Interviews

How to (Inadvertently) Write a Novel About Depression

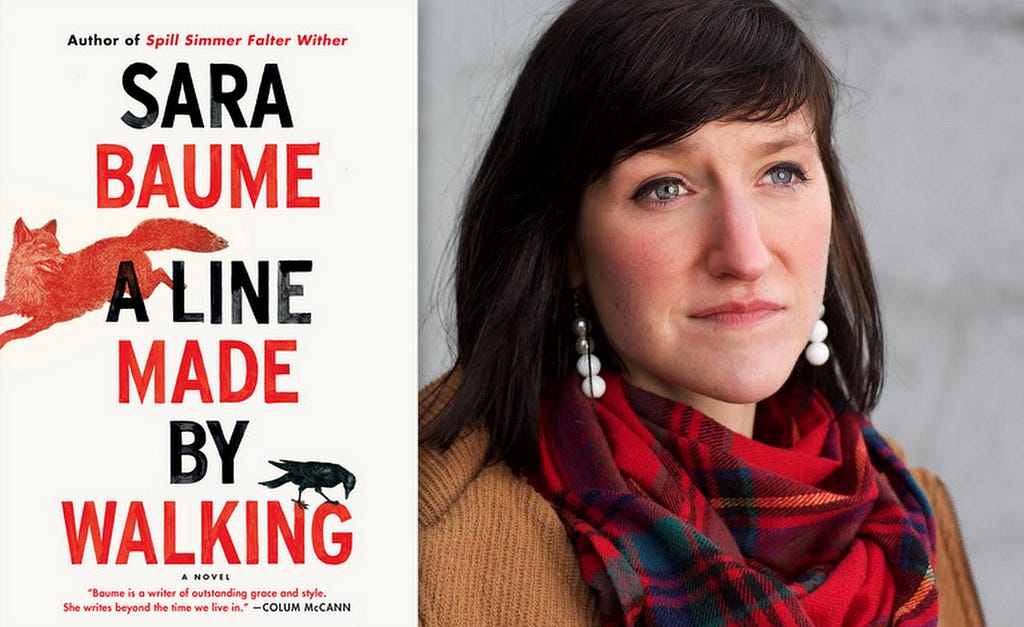

Sara Baume on the creative non-fiction that transformed into a novel about conceptual art and the workings of a “troubled mind”

Sara Baume’s award-winning debut novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, told the story of Ray, a curmudgeonly old man who finds an unlikely companion in a mangy mutt named One Eye. Having a soft spot for both grumps and dogs, I was immediately drawn to the book’s premise. Yet more than the plot it was Baume’s sentences which riveted me; they were quiet yet poignant, mixing unexpected observations about humanity with gorgeous, often tender, descriptions of nature. Her new novel, A Line Made by Walking, may have a different protagonist, but luckily her literary style remains the same.

A Line Made by Walking tells the story of Frankie, a twenty-something sculptor who, struggling with depression and disillusionment, drops out of art school in Dublin and moves to her deceased grandmother’s house in rural Ireland. (Baume herself went to art school before getting her M.A. in fiction at Trinity College.) As the months pass, Frankie takes photographs of dead animals, tests herself on the details of endless works of art, drinks wine, and watches celebrities discuss their mental issues on TV. This last action is one example of the way that Frankie tells us the story of her depression; elliptically, a series of small clues embedded in how she sees the world. These loaded observations — cooking broccoli as a mark of sanity, a stolen bicycle as proof that humanity is crap — expose her profound estrangement from her art, from the world’s expectations, and from herself.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Baume over email about creative non-fiction, her obsession with conceptual art, and portraying mental illness on the page.

Carrie Mullins: There are more autobiographical elements in this book than in your first novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither. Apart from the obvious point that you’re closer in age/gender to Frankie than Ray, you’re also trained as a visual artist. How different is it to write a book whose protagonist is closer to your own reality? Have readers approached the work differently?

Sara Baume: Line started several years ago as a short piece of ‘creative non-fiction’ about a period of my life spent living alone in my dead grandmother’s empty bungalow in rural Ireland. This was during an economic depression, about two years after I finished art school. I was unemployed and increasingly disillusioned and Frankie’s voice draws heavily from those feelings of confusion and despair. Some details remain true, but many more are invented, and stepping back to look at Frankie now, I find her perplexing, even a little cruel. She is me, and not me, but then I’d say exactly the same of Ray in Spill Simmer.

When it comes to readers, I’ve found that, with Line, they are much more likely to ask whether or not it is an autobiographical novel, whereas with Spill Simmer, people are most inclined to ask how I went about — as a young woman — writing in the voice of a much older man. Ray is as much me as Frankie is, because, to my mind, a person is most essentially defined not by age or gender but by experience. Ray is me in the smallest details of his life, in his feelings, in the things that interest and illuminate and frighten him.

CM: Even when she can’t be bothered to eat more than a chocolate bar for dinner, Frankie tests herself to name artworks on a particular subject, from blinking lights to flowers. It was fascinating to learn about these pieces, and I was struck by that word, test, because it’s so active and outside Frankie’s general behavior. How did this recurring element come about? How did you choose the actual works?

SB: Well, first off, the novel is named after an artwork by Richard Long. A Line Made by Walking was an ‘action’ undertaken in 1967 when Long was still a student in St. Martin’s School of Art in London. He caught a train out of the city, and in a field, walked up and down and up and down in a straight line until his footsteps had worn a visible track through the grass, then he documented the site in photographs. It’s just one of roughly seventy artworks which, at intervals throughout the novel, Frankie prompts herself to remember. Each one is a work she learned about in art school, and she sets herself the task of recalling them partly just because she’s afraid of forgetting and wants to feel as if she is continuing to learn in spite of the fact that her formal education has come to an end, and partly as an attempt to find meaning and direction in the so-called ‘real’ world.

When it came to selecting the artworks, it was important to me that each rose naturally to mind in accordance with the sights and objects Frankie stumbles across, the places and situations she finds herself in. I would not allow myself to struggle to call them to mind, or hammer them in where they did not rightfully fit.

And so I was, naturally, drawing from what I already knew — and liked, and remembered — my own frame of reference. I’ve always had an obsession with — and fascination for — conceptual art, and more specifically, the period dating from, roughly, the 1960s up to the noughties. This was a really vibrant, radical, experimental period — taking in modern movements from Pop, Performance, Installation, Minimalism, Land Art, and so on.

My Year in Re-Reading After 40 #5: The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

CM: You paint such wonderful visual images of creatures — crows, foxes, even slugs — and they feel like a seminal part of your work. What draws you to them?

SB: I grew up in the countryside, and live again now in an even wilder place than the one where I grew up. The fields and trees and sea beyond my desk are a constant source of fascination, companionship and influence, and nature has become a theme which is central to my writing. Just recently I’ve read a handful of books which seem to be treading the ground, beautifully, between novel, essay, artwork and ode to nature — The Outrun by Amy Liptrot, H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald, Things That Are by Amy Leach, perhaps — and I’d love to think that Line has some territory in common.

“The fields and trees and sea beyond my desk are a constant source of fascination, companionship and influence…”

So Spill Simmer was structured around the seasons and Line is structured around a series of photographs I took over the course of a couple of years. Each shows a dead creature lying where it fell and as I found it, and each of the ten chapters is named for the creature, from ROBIN through to BADGER. In June 2009, I travelled to Gorzów Wielkopolski in western Poland to take part in a group exhibition in a disused orphanage, and there I showed the photos alongside little creature figurines which I’d carved out of balsa wood. I don’t know exactly what it is about these photos which makes me return to them again and again — one on its own isn’t interesting, but I find that there’s something tremendously poignant about the prints all together.

CM: When you’re trying to sell a novel, the conventional emphasis from agents and publishers is on plot, even for literary works. (What’s the hook? Will the pace be enough to capture an audience? et-soul-crushing-cetera.) Your novel has successfully dispensed with much of the traditional idea of plot. Was that a conscious decision as you were writing? Was it ever hard to get buy-in, even for a second novel?

SB: Well, for me, getting published was a somewhat unusual process. With Spill Simmer, I never dreamed any of the bigger publishers would be interested. I didn’t have an agent and I only sent it out to a handful of small, indie presses. It got picked up very quickly by Tramp Press, a new Irish publisher, which I guess would be similar to the like of Dorothy Project in the US. It did really well here at home, and so then I signed with an agent and the rights sold on to bigger houses in the UK and US, and in translation. I signed a two-book deal pretty early on, with just a first, rough chapter of Line. I expected, at every stage, that I’d be told it was a completely unmarketable novel, but I seem to have been blessed with really brilliant, open-minded editors on both sides of the Atlantic.

CM: This is a story about a young woman struggling with depression, and it doesn’t end on an arbitrarily happy note, which I appreciated. Can you talk a little about the ending, and about depicting depression on the page?

SB: Strange as this might sound, I don’t think I was really aware, during the process, that I was writing a story about depression; it was certainly never my intention to start a conversation about mental illness. Here in Ireland, there is no shortage of such conversations in the media, and Frankie is frankly bored by them. Though she is clearly sad and struggling to cope with adult life, she angrily resists labels and medication, choosing to deal with her sadness and disillusion in atypical ways and in defiance of professional advice. But would she have been better off doing as she was told? It’s a novel, not a polemic. I was more interested in the way a troubled mind flits and the things it alights upon — I’ve reached no particular conclusion.

I chose to end with the description of an artwork, and it took me some time to decide upon the right one.