interviews

From Suicide Hotlines to Taxidermy

Poet and essayist Anna Journey on the art of the associative leap

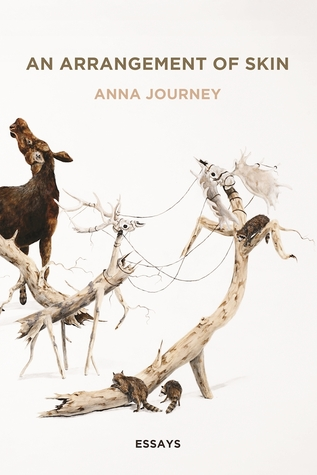

I came late to the party of Anna Journey’s wisdom and wit, but I was thrilled to be ushered into the room after reading her latest collection of poetry, The Atheist Wore Goat Silk (Louisiana State University Press), and then devouring her stunning debut collection of essays, An Arrangement of Skin, out now from Counterpoint. In both her poems and her essays, Journey makes the imprecise and the expected her enemy.

Journey has a preternatural gift for artful swerving and associative shifting, so that—in the title essay, for example—a recollection of a breakdown and an ensuing call to a suicide hotline opens into a consideration of taxidermy and lyric time. In writing about her mother’s penchant for telling macabre stories at the dinner table, Journey makes a connection to campfire songs, and suddenly we’re delivered into a new space the essay has created to argue for the cultural importance of American roots music. And in providing the reader with a portrait of a tattoo artist named after a pirate-themed rum, Journey is concurrently turning our attention to the ways in which we inscribe our skins and spirits through the intimate gestures of ink. All of this without the work ever feeling as though Journey has her thumb on the scale, which is no small feat. This restraint is a mark of brilliance as well as an act of generosity. It’s a vote for the reader’s autonomy and an invitation to wonder and wander inside the latitudes laid out in the work; spaces in which Journey is both our cartographer and our fellow traveler.

It was a galvanizing gift, having the chance to speak with Anna via email about her work.

Vincent Scarpa: One thing I admire about the essays in An Arrangement of Skin is that what seems to motivate so many of them (their origin story) is as simple — and as complicated — as curiosity. It isn’t hard to imagine someone asking you, “So, why did you take up taxidermy as a hobby?” you responding, “I was curious about it,” and the other person being unsatisfied by that, if not suspicious. But I love that the essays advertise that curiosity as their raison d’être in favor of constructing some kind of false framework upon which to build. Reading them, I felt as though you weren’t seeking to indict, to expose, to philosophize, to self-evaluate, to self-synopsize, et c.— though, of course, much of that happens via the act of writing, and is deeply pleasurable — so much as you were seeking to be a student of swirling environments — personal or otherwise — and to report back from that place. Is this totally off-base, or does it strike you as at least somewhat like your modus operandi?

Anna Journey: I would definitely call curiosity my modus operandi. What’s it like to slice open a starling and taxidermy its body? How does this gesture connect to our narrative impulse? To aspects of beast fable? To freezing time in lyric poetry? Why did my dad buy a leather trench coat from a German immigrant at a Bolivian airport in the seventies if he believed the salesclerk was probably a Nazi in hiding? Interrogating one’s own curiosity makes for an exciting mode of inquiry for essayists — it keeps us circling.

I think curiosity always informs my choice in subject matter. I also think it helps me navigate and develop metaphor. In my essay “Modifying the Badger,” for instance, based on the second class I took at the taxidermy studio Prey, in Los Angeles, I arrived at a metaphor for the ways we shape-shift throughout our lives, becoming different versions of ourselves. During the taxidermy class, we got to choose our specimen (coyote or raccoon) from a pile of tanned hides. My instructor had mentioned that the person who picked the largest raccoon — the “boar” — would need to modify a cast polyurethane badger form (with a Dremel tool and several saws) to fit the skin, since the commercial raccoon forms were too small for the big guy. I knew I had to choose that specimen. The whole scenario seemed to me like a macabre fable or Ovidian myth set in a hip, ethically sourced taxidermy studio. Transforming a badger into a raccoon? How could I resist that metaphor?

In another essay, “Little Face,” my curiosity about and fascination with the renowned cosmetic dermatologist Dr. Fredric Brandt — whose suicide and blank, Botoxed face haunted me — lead me toward the essay’s governing metaphor. I began a meditation (etymological and personal, social and lyrical) on the image of the face. The trope of the face and the facet (derived from facette: a “little face”) suggested a “faceted” structure I might use to juxtapose various narratives in the essay. So finding that figurative thread helped me stitch together a number of anecdotes: Dr. Brandt’s ghoulish alterations of his mask-like face; my own dermatological adventures in chicken pox scar removal; a Grimm fairy tale about youthful transformation gone grotesquely wrong; and an ill-conceived art project at the elementary school at which my mother works that involved digitally aging photographs of first graders so the kids could glimpse approximations of their future wrinkled, one-hundred-year-old selves. I think curiosity has a lot to do with my compositional approach as well as my interest in the layered textures and associational possibilities of metaphor.

VS: The Atheist Wore Goat Silk begins with the poem “Upon Asking the Cashier at Kroger to Scan That Old Tattoo of a Barcode on My Forearm,” in which we learn that the speaker, when she was nineteen, tore a barcode from a grocery store coupon and got it tattooed without ever having known what the barcode designated. The cashier tells her the barcode is for “a dollar sweet potato,” and later the speaker wonders why she’s waited ten years to investigate this, to learn — or relearn, as the case may be — “I’ve always been sweet but slightly / twisted, I’ve always been // waiting to disappear like this, / bite by bite, into someone’s mouth.” This struck me as an interesting entry point into asking an otherwise not terribly interesting question about how long the essays in An Arrangement of Skin have been accruing on your end before making their way into the container of this collection. Did you desire a sense of delay between what a given essay adumbrates — which, in my clumsy analog, I suppose would be the tattooing of the barcode — and then the writing of the essay itself — the scanning for meaning?

AJ: The delay depends on the essay’s subject. Sometimes I’ve been trying to write about a subject for years (like my childhood in South Asia) and in other cases the time frame will be much shorter. Sometimes there’s barely a delay at all and I’ll begin an essay, believing I’m writing about one thing, and then stumble into the piece’s deeper subject.

In the case of the title essay, “An Arrangement of Skin,” I’d planned to write about my visit to Deyrolle, a spooky two-hundred-year-old house of taxidermy and museum of oddities in Paris, on the Left Bank’s rue du Bac. I thought: I’m going to write a meditation on taxidermy. After Paris I rented a dark, narrow apartment in Prague with exposed cedar beams and an ornate green-and-white tiled ceiling whose pattern I’d describe as medieval Czech psychedelic — it looked like an Airbnb decorated by Baba Yaga. This was the perfect place to begin my taxidermy essay, I figured, sitting at the kitchen table while my husband taught a morning poetry workshop for the next two weeks. I described Deyrolle’s white peacock, spiny anteater, stuffed zebra, and intricate diagrams of fluted French mushrooms. A couple of pages into the essay, however, I moved away from the dead animals and toward other aspects of mortality, including my phone call, several years earlier, to a suicide hotline and the context for that desperate gesture. Writing about the taxidermied animals at Deyrolle — their bodies, their mortality — made me consider my own body, my own mortality. The etymology of the word taxidermy, too, began to reveal itself as a potential metaphor to which I might return in future essays: taxis (“arrangement”) and derma (“skin”) — “an arrangement of skin.” The act of arranging seemed to speak to the art of the storyteller or poet while the image of skin began to resonate as a metaphor (for family members, friends, lovers, animals, poems, stories, the different selves we inhabit in a life).

I didn’t plan to write about my breakdown when I started what I thought would be a meditation on a Parisian shop of oddities. In fact, I was so horrified by the essay’s pivot from taxidermy to my scandalous personal business that I put away the draft for an entire year. I finally returned to the essay, though, revising the piece so it began with the phone call to the suicide hotline. The unexpected swerves in metaphor and narrative in “An Arrangement of Skin” reminded me how much I value these sudden associative leaps, how they make writing an ongoing process of discovery.

“I didn’t plan to write about my breakdown when I started what I thought would be a meditation on a Parisian shop of oddities.”

VS: I’m wondering what your feelings are about perceived truth-content in writing poetry, and how those feelings might have carried over, or perhaps changed, when writing personal essays. We don’t ask of poetry, in the way that we do of (most) prose, that it be designated as “true,” whatever that word might mean, or “fictional,” whatever that might mean, but — though I’m not really a poet — it does seem that a poem in which the writer is using “I” is presumed by many readers to collapse any distance between the writer and the poem — eliminating the possibility that “the speaker” of the poem might be someone altogether different from the writer of it — and thereby shifts the poem into the terrain of autobiographical writing. A distillation of this (rather knotty) inquiry might be something like, How, if it all, does the expectation that the content is “true” affect your process in writing both poems and personal essays? Do you feel like there are strictures — or, conversely, immunities — that present themselves in either form in this regard?

A moment that comes to mind here — and it’s one that I really love — is that scene in your essay “The Goliath Jazz” in which you emphasize the ways in which, over the course of the essay, you’ve been thoroughly misremembering details about a character from your past, and how that misremembering has calcified into a species of “fact” that both you and the essay itself now have to confront, to dislodge.

AJ: The self is always my subject in a personal essay, even when I’m writing about taxidermying a raccoon or examining the fairy tale “Bluebeard” or considering the directions wisteria spirals. In “The Goliath Jazz,” an essay about a guy I knew who ended up murdering his sister, the problem I encountered while writing the essay (learning a certain detail I’d taken for granted as a “fact” was actually a distortion of memory) opened into the piece’s deeper subject. Why had I remembered things this way? Questioning my own contradictions and limitations became just as urgent to me as reckoning with a curly-haired choirboy from my past who grew into a knife-wielding murderer.

As a poet, I used to get cranky when people made assumptions about autobiographical content in my work. Like they weren’t giving me credit for having an imagination. I’ve learned to take this particular form of naiveté as a compliment, though, as I hope it has something to do with tonal authority: a certain matter-of-fact attitude my poems’ speakers often take toward the strange or macabre. Recently, an established author emailed me to say that he liked a poem from The Atheist Wore Goat Silk (the one you mentioned earlier: “Upon Asking the Cashier at Kroger to Scan That Old Tattoo of a Barcode on My Forearm”). I could immediately tell, from the way the writer talked about the poem and from certain details he shared with me, that he believed the poem’s dramatic circumstance was entirely autobiographical. He was convinced that I’d once gotten a tattoo of a barcode on my forearm, based on a grocery store coupon, and that my body had rung up under the clerk’s scanner, ten years later, as a sweet potato. I love that this outrageous scenario seems at all plausible. And this writer’s total faith in possibility charmed me.

The Fabulist and Fantastic Edges of Contemporary Southern Women’s Poetry

VS: If I can follow that thread a bit further, I’d love to hear your thoughts about some broader questions regarding genre. It seems to me that we’re getting closer and closer to a place where it’s universally agreed-upon that genre distinction is mostly useless to begin with; if we’re not at that place yet, then perhaps we’re at a place wherein the lines between genres have never been more flexible or blurry and the forms themselves have never been more capacious and undiscriminating, and this is good. (I’m reminded here of that great Eula Biss line: “I think genre is as much a lie as gender is.”) I am, however, interested in how you specifically — having written three collections of poetry prior to An Arrangement of Skin — navigate genre.

Is it an interest of yours to trouble what an essay might look like or how it might function? For that matter, I could ask the same about your intentions in writing poetry. The poems in The Atheist Wore Goat Silk are mostly propelled by narrative, and evoked in me the kind of readerly experience that perfectly executed flash nonfiction does.

I’m also curious to know if there are other writers whose work is often designated as genre-defying — either by the writers themselves or by a readership — that you felt instructed by in composing this collection.

AJ: Although I worked on An Arrangement of Skin for five years, I wrote over half of the essays in a stretch of focused attention during the last year. I began to see the shape of the collection coming together and that clarity and excitement galvanized me. During this time I read English poet and nonfiction writer Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk, which combines aspects of grief memoir, environmental writing, and literary criticism. I loved Macdonald’s lyrical prose style — all those striking metaphors, images, internal rhymes, and assonance — and I admired her book’s structure. As a writer who often works in the braided form on the scale of the essay, I felt a kinship with the way she weaves personal, literary, and historical threads in her memoir. So H Is for Hawk was an important book for me as I completed my nonfiction collection.

I’m especially drawn to the work of memoirists who, like Macdonald, began as poets. I admire Maggie Nelson’s fluid interweaving of theoretical inquiry and personal anecdote in The Argonauts, for example, as well as the fascinating intertextual resonances between her poetry collection Jane: A Murder and her courtroom narrative/memoir about sexual violence, The Red Parts. Mark Doty, Nick Flynn, and Mary Karr started out as poets. Nabokov, too. I like to read his dazzling autobiography, Speak, Memory, slowly, as I would a book of poetry, savoring his imagery’s rich synesthesia. And, of course, I always read poetry. When I was a young writer, reading Larry Levis’s collections Elegy and The Widening Spell of the Leaves changed the way I structured time in my poems. His approach to orchestrating motifs, repeating images, and braiding temporalities helped shape my sensibility.

I also seek out essays in journals and magazines to which I subscribe as well as collections of literary nonfiction. The growing audience for essays should be encouraging to us all — just look at the broad interest in Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams and Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist. I’ve admired a number of other recent essay collections, too, such as Eula Biss’s Notes from No Man’s Land, Charles D’Ambrosio’s Loitering, and Aleksandar Hemon’s The Book of My Lives.

VS: In your experience writing these essays, did you ever feel as though the form was granting you access to do something — with language, with movement, with engaging the content, etc. — that a poem might have made difficult? I suppose the reverse also interests me; if anything you found possible in writing poetry felt distant or even inaccessible when writing these essays.

AJ: While I enjoy employing narrative strategies in poetry, most of my poems tend to fall farther along the lyric end of the spectrum. They’ll often evoke a particular moment rather than narrate a series of events, and they’ll use fragments of stories to suggest partial glimpses of larger ones. In a poem, I’m interested in concision, brevity, mystery, and metaphor. I want to make a single clear gesture. In the essay I’m interested in being more expansive and engaging with narrative in a more sustained way. I hope to push the lyric capacity of my prose — in terms of figurative language, imagery, and sound — though I’m working in a more capacious form, which gives me room to sprawl out, to tell more of the story.

Then there’s the issue of subject matter in the poems and essays. If I’m writing a poem called “As a Child, My Mother Took a Girl Scout Field Trip to the Men’s Ward of a New Orleans Prison” (this is an actual poem title and the event did happen), I’ll feel free to make up a bunch of details about the experience and maybe exclude others that seem too crazy (like the fetuses preserved in jars of formaldehyde that my mother recalls seeing on shelves in the prison’s basement morgue). If I wanted to write an essay that involved my mother’s Girl Scout prison adventure, I wouldn’t go nuts and make up a bunch of details the way I would in a poem, but I’d find other areas in which to be inventive: with metaphor, with syntax, with a surprising countertheme. I’d also think: Include the fetuses.

VS: Entering into the framework of understanding you bring to bear on taxidermy and then revisiting Rachel Poliquin’s The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing — a book that really stunned me when I read it only a few months before reading An Arrangement of Skin, so it was a thrill to see you engaging with it — I was detecting certain parallels between taxidermy and autobiographical writing. Specifically, I was thinking about the fraught nature of what one might call the ontological impulse or impetus to have something taxidermied or to write autobiography. For as much as taxidermy is about preservation of some kind — the urge to freeze time, to keep alive what isn’t, to suffuse something gone with a sense of continuance, to make oneself a kind of god — it also strikes me as a way to make that very same thing end; to force a coda of one’s own fantasy over reality. And I wondered if the same couldn’t be said of the nature of autobiographical writing, too. The taxidermied object is, as you so wonderfully put it, “arrested in time and posed to emulate everlasting life.” When I landed upon that line I thought — well, hey, that’s the essay in a way, too, right? I admire that the essays don’t bully the reader into forced recognition of the possibilities of these parallels, which seemed to me, so excited as I read, a mark of authorial restraint that I often associate with poets. But speaking outside of the essays, I wonder what was going on in your thought process with regard to all of this? In “Birds 101” you write, “The taxidermist’s ability to hide the seams — those threads that join dead flesh to fabric — is what makes the vanished animal flutter back to life.” Do you feel you were seeking something similar in writing certain of these essays?

AJ: Yes, I do. I discovered Poliquin’s cultural and poetic history of taxidermy, The Breathless Zoo, about five months after I’d written my collection’s title essay in the Baba Yaga apartment in Prague, so when I finally revisited the draft I brought to it a keener awareness of taxidermy’s storytelling and lyric capacities. Her argument that seven “narratives of longing” compel people to create taxidermy seemed to describe many of the reasons that drive writers to make art, too: “wonder, beauty, spectacle, order, narrative, allegory, and remembrance.” So Poliquin’s notion of the taxidermist-as-storyteller or lyric magician inspired me to Google “taxidermy classes, Los Angeles” and locate Allis Markham’s taxidermy studio Prey, where I took my Birds 101 weekend workshop and my Mammal Shoulder Mounts class. After reading Poliquin’s book, I also kept thinking of Rilke’s famous poem about the unicorn (“the creature that doesn’t exist”), in The Sonnets to Orpheus, in which he suggests that the mythic beast can become a living creature if people nourish it with the strength of their belief. “They didn’t feed it with corn,” Rilke writes, “but always with the chance that it might / be.”

“Desire drives taxidermists, it drives writers. I think the erotic dynamic of lack — I had this, I want it back — has everything to do with why and how we create literature.”

So you’re right to describe the imaginative drive of the taxidermist and personal essayist as a similar forcing of a “coda of one’s own fantasy over reality” in that we project our longings onto our subjects — a posed starling, a powerful memory — and use these narratives to tell essential stories about ourselves. Desire drives taxidermists, it drives writers. I think the erotic dynamic of lack — I had this, I want it back — has everything to do with why and how we create literature.