi-storied building. We walk up a menacingly steep stone staircase. “Every single person has fallen down these stairs,” Sharma warns. The home is built around a large courtyard so that an empty shaft of air occupies the center. Sharma remembers spending summers here visiting his cousins. “We’d lay on charpoys and listen to the radio,” he says. We sit in a parlor overlooking the courtyard on heavy wooden chairs with those white doilies.

We walk up a menacingly steep stone staircase. “Every single person has fallen down these stairs,” Sharma warns.

Akhil’s cousin is a lawyer and speaks English but the two of them chat in a mix of Hindi and English. A large plastic doll with blonde hair sits like a mute guest on the settee next to Akhil’s cousin. I look at the black-and-white photos in a recessed alcove next to a blue stuffed bunny. Soon, an uncle with a salt-and-pepper mustache enters the room. He has lived in this house all his life, for the last 75 years.

After many polite protests, Sharma manages to decline invitations to stay for dinner. By the time we leave, it is dark. Uncle accompanies us to the main street, which roils with commerce and noise. Streetlights illuminate the road and shops, including a liquor store, glowing with fluorescent lights. Uncle says there was a neighborhood petition to prevent the liquor store from opening but it didn’t work. Sharma and Uncle gaze at the shop and tsk tsk disapprovingly.

“It’s horrible!” cries Sharma. I’m surprised by their reaction since India is the world’s largest market for whiskey and liquor is ubiquitous at parties and dinners. But this part of Delhi seems still rooted in a more conservative, traditional life — even if a street vendor sells copies of Comso touting sex advice.

The cousin insists on driving us to the Metro station since a group of aunties have to go to a wedding reception. We stuff ourselves into the car overflowing with matronly flesh and saris. I am crammed against the door, practically sitting on an auntie’s lap. We reach the Metro station and I profusely thank everyone as I extract myself from the car. Sharma and I carefully cross the street throbbing with homicidal peak-hour traffic and we enter the Metro station.

The tour ends where it began — at a Delhi Metro station. We will go to opposite ends of the city, Sharma back to Rohini West and me to south Delhi. Before we part ways, I ask about the family member I didn’t meet but who was still at the heart of the day’s memories and conversations, much like the courtyard, that column of air, at the heart of a Delhi home.

Sharma muses about his brother Anup. “When I was a child, I thought I didn’t like him.” After the accident, Sharma remembers, “I cried so much. I didn’t know how much I loved him. I want the people in my life to know how much they matter to me.” This sentiment is echoed in Family Life when it is published in 2014.

Family Life will paint scenes of an older brother boiling frozen corn for his younger brother after school; stopping the bullying of his younger brother at their new school in Queens; and fulfilling his parents’ dreams by passing the grueling entrance exam for the Bronx High School of Science. He would have been a surgeon, muses the book’s narrator. Yet, like the narrator, the brother is also someone who “enjoyed bullying people,” who, fed up with studying for his exams, grabs a kitchen knife and screams at his mother, “Kill me!”

The swimming pool accident cruelly cut short the promise of a young life and cast ripples of anguish over a family for years. Yet “occasionally there were moments of kindness,” says the narrator in Family Life.

In early 2012, I will meet Sharma again in Delhi when he returns with his family to scatter his brother’s ashes in the Yamuna River.

In early 2012, I will meet Sharma again in Delhi when he returns with his family to scatter his brother’s ashes in the Yamuna River. Anup had been ill for years and had difficulty breathing and would aspirate phlegm. One morning, he couldn’t breathe and had a heart attack. Anup was 44 years old when he died after decades of care from his family.

As we stand near the turnstiles to enter the Metro, Sharma and I are the only people not rushing to get somewhere. Waves of people part around us like a river coursing around rocks that futilely block surging water.

“We don’t realize how much people matter to us,” Sharma tells me pensively as we say goodbye. It’s a rare moment of stillness in this busy crossroads, a final moment of convergence before we part ways and Delhi’s current flows on.