interviews

Forget Prince Charming, the Women in These Fairy Tales Want Revenge

Amber Sparks reimagines happily-ever-after in "And I Do Not Forgive You"

There are a few writers who we trust as the de facto town criers of literary twitter—they always seem to have their finger on the pulse of the community, and you can trust them to have a level headed opinion on any news item, literary or otherwise.

I think we can all definitely agree that Amber Sparks is one of those writers. And now, we’re lucky enough to have a new collection of fiction from her that serves a similar purpose—And I Do Not Forgive You understands and extrapolates on the tenor of our current moment through stories that relate how women experience anger and revenge.

Sparks birthed this collection through the anger of the #MeToo movement and the supreme court hearings of two years ago, but the stories resound just as much today as they did when she first wrote them, because the patriarchy still exists and women are still fighting within it every day.

I talked to Amber Sparks about the bloody history of fairy tales, the fantasy of revenge, and the catharsis of writing about anger.

Rebecca Schuh: You can really feel the anger at the heart of the book, at the world and the patriarchy, and we are in this exact moment with the presidential primaries fueling so much of that every day. I wanted to ask how you’re feeling with the primaries, with your work, with your feminism. How that’s relating to your day-to-day feelings?

Amber Sparks: There’s so many feelings right now. One of the things I was trying to do with the book was a sense of catharsis. That’s the point of the revenge, right, is to come to some sort of catharsis and some sort of conclusion that would be cleansing. With the book, I get to have that weird great feeling of conclusion, this sense of revenge that I can have that I don’t actually get to have in real life.

In some ways, it’s kind of fun talking about it right now because it’s almost like a little fantasy that you can escape into. It’s an interesting reminder because when I first talked to Liveright and my editor about the book two years ago, I said: “I do hope that #MeToo and the women’s anger is still part of the conversation in a few years.” And of course, I had no idea that this is where we’d be and it would be a more relevant book than ever.

RS: I’m interested in what you said about catharsis. It’s a metaphorical word but it’s also a very physical word. Did you feel that you got physical relief when you were writing the stories?

AS: Yes, oh yes. That’s why I actually started writing this book. I’m working on a novel, but I felt so angry and so blocked and so frustrated that I felt like I had to do something. And Lord knows the only actual skill set that I have is writing. I was like okay, I’m just going to write. I called them my revenges. I said I’m going to write some little revenges for myself to make myself feel better. It definitely felt physically better as well as emotionally better. I would write these things and I would feel like oh, okay, now I can work on something else. I can get rid of those feelings for a few minutes. I never thought about even putting it into a book until I started talking to other women who were like “why don’t you make that a book? I would read that, I would love to have that sense of catharsis.”

RS: The first story in the collection involves this very traumatic friend breakup. When I read it and reread it, I couldn’t find evidence as to what caused the friend to ghost her best friend, leaving the reader as much in the dark as the ghosted friend. Was that an intentional move for you? Making the mystery not solvable?

I want to give women the idea of the ability to exist for the sake of herself.

AS: Yeah, absolutely. I wrote that after reading an advice column where somebody wrote in about being ghosted by a friend and didn’t know why. I thought “my god, that is just horrible. I couldn’t think of anything more horrible.” You really don’t have any sort of recourse, the kind of recourse that you would have if it were a family member or lover. I started thinking about that and wrote the piece. And it was funny because after I wrote it, I had so many people write to me or message me and were like the same thing happened to me. It’s just such an ultimate horror and such a particular horror for our modern society to think about, being ditched and you have no idea why and no real way to find out.

RS: Thinking about what you said comparing it to a romantic ghosting because even if you’re banging on your ex-lover’s door, and you’re acting like oh my god I just need to know, people will call you crazy but they also will kind of get why you’re doing it. It’s happened, that’s common, that’s how exes are.

AS: People might call you crazy, but they get it. If you went and banged on your best friend’s door, people would definitely think you were out of your mind and would call the police on you.

RS: The other thing that’s so disturbing with friendship is obviously we all want our relationships and marriages to be completely open, we know what our partner is thinking, but it’s very common that people have a secret that leads to something bad. You’d think those are the things you’d tell your best friend about.

AS: Exactly. The people in the story, they share everything, they know everything about each other. The larger thing that I was trying to get at is our alienation in our current society. The way that people who live in the city live so weirdly apart sometimes.

RS: And the acceptance of alienation. To know how common, it’s a part of modern life. The next thing I wanted to talk about is the story “A Place for Hiding Precious Things,” where the young woman has to escape her father’s incestuous desire after the death of her mother by hiding in a donkey skin. Where did that story originate?

AS: It actually comes from a fairy tale called “Donkey Skin.” It’s a very loose retelling of that fairy tale. The protagonist is a young princess whose mother dies and her father, the king, decides he has to have the next best thing, the next most beautiful woman in the world, who happens to look just like her mother did. And so she has to escape with the help of her fairy godmother. In that fairy tale, she finds a handsome prince, and of course, they get married and live happily ever after. And there is a cake and a ring and some other elements of it that I kind of threw in.

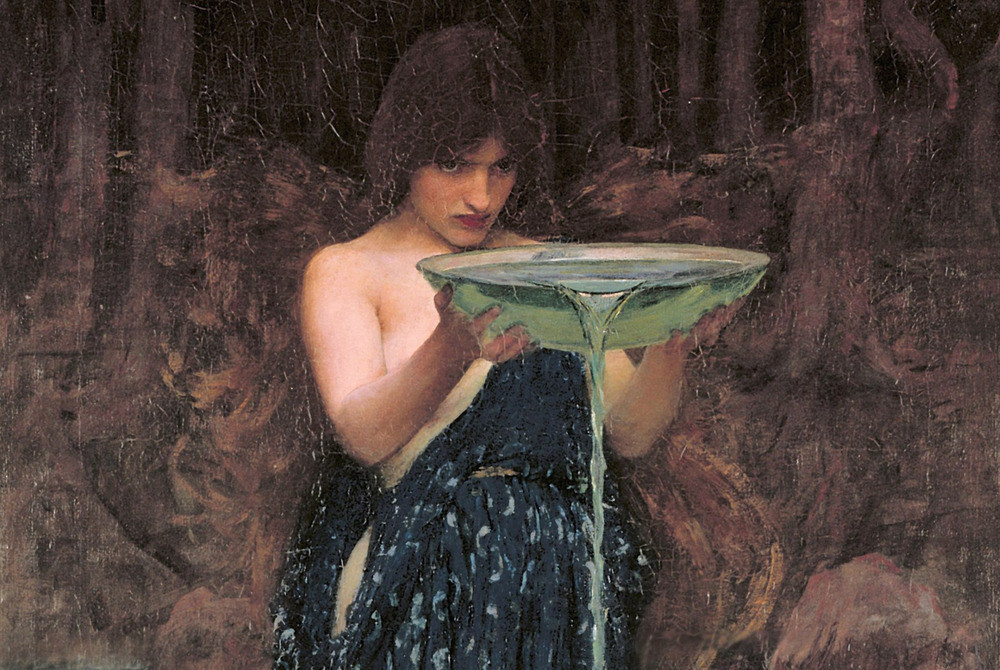

It’s one of my favorite fairy tales, and because it’s just so off the wall, it’s really wild and weird. The way that she disguises herself when she runs away is she kills a donkey, her father’s favorite donkey, and wraps herself in the bloody donkey skin. I’d always wanted to write this because it’s such a feral fairy tale, but every time I tried to write it, I kind of got stuck at the part with the prince. And then after a while, I figured out that I don’t think the happy ending for this girl is ending up with the person. It’s such a feral story, it deserves a more feral ending. She can transform herself in a way that has absolutely nothing to do with running from one man to another.

RS: I love that aspect of it. She experienced the men and then…

AS: She tried it out and it didn’t work out so she’s living in the forest now.

RS: I’ve read several books in the last few years that are taking on the retold fairy tale, I love watching that develop as a modern genre. When did you start working within that? Are there other writers you took inspiration from?

AS: Angela Carter, Helen Oyeyemi, and Kelly Link have been doing it for a while. I definitely took inspiration from folks like that. Matt Bell has rewritten a lot of fairy tales. It’s something that I think kind of started with the modern feminist movement. There was a story that came out about how fairy tales are actually much older than we thought that they were. The sort of men that we think of collecting these tales and being the first, the Brothers Grimm and stuff, they were actually much older than that. Thousands of years ago, as opposed to hundreds. There’s sort of this interest and a resurgence in going back and subverting some of these traditional stories, and digging into the older origins. A lot of versions of these stories that we have are sanitized. If you actually go back and look at some of the more original stories, they were really fucked up. Cruel, violent, a lot of them were really bent on revenge and retribution in crazy ways. It’s fun to go back and find the…I don’t think you can really call them feminism, but you can find the service to women in those particular stories.

RS: It’s interesting, I hadn’t heard of that particular story, but when I was a kid, my sister and I, we really loved gory stuff. And there were two or three fairy tales we were obsessed with, and one of them was the girl with the red shoes who has to dance forever or get her feet cut off, and the other one was the little match girl where she ends up simply dying in the street.

In traditional stories, your protagonist is going to end up with a romantic partner but that’s not the only way to be happy.

AS: I had this book of Hans Christian Anderson stories that was at my school library when I was in elementary school, and I used to go and check it out over and over again just to read those stories. I was obsessed with them, and my mom was like they’re so weird. He kept that weird violent stuff that got sanitized out of a lot of the other versions. He kept those in there. That totally appeals to kids, kids working out their fears and trauma through horror. Find the worst thing and then okay, you can feel better, you’ve faced that demon.

RS: Speaking of worst things, you had this dichotomy of “the release of loneliness being the best thing for a character and possession being the worst” I found that so interesting, because usually loneliness is what people are afraid of, and possession is the desire.

AS: I’m obsessed with the idea of loneliness not being a bad thing. And people will be like oh, being alone, and I’m like no, specifically loneliness, the emotions that are attached to it—that they might feel alone and feel your aloneness and embrace that.

In traditional stories and traditional romance, your protagonist is going to end up with a man. Or if you’re reading particularly enlightened romance, with a woman. Either way, they’re going to end up with somebody, a romantic partner, but that’s not necessarily the only way to be happy. A huge growing number of women are single, want to stay single, and have no interest in having a long time romantic partner. I think it’s great, that there’s a freedom in that. That maybe we can’t entirely experience unless we are alone. Especially for fairy tale heroines and the kinds of people who are constantly being sought after by men for their own various reasons. I want to give women the idea of the ability to exist for the sake of herself.