Books & Culture

Expanding the Twin Peaks Universe

Twin Peaks co-creator Mark Frost on mythology, magical realism and his penetrating new novel, The Secret History of Twin Peaks

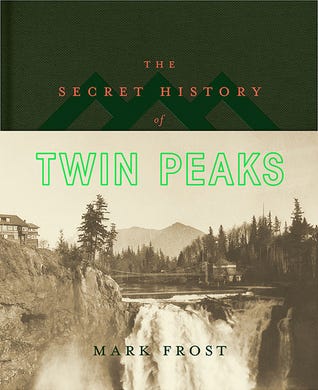

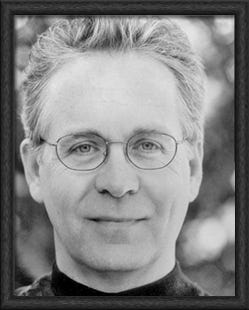

Few places, fictional or otherwise, invoke as much mystery or devotion as Twin Peaks, the eponymous setting of the 90’s television show that will see a revival in 2017. Mark Frost, the show’s co-creator and writer, is also an accomplished author of novels and nonfiction, his latest being The Secret History of Twin Peaks (Flatiron Books), a unique epistolary endeavor that charts the underbelly of the town from the days of early exploration in the Northwest.

Frost’s novel invites readers to solve a mystery as they read. As the narrator, cloaked in anonymity of known simply as The Archivist, unravels the history of the town through FBI case files, it is up to the reader to pick up clues as to who is taking us on this journey. For diehard fans it’s a chance to put their expertise to work, and for casual fans it develops a sense of devotion to the text, pulling them along as they read.

In a coffee shop near Portland’s Powell’s Books, Frost and I recently sat amid a din of baristas and a soundtrack of oddly fitting music such as Nick Cave’s “Red Right Hand.” As a longtime fan of Twin Peaks it was overwhelming to spend time with one of the people responsible for the show’s existence and its mysteries, but having lost myself in the experience of the novel, which is buoyed by a striking design concept of artifacts and documents, I was eager to discuss the idea of crafting mythology and the blending of history and fiction.

Ryan W. Bradley: The initial announcement of the book said it was going to bridge the gap between the original series and the new one, but it doesn’t do that at all. Was that misreported or did the project evolve away from that?

Mark Frost: It was misreported. It was a generic press release that was put out before we really even knew what the book was. I quickly realized there was too much proprietary information that would have been contained in those gap years and might have been detrimental to the eventual series.

Bradley: So, that wasn’t something you ever thought about doing with the book?

Frost: Well, the series came first. The book was the second step. I knew I wanted to write the book, but even back when we were finishing the second season I used the success of the show to parlay a contract for my first book. That’s what I’d always really wanted to do. I started writing at seven, eight, or nine. That was my first love as a storyteller.

Bradley: Before you went into TV.

Frost: Yeah. I was a playwright. I studied at Carnegie Mellon. I was really thinking that was going to be my path and I did do that for seven or eight years and it was fine. I was having plays produced at various places in the midwest. But it was really about poverty. I got involved with a public television station in the Twin Cities. They hired me to make a documentary, and it was the act of making that movie that got me back into realizing… I’d already spent one year in Hollywood after my junior year of college writing television shows. At nineteen I was writing on Six Million Dollar Man, which felt silly on one level, but it was fun to make money. I didn’t grow up with very much, and I enjoyed being able to have a life. So, when it was time to go back to that in my late twenties, I headed to L.A. That was the right decision, it turns out. It took fifteen years, but I finally was able to figure out how I could get back into prose, and that’s been my main focus ever since.

Bradley: And you’ve written nonfiction, too, which probably helped in blending the material that makes up The Secret History of Twin Peaks.

Frost: Very much so. And having done a fair amount of documentary work, it’s a different sort of storytelling. In a film format you shoot first and ask questions later. The material evolves out of what you collect. It’s more like a found art than something you start from scratch.

Bradley: Was this format— the conspiracy theories and the alternate history of the United States — something you collected prior to starting work on the book?

Frost: My first thought was that I wanted to expand and broaden and deepen the universe of the show, and to do that I wanted to go back in time. That was the one dimension we hadn’t played with yet. I had to start with the arrival of American explorers in the area. Particularly with this area [the Pacific Northwest] and its explorers — this was a formative moment in westward expansion. And then I realized it was going to take me into this alt history — the Wilkinson conspiracy, the Meriwether Lewis murder conspiracy, which I didn’t know much about when I started this, only that there were peculiar circumstances and that perhaps the dominant version of what happened to him was not true. So, that became a really good template to set the idea of the book in motion: things are not often what they appear to be. And there was this tension that I have with the Archivist articulate, that fundamental difference between mysteries and secrets. Then I had the theme to work with.

Bradley: The book’s design, which is full of ephemera so to speak, is such a big part of the storytelling. You’ve mentioned how intensive that experience was, working with the design team. Were you involved in the source work and constructing how it would look?

Frost: I made recommendations at the start. Finding the sources was a little out of my purview, so I relied on them. I simply reacted to what they came back with. My goal was to try and tell as much of the story through the documents as possible. Even in my first and second draft I changed a lot of what had been more or less straight narrative from the Archivist into documents, in order to try and make that a predominant component.

Bradley: Was that part of the concept from the beginning?

Frost: Yeah, the idea of the dossier was a pretty early concept for me and then I really wanted to take it as far as I could. I thought it was a really good marriage of function and form.

Bradley: It adds such a strong dimension.

Frost: I think for a book associated with a visual experience — a television show — a strong visual component felt appropriate. The more we could make that part of the experience, even a visual experience of documents,the better. I wanted to get as much of a sense of authenticity as possible.

Bradley: There’s something really unique about using realism to provide an escape. A lot of people read fantasy or science fiction, etc. out of escapism, but I’m really interested in reality because it’s so hard to understand even while living in it. You can have a great marriage and great friendships, but when you really start thinking about how different you are from all those people it gets really confusing as to how you maintain those relationships. There is so much going on behind our vantage point of those people.

Frost: If you can drop something into a person’s life that cuts a hole in that veil for a minute…It always seemed to me, from a shamanistic standpoint, to go back to Joseph Campbell, that’s what art is supposed to do. That’s what storytelling is supposed to do. That was its function in a tribal society. It was supposed to cathartically get you out of yourself and give you a point of view on yourself that maybe you didn’t have before. So, I was hoping to do something here that would be a sort of American magical realism.

Bradley: It’s the flipside of Americana. And the show is that way, too.

Frost: There are a lot of iconic, sort of comfortable things that we cling to. [The show] captured that for a lot of people, and I think it revitalized a lot of those tropes. But then you think, but wait a minute, that’s not all there is, that’s just a thin veneer on top of life. What’s really going on underneath it? My experience of small towns was that all you had to do to experience a strange and alien world was to go visit your neighbors. There’s something weird going on around you at all times.

My experience of small towns was that all you had to do to experience a strange and alien world was to go visit your neighbors.

Bradley: There’s an advantage to what you guys did with the town — it becomes a character. It is both a villain and a hero and a mysterious neighbor. It gives you so much room to play in a novel like this.

Frost: Yeah, it becomes a lens through which you see all of this. That metamorphosis — from the frightened kid you meet to the cynical hardened investigator all the way to the perhaps enlightened fool. By the end of it, I thought that was a really interesting journey.

Bradley: You mentioned Joseph Campbell, which brings us to mythology, a big interest of mine. Aside from the classic idea of mythology, Greek or Roman or Norse, there is so much that we see now that we don’t even think of as myth. Americana is a kind of mythology. In the moment people didn’t think about diners as anything but restaurants, but now they are iconic, they are symbols.

Frost: It’s a tricky thing. It can turn into kitsch really quick if you’re not careful, or it can lead you toward something that seems central to the experience of being alive at a certain place and time. And that’s what we want it to stand for because it’s a shared experience. It’s a commonality. And if you grew up in my era, diners bespoke a certain experience and a certain way of living. It was branding before everyone knew what branding was. Then there was Edward Hopper and it got identified as that early on.

Bradley: Originally, when the show was first on, you guys thought you would be getting a third season. Were there stories that you were ready to tell that found their way into the book?

Frost: Yeah, we had started to do some preliminary work on season three way back when, and honestly I hadn’t kept any notes, but there were things that I was able to recall that were good breadcrumbs to follow going forward.

Bradley: Television shows, film, music, and books that develop cult followings become their own pop culture mythology. When you started writing the book was there a sense of pressure to follow that mythology and to work within the world that had created it?

Frost: The thing that folks have to remember is that we created the mythology. We dreamt it up, so I think that gives us a certain amount of license to take it wherever we choose. There have been a few complaints that there are things that aren’t consistent with the show. Well, the book is comprised of documents, not of words on stone tablets that we found under a burning bush. Documents by inference, through all human endeavor, are riddled with human imperfection. I actually included some typos on purpose and misinformation to simply duplicate reality. I know that creates a little cognitive dissonance for people who like to use the word “canon,” but canon is a little bit of a pretentious word. It’s a TV show, it’s not the collected works of James Joyce or Samuel Beckett. If we want to change it, we are going to change it and that’s our prerogative. And that also reflects reality. Reality is fungible.

We created the mythology. We dreamt it up, so I think that gives us a certain amount of license to take it wherever we choose.

Bradley: It’s easy to get caught up in doing service to fans, but that also makes it really easy to lose track of the story that you want to tell, as the writer or as the artist. That’s probably a sign of what you’re talking about. You focused on telling the story that you wanted to tell. And, as you well know, you can’t please everyone.

Frost: Oh no, and you have to know that very early on. That’s impossible. That’s apparently the job of politicians, not artists. The notion that stories can vary or have inconsistencies or colliding facts also should be analysed when all is said or done. There is very little about the show or even the book that is accidental.

Bradley: It should be obvious to anyone who reads the book, or even flips through it, that this was a very meticulous project. The intent was there, it wasn’t slapped together as a tie-in. It’s very purposeful in its existence.

Frost: Yeah, it was a piece of work that I wanted to be able to stand on its own two feet. It obviously draws on a lot of material from the show, but for me it needed to be its own thing as well and that certainly was my goal.