interviews

How a Japanese Novella about a Convenience Store Worker Became an International Bestseller

Talking to the translator of Sayaka Murata’s “Convenience Store Woman” about a novel that defies expectations worldwide

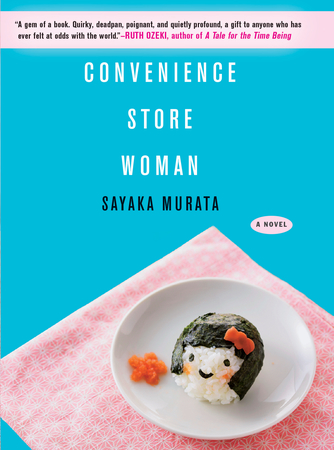

I f you’ve been looking in many bookstore windows recently, you may have seen a tiny hardcover whose sky-blue and cherry-blossom pink jacket features a rice ball made to look like a woman’s head on a plate. I recommend picking it up. Convenience Store Woman is Sayaka Murata’s eight novel, but the first to ever be translated into English. Following a hugely successful Japanese publication — Murata won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize and over 600,000 copies sold in two years — the novel went on to sell in seventeen languages in translation before finally coming out in the U.S. and U.K. last month.

How does a literary novel become an international sensation? Murata’s English translator Ginny Tapley Takemori sees the novel’s success as due, in part, to its “broad appeal”; it is written in everyday, approachable language, so that it might attract fans of manga and anime as well as the literary types, whereas “normally there isn’t much crossover.” And there’s also the fact of the book being knock-you-off-your feet good, sucking you wholesale into the strange brain of its narrator, Keiko Furukura, and carrying you quickly through a smartly constructed plot. But most of all, the book is “just so unexpected.” It’s shocking in Japan, but perhaps even more so to a foreign readership, defying all our stereotypes of Japanese literature and Japanese women.

Keiko is single at 36, and happy. She is proud of her extreme proficiency at a job typically staffed part-time by students. The store gives Keiko comfort and purpose, but it goes much further than that. At times it feels like a religious temple, glowing into the night; at others the store is an extension of Keiko’s self, its needs vibrating in her very cells. In one of many exquisite passages, she reflects:

When I can’t sleep, I think about the transparent glass box that is still stirring with life even in the darkness of the night. That pristine aquarium is still operating like clockwork…. When morning comes, once again I’m a convenience store worker, a cog in society. This is the only way I can be a normal person.

A single female narrator, uninterested in sex, completely focused on work that doesn’t constitute a “career,” is a departure from the norm in Japanese literature as much as it is in English. “I don’t think there’s been anyone, at least that I’ve come across, quite like Keiko,” Takemori tells me, “especially in not even missing having a relationship!” Sexuality as a woman is central to Murata’s work, and her novels often feature a lot of sex — though it isn’t necessarily pleasant. Murata is interested in the bizarre pressures society puts onto women. In her newest novel, out this summer in Japan, she is quite explicit: “She sees society as this big baby factory. When you become an adult you become part of this factory to create more humans.”

Takemori’s pet peeve is English editions of Japanese novels featuring elegant, frail-looking Japanese women on their covers. “The image of Japanese women in the U.S., the U.K., and elsewhere is usually quite dutiful, sexy, a bit downtrodden by men. It’s a fantasy.” So here is Keiko: “she’s not attractive, she’s not interested in sex at all — it’s just not on her radar — and she is working to live, in a very unglamorous job. It gives a different view of Japan all together.”

The beating heart of the short, haunting novel is the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart. We enter Keiko’s world in the din of the morning rush: door chimes, advertisements ringing over the intercom, store workers yelling their greetings to customers, scanners beeping, items rustling, high heels clicking. “A convenience store,” we find, “is a world of sound.”

In convenience stores, restaurants, and shops of all kinds in Japan, store workers call out stock phrases, practiced in unison before work each morning. The greetings are so particular and so ubiquitous that no English correlate quite fits. Takemori decided to leave “irasshaimasé” — literally “welcome” — untranslated: “I decided, well, readers aren’t stupid. They can cope with one Japanese word.” She crafted other phrases to sound as formulaic as possible: “Certainly. Right away, sir!” “Thank you for your custom!” You don’t think when you say these phrases, she tells me; you just say them.

Literary translation is both a creative endeavor and a long and impossible series of problems needing solutions. Even if the language itself were your only concern, it isn’t possible to take something directly from one language into another, word for word, particularly between languages that function as differently as English and Japanese. But it’s not just the words that need to be carried over the gap. As Takemori puts it, a translator must recreate the novel’s “effect” — its atmosphere, voice, and impact on a reader.

This is where academic and literary translators divide. Academics tend to prioritize a more exact translation for scholarly purposes, whereas freelance translators like Takemori are more willing to play with the original in order to capture its impact on the reader. “By trying to be too faithful to the original,” Takemori believes, “you can actually betray it.” Convenience Store Woman is often shockingly funny. “There are parts that almost had me spitting out my coffee when I first read it, they’re so funny.” An exact translation — or as close to exact as possible — would be difficult and bewildering to foreign readers, necessarily riddled with footnotes. The humor would fall flat. The utter strangeness, distance, and charm of Keiko’s voice would be lost.

An exact translation — or as close to exact as possible — would be difficult and bewildering to foreign readers, necessarily riddled with footnotes.

So you get creative. You make a way in English for a voice that’s doing something that hasn’t been done before, even in Japanese. It’s a daunting task. “But that’s what I love about it,” Takemori says. I ask her how she did it, how she captured both the endearing and the creepy in the novel’s atmosphere. Like any art form, of course, there isn’t an easy answer. “I just had to keep plugging away at something, you know, like this is a bit flat, it’s not shocking enough… When you finally do get it right, you know you’ve got it, and that’s a really nice feeling.”

Reading Convenience Store Woman feels like being beamed down onto foreign planet, which turns out to be your own. Takemori confirms that the experience is the same in the original. “Sayaka Murata is shocking. Through this very strange character’s eyes, you see society in a different light. You know, what people think is normal is really not normal at all.” Keiko often sounds like a researcher, taking notes on her species:

My speech is especially infected by everyone around me and is currently a mix of that of Mrs. Izumi and Sugawara. I think the same goes for most people. When some of Sugawara’s band members came into the store recently they all dressed and spoke just like her…. Infecting each other like this is how we maintain ourselves as human, I think.

The morning I finished reading Convenience Store Woman, I walked around for hours in a haze, my mind eerily caught within Keiko’s voice. I took some pride in my productivity that morning, tapping away at emails like a small cog in the machine. I felt an inch apart from the racing life of the city in front of me, as if behind a pane of glass. I asked Takemori if she felt something similar while living immersed in Keiko’s voice, in the process of translating. “Certainly I started looking at things in a different way, seeing little details that I hadn’t noticed about Japanese society. I’d always just taken convenience stores for granted. I hadn’t even thought about them.”

Reading Convenience Store Woman feels like being beamed down onto foreign planet, which turns out to be your own.

But Takemori didn’t find herself as disoriented as I did. She reflects that as a foreigner in Japan, she already lives with “a certain distanced perspective.” She will never see things the way she might have if she’d grown up in Japan like everyone around her. I remark that this might have primed her to be Keiko’s medium—an outsider translating an outsider—and she agrees. Though, laughing, she adds: “I don’t think I’m quite as much of an outsider as Keiko.”

Sayaka Murata, the author, could easily be seen as an outsider herself. She writes from 2 a.m. until 8 when, until recently, she would go to work at a convenience store, which she found to be a useful anchor in her day before returning home to keep writing. In an interview with the New York Times, Murata credits the store as an antidote to her former shyness: “I was instructed to raise my voice and talking in a loud friendly voice, so I became that kind of active and lively person in that circumstance.” These days, she is close with a number of other prize-winning, radical young women writers, including Risa Wataya and Kanako Nishi. It’s worth mentioning them here because, though they’re celebrated in Japan, they aren’t well known elsewhere. Which brings us to the great gap in the English-speaking world’s knowledge of Japanese literature — and why it took so much and so long for one of Sayaka Murata’s novels to make it into English.

The Tale of Genji, widely considered the world’s first novel, was written by a noblewoman and lady-in-waiting, Murasaki Shikibu, early in the 11th century. Ever since, women have had a place in Japanese literature, which quite plainly has not been the case in English. The major prizes, the Naoki and the Akutagawa, are consistently awarded to women and men in equal numbers. Meiji-era short story writer Ichiyo Higuchi became the third woman to be featured on a yen note in 2004. Today, Japan is experiencing a great boom in extremely popular young women writers. Takemori shows me a 550-page volume of writing by women, published recently by the literary magazine Waseda Bungaku, which sold out in a week.

But most of those young women writers aren’t making it to America. Much, much less literature gets translated into English than the reverse, to begin with. But of the books that do make it into English, from all languages, the vast majority are written by men. This makes some sense in the history of Japan, Takemori explains: Japanese literature really began making it into English during the American occupation after World War II, thanks to translators like Donald Keene. The Americans in Japan during the occupation were in the military, Takemori points out, “and mostly guys!” The trend those guys began has proven doggedly persistent. Today, outside of Japan, we know of Haruki Murakami, Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki — but besides Banana Yoshimoto, we might struggle to come up with another female author’s name.

This extreme disservice to the talent and vision of Japanese women writers is something Takemori is on the campaign to change. Last November, inspired by a worldwide movement among translators to create more visibility for women writers, she and fellow translators Allison Markin Powell and Lucy North held a translation conference in Tokyo: “We were deliberately provocative in calling it Strong Women, Soft Power.” It was a smashing success, with tickets sold out in advance. “It got a lot of people talking. I think we’ll be seeing more Japanese women in translation from now on, actually.”

I can only hope that this is true. In the meantime, may we buy out bookstores’ stocks of Convenience Store Woman, and yell Sayaka Murata’s name from the rooftops.