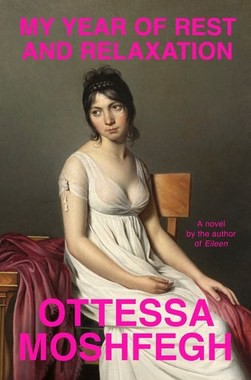

essays

Dream Girls Just Wanna Have Agency

Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation hands power to the sleeping beauty

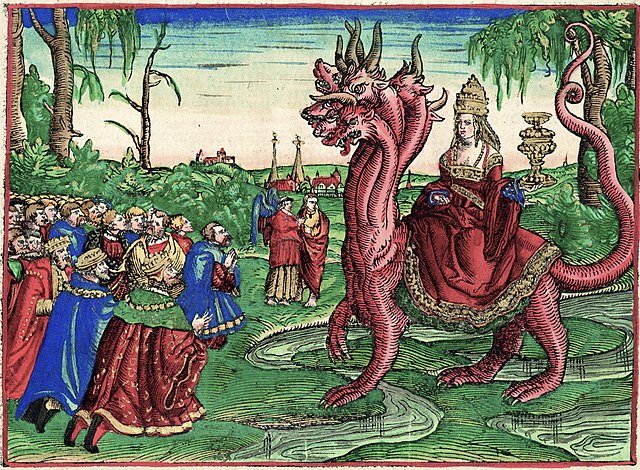

Since childhood, I have been drawn to the various iterations of the Sleeping Beauty/Briar Rose tale. Part of my fascination is aesthetic: I love the stained-glass splendor of Disney’s 1959 film and the ambrosial score and choreography of the Tchaikovsky/Petipa ballet. But there is for me — and, I suspect, for many others — a more psychically resonant appeal to the trope of the sleeping beauty. Perfect and asleep, she embodies the mystery of our subconscious desires. We don’t know what she’s dreaming about; might she be dreaming of us? At the same time, and unlike us half-awake mortals, hers is a mystery that seems capable of being unlocked. She is an enigma if enigmas were perpetually in submission, a “bottom” within an oneiric D/s relationship.

Perfect and asleep, she embodies the mystery of our subconscious desires. Might she be dreaming of us?

Still, I have never been proud of what amounts to a fascination with prone, helpless women and a disturbing narrative. In the story, enchantment turns ugly. The original tales by Charles Perrault and Giambattista Basile relate the maiden’s ravishment by the man who finds her and her persecution by her eventual mother-in-law or the man’s first wife. They arrive at happily-ever-after only after harrowing violations and betrayals. And there’s no getting past the fact that Sleeping Beauty is an infantilized figure rather than a strong woman. It’s not for nothing that in Anne Sexton’s poem, “Briar Rose,” she wakes up crying for her daddy. Anne Rice decided to just run wild with all this wrongness in her series of pornographic novels. What else can you do with this story?

Luckily, Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation breaks the spell. Her novel offers a revisionist narrative of the sleeping beauty, in which she refuses to be objectified and rages with agency. Reading it, I couldn’t help but think of two earlier novellas about lovely girls asleep, Yasunari Kawabata’s House of the Sleeping Beauties and Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel García Márquez. In these three fictions, the sleeping beauties seesaw between accessible and inviolable, but only in Moshfegh’s does the slumbering heroine leap to life.

García Márquez quotes the first lines of Kawabata’s 1961 novella in the epigraph of Memories of My Melancholy Whores: “He was not to do anything in bad taste, the woman of the inn warned old Eguchi. He was not to put his finger into the mouth of the sleeping girl, or try anything of that sort.” (Those who’ve read a lot of Kawabata will know he had a thing for women’s fingers, hands, and arms.) A more direct translation of the Japanese title, Nemureru bijou, would be “Sleeping Beauties”; the English rendering shifts the focus from the comatose girls to the uncanny bordello and the experience of visiting it.

Kawabata was in his 60s when he wrote House of the Sleeping Beauties, which stylistically recalls the sidereal montages of Snow Country, the novel with which English readers are most familiar, more than the energy and cheekiness of early works like The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa. The story may be about the ecstasy old men feel when they pay to sleep next to teenage girls, but it’s unlikely to give you sweet dreams. The unease is established in the opening scene, when Eguchi greets the madam and becomes fascinated by the bird on her kimono sash: “It was not that the bird was disquieting in itself, only that the design was bad; but if disquiet was to be tied to the woman’s back, it was there in the bird.” If Memories of My Melancholy Whores will elegize and even celebrate elderly love and living, House of the Sleeping Beauties exposes the horrors: “Had he not come to this house seeking the ultimate in the ugliness of old age?”

The girls are drugged before he arrives and don’t wake until he has left them, so they have no memory of the nights spent with Eguchi or the other men.

The cold that will turn fatal is stressed from the start. The room in which the clients sleep with Beauty is draped in crimson velvet, a nightmarish hibernaculum. Eguchi smells phantom scents, including a baby’s milk. Soon he is dreaming of deformed infants, which he attributes to his having sought out a “misshapen” pleasure. The girls are drugged before he arrives and don’t wake until he has left them, so they have no memory of the nights spent with Eguchi or the other men. Yet these blank-slate girls have the curious power to usher in memories for their clients. Soon Eguchi is recalling long-lost lovers, his mother’s death from tuberculosis, and his favorite daughter’s marriage, which she rushed into after being deflowered by another man. In between these flashbacks, Eguchi ogles and prods the naked girls passed out beside him. He fantasizes about defiling and killing them. He also imagines them as incarnations of Buddha.

As a former bar hostess in Japan, I’ve long been familiar with the staggering variety of fetishistic options for men seeking company and entertainment in that country. It’s a niche market; I was once offered, based on my Polish heritage, a job at a hostess club that catered solely to men seeking Eastern Europeans, and the pleasures at other clubs I knew of were far weirder than strong cheekbones and bumpy noses. As such, House of the Sleeping Beauties has never struck me as that far-fetched in its particulars. What has always shocked me is the coldness with which the women in the novella are treated. In his final visit, Eguchi sleeps beside two young women, and one — the dark-skinned girl whom he suspects may be a foreigner — dies in her sleep after he turns off her electric blanket in the dead of winter. “Go back to sleep. There is the other girl,” the procuress soothes him. He thinks, “There was of course the fair-skinned girl still asleep in the next room.” The xenophobic and racist implications always jolt me awake at the story’s end.

The aged male characters in both stories feed vampirically on their sleeping beauties, using them to recall the dream of youth.

In many senses, House of the Sleeping Beauties and Memories of My Melancholy Whores are complementary. Kawabata’s procuress thinks of Eguchi as a guest who can be trusted (i.e., she believes he’s impotent), but the madam in García Márquez’s novella scolds the unnamed protagonist when, despite his famed virility, he doesn’t ravish his dormant girl. Kawabata’s tale unfolds in a primeval land of winter, while Memories of My Melancholy Whores languishes in the tropics. The latter has a happy ending. Still, the aged male characters in both stories feed vampirically on their sleeping beauties, using them to recall the dream of youth.

García Márquez’s protagonist is meant to breathe Romantic blasphemy, but look too closely and it becomes hard to indulge him.

Like Kawabata, García Márquez was in his twilight years when he penned the 2004 novella. It opens with a frank confession: “The year I turned ninety, I wanted to give myself the gift of a night of wild love with an adolescent virgin.” His desire is a solipsism; the girl is only the substance of the gift to himself, her personhood incidental. I think García Márquez’s protagonist is meant to breathe Romantic blasphemy, but look too closely and it becomes hard to indulge him. At one point he recounts how, decades back, he raped his maid and upped her salary to account for sodomizing her once a month. He refuses to let the madam tell him the true name of his drugged beloved and christens her “Delgadina.” When the madam announces that Delgadina’s birthday is December 5th, he remarks, “It troubled me that she was real enough to have birthdays.” In other words, for all of García Márquez’s gifts as a writer, this is a book unlikely to be embraced in the era of #MeToo.

After his first night with the fourteen-year-old factory worker who has been procured for him, the narrator casts her as a virgin martyr: “When I returned to the bedroom, refreshed and dressed, the girl was asleep on her back in the conciliatory light of dawn, lying sideways across the bed with her arms opened in a cross, absolute mistress of her virginity.” Indeed, we never see their consummation, nor do we readers interact with Delgadina while she’s awake.

House of the Sleeping Beauties closes with death, Memories of My Melancholy Whores with euphoria. The madam assures the narrator that Delgadina is madly in love with him, and even his lost Angora cat returns. The book refuses to awaken from its own dream.

Eguchi repeatedly casts the other old men who come to the house — the ones who, unlike him, can no longer function sexually — as sad, whereas to García Márquez, it is the women themselves who are melancholy. But the unnamed heroine of My Year of Rest and Relaxation is less sad than furious.

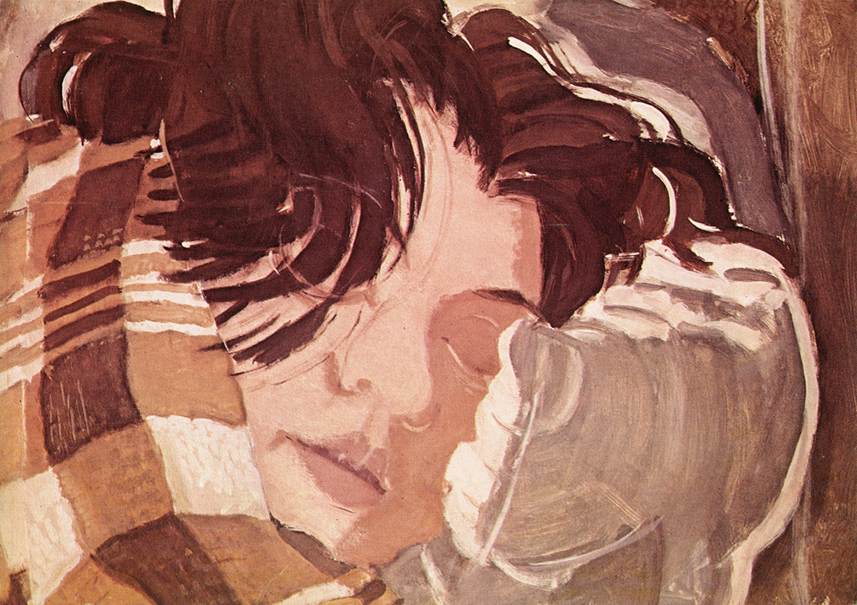

If I’m honest with myself, one of the draws of the sleeping beauty myth for me is that the young woman at its center is faultless. Even if violated while asleep, she cannot be blamed for it. Real life, for most women, is far more complex, with culpability always crouching in the shadow of the bed. But Moshfegh refuses to portray her sleeping girl as a victim to be used or a flawless woman destined to suffer stoically. (Indeed, a sleeping beauty is usually the most stoic victim of all.) Her narrator is arrogant, selfish, manipulative, sometimes mean. She doesn’t shrink from telling lies to get her shrink to dispense as many pills as possible. She’s a drug and sleep addict who doesn’t even bother to shift blame. While she likes sex, she is firmly positioned as a narco- rather than a nymphomaniac.

One of the draws of the sleeping beauty myth is that the young woman at its center is faultless. Even if violated while asleep, she cannot be blamed for it.

What’s subversive in Moshfegh’s novel is that the dream girl refuses to be the blank beauty onto which others project their fantasies. In fact, it is when she starts her obsessive-compulsive sleeping that she stops worrying about her appearance. Before she had looked “like an off-duty model.” Now she shuffles to the bodega in disarray: “‘You have something,’ the man behind the counter said one morning, gesturing to his chin with long brown fingers. I just waved my hand. There was toothpaste crusted all over my face, I discovered later.”

The narrator’s beauty serves a purpose. My Year of Rest and Relaxation questions who is allowed to feel emotional pain. The main character of the novel is ridiculously privileged: Because of an inheritance from her late parents, she doesn’t have to work and owns a stylish apartment on the Upper East Side. She has a degree from Columbia gathering dust in her closet. Her fantastic looks are stressed so often that it reads like a running joke; in the course of the novel, she’s said to resemble Faye Dunaway, Kim Basinger, and supermodel Amber Valetta and is “better than Sharon Stone.” Yet she’s utterly miserable despite all of this good fortune. While others may interpret her plight and its depiction differently — for example, as an indictment of the empty glitter at the turn of the millennium — I believe that Moshfegh went to great lengths to prove that depression and chronic feelings of emptiness can transcend objectively good circumstances. Given the surprise with which the suicides of celebrities like Anthony Bourdain and Kate Spade are greeted, we could use this reminder that mental illness and strife cut across all demographics and pay little heed to worldly success or advantages.

In the other two books, men’s narcissism leads them to fixate on sleeping women; in this book, the sleeping woman fixates on sleep as a way of rewriting societal expectations.

In light of the narcissism of the male protagonists in House of the Sleeping Beauties and Memories of My Melancholy Whores, that of the female narrator in My Year of Rest and Relaxation could also be seen as a clever inversion of gender norms. Sure, it’s a self-defeating mechanism, or at least it would be if the heroine didn’t seem to be growing out of it by the end of the book. But it also means she’s claiming a right to self-absorption that men within and outside of novels have long assumed they possessed. In the other two books, men’s narcissism leads them to fixate on sleeping women; in this book, the sleeping woman fixates on sleep as a way of rewriting societal expectations.

The novellas by García Márquez and Kawabata could certainly be given psychoanalytic readings, but only Moshfegh’s satirizes psychiatry and prescription drug therapy. The narrator chooses her grotesquely incompetent shrink from a phone book; indeed, she is looking for the kind of incompetence that will result in a major drug score. The dreams she shares with this Dr. Tuttle are fabrications maxed out with Freudian currency. In one of them, she puts someone else’s diaphragm in her mouth and performs oral sex on her doorman. But she hoards to herself her true dreams, which process the trauma of her parents’ early deaths. She insists on remaining opaque in the power struggle of psychiatric treatment and uses the doctor for her own purposes, fully availing herself of the vast pharmacopoeia available to anyone who can afford visits with such a doctor.

Despite her abuse of the doctor-patient relationship, she seems to honestly, tragicomically, expect her prolonged period of sleep to rejuvenate her. As she puts it, “My hibernation was self-preservational.” At face value, this belief sort of makes sense. After all, isn’t sleep supposed to heal us? In this way, My Year of Rest and Relaxation intersects not just with the sleeping beauty myth but with the oppressive rest cure of “The Yellow Wallpaper” — except in this case, it is the narrator directing the cure.

Narrative logic would seem to demand that the sleeping girl be the object, not the subject, of the story. Moshfegh’s novel manages to make the sleeper the subject.

However misguided such actions may be, it’s notable that they are actions. Narrative logic would seem to demand that the sleeping girl be the object, not the subject, of the story. One of the intriguing things about Moshfegh’s novel is that she manages to make the sleeper the subject. In House of the Sleeping Beauties, by contrast, Kawabata frequently uses the causative-passive form to describe the girls’ state; in English, this construction is rendered as “had been put to sleep.” The causative-passive form in Japanese is often used to connote a sense of victimization, of something bad being done to a person who lacks agency. Moshfegh’s narrator, on the other hand, goes to tremendous lengths to put herself to sleep with soporifics, again and again. She’s causative-active.

Near the end of the book, she does briefly become an object as she poses, while heavily drugged, for a video series by a repellant and pretentious artist-of-the-moment. One review of the piece describes her as “a bloated nymph.” But her ability to dismiss the objectification and return to the outside world once her hibernation is over makes it clear that she feels empowered and, now, very much awake. The protagonists of House of the Sleeping Beauties and Memories of My Melancholy Whores were both at the end of their lives, but Moshfegh’s is poised for the future on her Louboutin stilettos.

Kawabata’s tale is set in snow and Garcia Marquez’s steams with heat, but Moshfegh’s story spans four seasons. Like House of the Sleeping Beauties, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends with a death. Chekhov’s gun takes the form of an open window in this book. When the narrator settles down for her four-month-long sleep, she vows that if she doesn’t feel better by the end of it, she will commit suicide by jumping out her window. However, the character who leaps through an open one in the last scene is her toxic best friend Reva, and not by choice. A novel set in Manhattan that begins in summer 2000 and specifies a year’s time frame can only have one ending: something to do with 9/11. (In this sense, the one thing that lacks agency in this novel may be, to a small extent, the narrative itself.) The woman falling from the tower — a terrible inversion of another fairy tale trope, of maidens who must be rescued from high rooms — might as well be one of the sleeping beauties depicted in earlier tales, who needs to be shaken awake at all costs.

One thing’s for sure, though. We haven’t heard the last of the sleeping beauty. She (or perhaps a beauty of another gender) will keep speaking through contemporary literature even as she struggles to free herself from sexual predation and other bad dreams.