Books & Culture

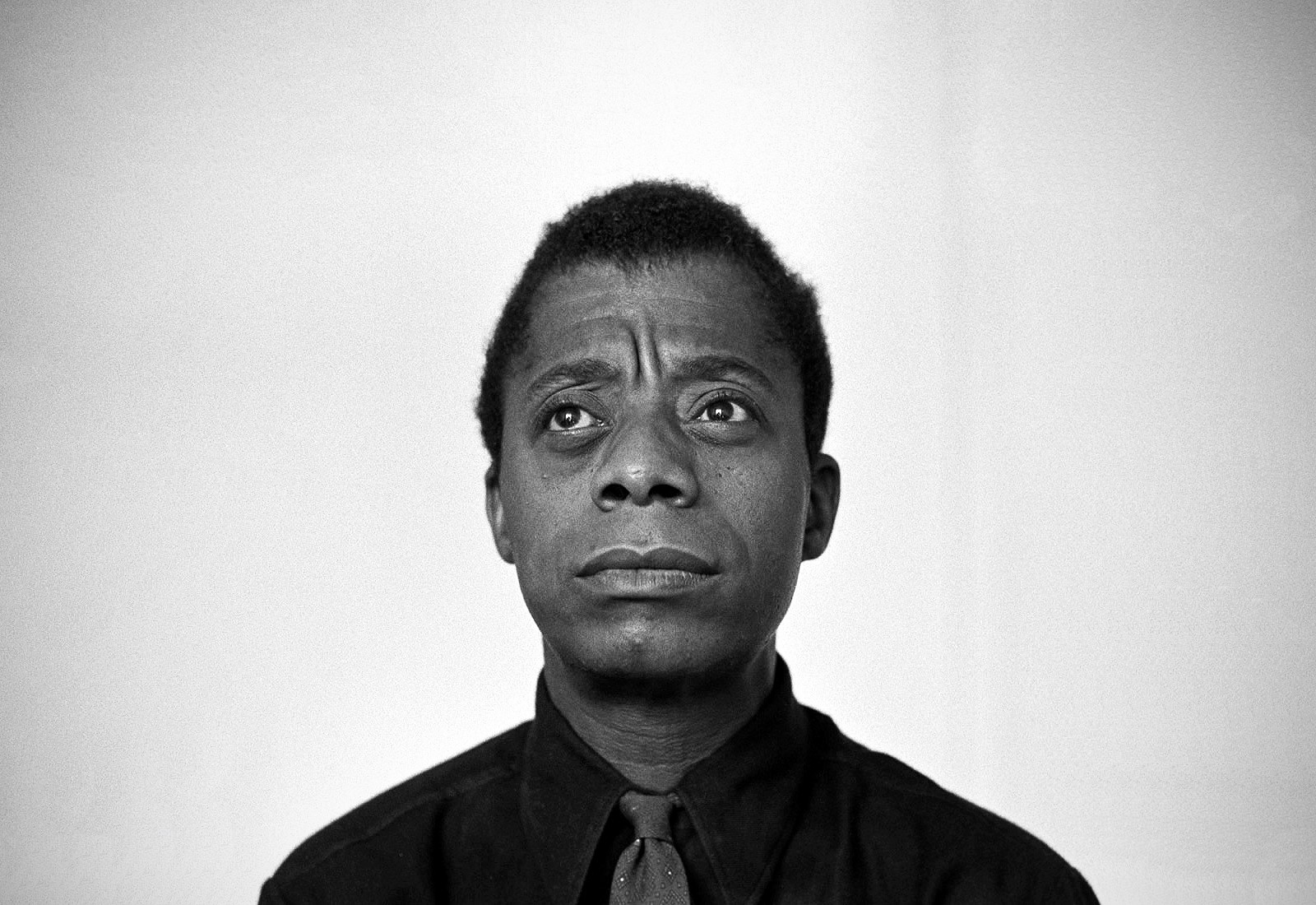

James Baldwin’s Black Queer Legacy

What the documentary ‘I Am Not Your Negro’ does and doesn’t get right

James Baldwin: But that demands redefining the terms of the western world…

Audre Lorde: And both of us have to do it; both of us have to do it…

James Baldwin: But you don’t realize that in this republic the only real crime is to be a Black man?

Audre Lorde: No, I don’t realize that. I realize the only crime is to be Black. I realize the only crime is to be Black, and that includes me too.

The year is 1984, and two now-legendary Black queer icons debate, one mansplaining to the next. Their conversation will end up published in Essence Magazine, three years before James Baldwin’s death and eight years before Audre Lorde’s. Baldwin confidently states that in America being a Black man is the only “real” crime, thereby delegitimizing Lorde’s struggle as a Black queer woman dealing with many systems of oppression. For all of his poignant work on white supremacy as a poison to us all, he sometimes failed to recognize his privileges while centering his own struggle as a Black man in the fight for liberation. And yet, as a writer who lives queer Blackness in a very heteronormative white world, Baldwin speaks to me in a way no other writer has.

Baldwin’s brilliance as a political essayist is unmatched, and Raoul Peck’s 2017 documentary I Am Not Your Negro gives an important glimpse into the thought process of a visionary. Based on the scant thirty pages of a manuscript by Baldwin, unfinished before his death, the film introduces him to new audiences and also serves to remind us that ain’t shit changed. Both the greatest strength and weakness of the documentary is in Peck’s mission to ensure that “every single word was pure Baldwin.” With the intention of telling the story of the deaths of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcom X solely using Baldwin’s notes, the director succeeds by overlaying Samuel L. Jackson’s narrated reading with a series of contemporary and archival visuals.

However, as some commentators such as Dr. Eve Ewing have suggested, to create a full-length documentary out of a series of loose unfinished pages is a risky endeavor, one that creates a slight unease for the viewer. The film points to the chalk outlines of Medgar, Martin, and Malcolm not as discrete and unconnected events but as part of one world, and yet falls short in explicitly tracing our government’s history in repeatedly targeting Black revolutionary thinkers. What actually sticks out in the film are the modern shots of #BlackLivesMatter protests, footage of lily-white women, and the interview clips from Baldwin’s prime that serve as a testament to his oratory prowess.

Peck’s faithfulness to the original manuscript may at times be thrilling, but this is also a documentary where the FBI provides the only voice to speak on Baldwin’s sexuality, rather than Baldwin’s own. I Am Not Your Negro cites an official Federal Bureau of Investigation document which refers to Baldwin as a “suspected homosexual.” This brief memo is the sole mention of his non-heterosexuality, and of his non-compliance with the expectations of Black men in this country. What might seem like an insignificant biographical notation should actually be read as an act of violence, considering how the Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) worked at that time to literally and figuratively assassinate activists, community organizers, and public intellectuals such as Baldwin. The efforts by former major players like J. Edgar Hoover and Richard Nixon did not end there, however, as demonstrated within the current Movement for Black Lives on more than one occasion. But it follows a long history of erasure by historians to make those who are marginalized even at the margins appear more palatable for Black, white, and heterosexual audiences alike. It is in light of these details that we must renew our focus on how Baldwin’s Blackness was queer, and his queerness Black. Much as his Blackness informed his work so too did his queerness, and there is no way — as the film attempts — to separate those two identities from each other.

Even considering my qualms, I am lucky to say that in the last year I have consumed more accurate representations of my full Black queer self through films like Moonlight and parts of I Am Not Your Negro than I have in my entire life. I do not intend for that to stop, but encouraging the production of Black queer intellectual work is a different endeavor than taking responsibility. The enduring writing by Sojourner Truth in the 1800s and James Baldwin in the 1900s can finally lose some relevance in the late 2010s when we push for new work and also hold ourselves to a higher critical standard. Although we should celebrate Peck for successfully summarizing and historicizing white supremacist violence in North America, producing a well-received documentary that only gives a partial accounting of Baldwin’s work is simply not enough.

This spirit of loving critique for Peck and loving defense of Baldwin’s life comes out of my recognition of both the author’s irreplaceable brilliance and of his culpability as a blueprint for mistakes which we continue to make, as evidenced in his debate with Audre Lorde. It’s true that when looking at the entire Black queer literary canon, few artists have embodied Baldwin’s unrestrained sociopolitical commentary. Even putting myself in the same theoretical arena as Baldwin requires balancing ego against imposter syndrome. But as a fellow Black queer male essayist, I have an awareness of how the architects of popular narrative can reshape our history to diminish or dismiss those less favorable aspects of our identities. We would do ourselves a disservice by allowing Baldwin’s immortalization as an untouchable pillar to stop us from assessing the ways in which we collectively entrench the very systems of oppression that necessitated such raw work in the first place. Avoiding the subject forces us to keep quiet about those parts of ourselves that have long gone unspoken. The only way we embody Baldwin is by honoring our truth.

I was first introduced to James Baldwin, by name only, in 2013. I had been planning to study abroad in Cape Town, South Africa, with the intention of creating art in the week just before classes began. A white community college professor of mine — the head of the acting conservatory I had attended right after high school — suggested that I do a one-man show on James Baldwin. I had never heard of him, and as I collected more ideas for the “what to create for the Grahamstown National Arts Festival” bucket, Baldwin remained little more than a name. I think there was a nagging sense in my mind of, what does this white man know about Black queerness? This was at a time in my life where I did not openly consider myself a writer and, further, it was not clear to me why I should care. Looking back I believe his suggestion was a combination of benign intent, problematic projection, and a profound difference in cultural capital.

It wasn’t until 2015 that I finally read The Fire Next Time while on a plane. Much like I Am Not Your Negro director Raoul Peck, the sense of recognition was such that I could not stop thinking about Baldwin after reading only a few words. I devoured the last bit of the thin novel as I flew into Baltimore for an HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and advocacy conference. Encountering that book upon attending an all-queer, all-Black conference brought me even more clarity than had the experience of the beginnings of #BlackLivesMatter in 2014, while I was living in a former Apartheid state. Or rather, the encounter with his work built on what I had already begun to see, once I’d stepped outside my own privileges.

I returned home and began to understand that for most of my life I was the negro whom Baldwin had spoken about. In many ways white societal expectations had groomed me to be “their negro,” through my socialization as a child of military parents and a keen sense of awareness on my mother’s part. There is a profoundly cruel irony in successfully protecting Black children from the ill-will of humans who see them as inhuman, by teaching them to be respectable negroes. Many Black children unintentionally adopt a politic of respectability by forcing our younger selves to silence pride in the face of structural and interpersonal racism. We want to survive, meaning that we sometimes ignore when we are not paid as well as a less-qualified peer. We want to survive, meaning that we enter interracial relationships without critically interrogating the elephant in the room — the toxic pervasiveness of white supremacy. Studying abroad on a scholarship accelerated my personal process of decolonization, the anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like expanded my global political consciousness on Blackness, and James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time cemented the dawning truth that he so eloquently states in the film: “white is a metaphor for power.”

More importantly, Baldwin taught me a lesson that stood contrary to everything else I had learned in life up till then. As Black folks we do not tell our business, and we definitely do not disparage fellow Black folks in front of white people. In fact, our business is really only safe at home, where white and non-Black people of color are out of eye and earshot. Not only does whiteness have a way of using truth and vulnerability against the Black body, it also has a tendency to appropriate Black pain, Black joy, and Black ingenuity. Black folks are not allowed to publicly display weakness or incompetence, which may even contribute to suicide rates among young Black boys when the solution lies in the opposite direction, in greater openness and increased mental health advocacy to end the stigma. These are silencing norms preached in many Black communities for the sake of our collective survival. Baldwin defied what I was personally taught when he told all the business, in what read like a single, rugged, run-on sentence.

Externally, white television hosts would invite Baldwin on their talk shows only to dismiss him, in spite of the furor of audience applause frequently shown in the documentary. And it is clear that Baldwin’s precise diction aided in his presentation to the white folks who could — and did — just as easily hate him.

The shift in the audience came after the November 17, 1962 issue of The New Yorker, where Baldwin penned his “Letter From a Region in My Mind.” He had published in a white periodical that largely pandered to that very same audience, although the difference was he was actually speaking not only to white folks about themselves, but to Black folks about ourselves. The essay, republished later in The Fire Next Time, details the minutiae of his meeting with the Honorable Minister Elijah Muhammad, who held an enormous amount of power at the time not only among Black Muslims but also many Black Americans searching for a leader. Under Baldwin’s pen, the suggestion was that not everyone who is our skinfolk is our kinfolk. This risky candor — which came through in the piece’s many biting observations, such as that “Elijah’s power came from his single-mindedness” — taught me the necessity of intra-community critique and self-reckoning, particularly as an openly queer Black man with mental illnesses.

Writers like Baldwin, Biko, and Lorde eventually became, for me, portals of rediscovery. I had always loved to read, but it was only in poring over their work that I saw my full self on the page for the first time. My personal narrative became less “special,” but at the same time more robust when not overrun by the suffocating gauze of whiteness. I highlighted or underlined damn near every word of The Fire Next Time — I’d found a written testament to so many of the feelings I had experienced in my own life, but which had never before been reflected back to me. It was like being under the same mentorship that Baldwin had guided his nephew by, when he wrote that, “You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a n*gger. I tell you this because I love you, and please don’t you ever forget it.” Whereas the value of Biko was in expanding the bounds of the diaspora, Baldwin gave me something else: a quiet permission to be Black, queer, vocal, and critical.

I Am Not Your Negro is America’s opportunity to peek into Baldwin’s boudoir for the first, fifth, or fiftieth time. The author’s mission, to heal us from the ongoing perils of whiteness, is a message for all ages, nationalities, abilities, sexualities, races, ethnicities, and gender identities. Although Peck disappoints by prioritizing the FBI and generally downplaying the question of Baldwin’s sexuality, we have writers like Dagmawi Woubshet who have written extensively about such mistakes, pointing out that slack. We need more authors who force the audience to chew on what we have to say like it’s the gristle in their steak, and who also make us wrestle with our own responses. For me, Baldwin held up a daunting — if blurry — mirror that revealed the essayist, critic, and intellectual inside myself that I never knew existed. And I firmly believe that when Baldwin wrote that he thought “all theories are suspect, that the finest principles may have to be modified, or may even be pulverized by the demands of life,” he also meant for that to apply to how we tell our stories and define ourselves. I see myself as more than just a conduit for his political musings, a frame for his work, or a retreading of the past. The greatest effect the film can have is to get people to go back and read Baldwin, to reread and critique him, and to start on documenting their own narratives. There is no other way.