Interviews

How Do You Advocate for LGBTQ Rights When Your Culture Has No Word for Gay?

How Do You Advocate for LGBTQ Rights When Your Culture Doesn’t Have a Word for Gay? Trifonia Melibea Obono on using literature as a weapon for change in Equatorial Guinea

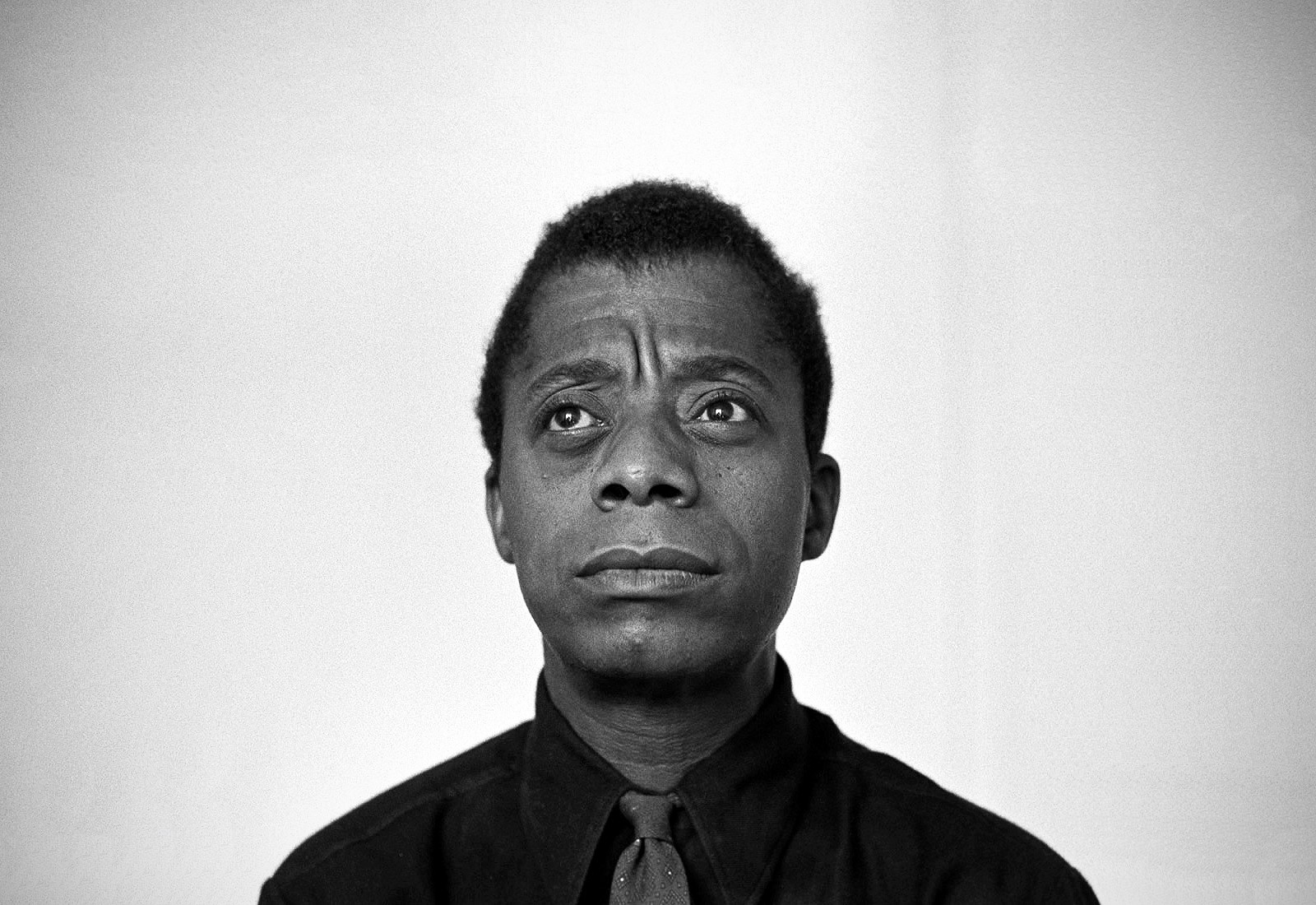

Trifonia Melibea Obono is an Equatorial Guinean writer and activist, who has published three novels (Herencia del bindendee, La bastarda, and La albina del dinero) and a short story collection, Las mujeres hablan mucho y mal, which won the 2018 Justo Bolekia Boleká international Prize for African Literature.

I translated into English her novel La Bastarda, which is the first book by a woman writer from Equatorial Guinea to be published in English. It is the coming of age story of a young Equatoguinean girl, Okomo, in her search for her father, who she’s never met because her mother died in childbirth and he had never paid the bride price, so Fang tradition holds that she belongs to her mother’s father and his tribe. La Bastarda is the story of Okomo who falls in love with a woman and (along with various other characters) challenges the patriarchal, polygamous Fang culture.

I spoke to Obono about advocating for LGBTQ+ rights in Equatorial Guinea.

Lawrence Schimel: Homosexuality in Equatorial Guinea is seen as “something white people do,” something alien to the African reality, even though that is far from the truth. How does our understanding of sexuality change in an international context?

Trifonia Melibea Obono: Sexuality continues to be a taboo subject in Equatorial Guinea for most people. And the reason that homosexuality is attributed to white people is simple: in this country, all phenomena that people don’t understand are attributed to God, witchcraft, or white people. It’s the habit here to blame the white people for many things, for everything that goes wrong. These same attitudes and behaviors are reproduced throughout black Africa.

Things will change over time, with the implantation of democracy and efficient educational systems in black Africa, and the real opening of our nations to the international world on a cultural level. We will understand then that we black people are the equal to whites, and that sexual-affective orientations are something human.

My novel advocates for the right of women to have a sexuality.

LS: In La Bastarda, you comment that a word for “lesbian” doesn’t even exist in Fang, although there is a term to denote gay men: “man-woman.” Are there people in Equatorial Guinea who are trying to change and expand the languages (as well as the culture)?

TMO: As of now, the concept “lesbian” is a neologism in the ethnic languages of the country. That’s how women who love women are called. Nonetheless, due to the conceptions held about homosexuality (that it’s a habit of white people, demons, evil spirits) the definition that’s given to the concept “lesbian” is very pejorative. Very derogatory.

In Guinea, we speak six or seven languages, plus English and French, and now Portuguese has been incorporated as well. The homophobia and machismo from Western cultures that accompany the term “lesbian” have augmented Guinean attitudes toward lesbianism. In many parts of the world, LGTBI women don’t just need to confront homophobia, but also machismo and the patriarchy.

The sexuality of the Fang woman doesn’t exist. Not even the heterosexual woman has a right to her sexuality, the only thing expected of her is reproduction, that’s it. My novel advocates for this right for women: the right to have a sexuality.

The homophobia and machismo from Western cultures that accompany the term “lesbian” have augmented Guinean attitudes toward lesbianism.

LS: In La Bastarda, the characters who don’t fit within the heteronormative society wind up creating new models of families and communities. Do you think that literature can change society? On the one hand, your novel makes visible certain realities that aren’t otherwise expressed or documented in your country, and on the other, it serves as a guide for Equatoguineanxs searching for ways to live their identities.

TMO: Literature is a weapon of change. Literature doesn’t lose time, each work is a new story, each work is a challenge because we writers have a responsibility: to create characters, consider problems of society, and propose solutions.

La Bastarda makes visible various problems: violence against women, homophobia, polygamy, child abuse, family rights, mortality of mothers in childhood, corruption, poverty, etc. One element in the novel that seems very positive to me is the forest. The forest represents harmony, freedom, a society tolerant of diversities. The forest is the Guinea of the future, it is a new country.

LS: In your novel, you touch briefly on one of the most serious problems for lesbian and bisexual women in Equatorial Guinea: being forced by their tribe and/or their families to be raped until becoming pregnant. Can you talk more about that?

TMO: The forced pregnancies of LGTBIQ+ women in Equatorial Guinea is an important issue that must be confronted. Because women “in this non-African situation” aren’t covered under the fundamental laws. Besides, people say, there aren’t any cases. They tell me: Maybe some you’ve discovered, knowing how much you exaggerate when you talk about feminism, these ideas of the white people that you brought back from Spain. For now, there also isn’t any money for “these white people things.”

LS: What authors — both within Equatorial Guinea as well as outside of it — have influenced and nourished your understanding of sexuality? And of feminism?

TMO: Guinean books don’t touch on the question of sexuality directly. I have been very affected by the gender roles that women play and the humiliations they suffer, from the first page to the last in the works of Ecuatoguinean literature. Ekomo, the novel by María Msue Angüe, marked me very strongly in this regard.

On the other hand, growing up among Fang women and men (my father and mother are both Fang) helped me to be a feminist. Within me, these women have sowed the seed of a person who will fight for and defend herself and her rights. Now that I’m older and a writer myself, I can see why the discourse of works like The Second Sex (by Simone de Beauvoir) and Sexual Politics (by Kate Millett) resonated with me from the outset.

LS: What was the first book you read about diverse sexual-affective identities?

TMO: When I wrote La Bastarda, I had not read about feminism nor sexual-affective diversity. But I had made love with another woman. I had made love with a man.

Literature is a weapon of change. Each work is a new story, a challenge because writers have a responsibility: to create characters, consider problems of society, and propose solutions.

LS: You just won the Justo Bolekia Boleká International Prize for African Writing for your book of short stories Las mujeres hablan mucho y mal (Women Talk a Lot and Badly). As a writer, what difference is there for you when you write a short story versus a novel? What does each format offer you to tell the stories you want to tell?

TMO: The stories are my therapy in the morning, at night and at noon. The poor things. They don’t love me now, I know. But they help me speak with my surroundings, they listen to me. That’s why I still have some balance. Now that I’ve just answered this question I will write another story, and shortly I’ll revive.

The novel is my traveling suitcase. It holds me for hours, days, months, speaking with the characters and forgetting for a moment that I was born in Equatorial Guinea without the option to choose; that I am a woman without having chosen to be one, that I am not heterosexual in a world with a dominant heteronormative culture.

The novel is the kidnapping of a woman from nowhere, caught in the tam-tam of the repression and the silence of how badly the economy is.

LS: Given the realities in Equatorial Guinea that there are no publishing houses in the country nor bookstores that sell books, do you write in a different way knowing you need to publish with publishing houses outside your own country?

TMO: The lack of publishing houses is a barrier. If you are an Equatorial Guinean who writes, first you need to tell yourself: “Hey, woman without a land, land without publishing houses nor bookstores, where do you think you’re going? Stop! Look around you. What do you see? Nothing. There you are. Nothing.”