Interviews

Imprisoned in Egypt for His Writing, Ahmed Naji is Finally Free

The author of “Using Life” on his new beginnings in exile

No one foresaw that Ahmed Naji would be imprisoned for his novel. After all, no author had ever been subjected to arrest for morality reasons in modern Egypt, and as Naji himself says in this interview: “My writings are not political.”

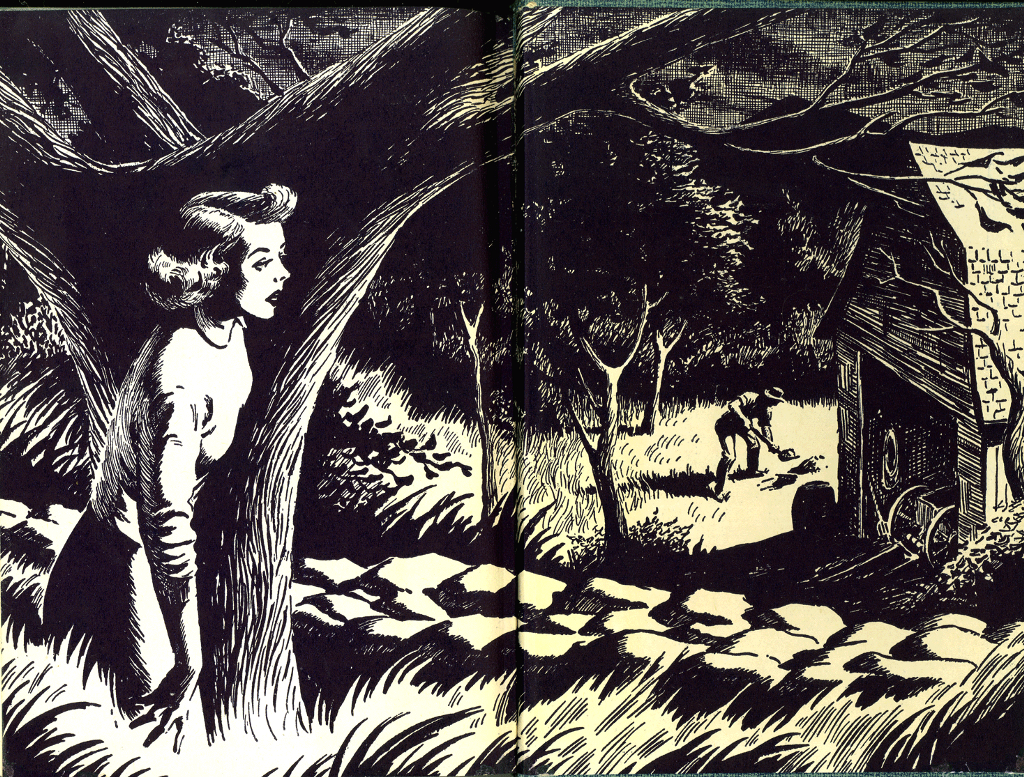

The novel in question, Using Life (illustrated by Ayman Al Zorkany and translated from Arabic by Benjamin Koerber), reads like a colorful account of someone having a lovers’ spat with the city in which he’s lived all his life. That is to say, the book is full of intimate familiarity, occasional tender scorn, and a fervent curiosity toward city and man’s entwined fates that is also somehow coolly detached.

Opening in near-future, post-apocalyptic Cairo, Using Life combines graphic novel elements and quirky characters to produce a portrait of a man making the best of life in a city on the verge of disaster. It is a rollicking read, at times zooming into dizzying detail (for example, a section illustrating Cairo’s various inhabitants), other times hurtling into madcap, breakneck action (secret societies! Ninja assassins!). Above all, the book is a bold depiction of a person pushing against the boundaries of their given life.

The novel passed the inspection of Egypt’s censorship board and was lauded by critics in Egypt and the wider Arab world. Then the unexpected began. In 2015, a private citizen lodged a complaint against Naji after an excerpt from Using Life was printed in Egyptian magazine Akhbar al-Adab. The private citizen, a lawyer, claimed that he suffered heart palpitations and a drop in blood pressure after reading passages from the excerpt describing cunnilingus. State prosecutors then took these claims seriously, and as a result Naji was sentenced to jail on charges that he “violated public modesty”.

As mentioned, his ordeal is extraordinary, marking the first time in modern Egypt that a writer has been incarcerated for their fiction. Zadie Smith puts it this way: “Naji’s prose explicitly confronts what happens when one’s fundamentally unserious, oversexed youth dovetails with an authoritarian regime that is in the process of tearing itself apart.” While imprisoned, Naji was granted the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write award, which was accepted on his behalf by his brother.

In 2016, Naji was released from jail but subjected to a travel ban. In May of this year the ban was finally lifted, and Naji was able to leave Egypt. I caught up with him and translator Benjamin Koerber over email shortly after Ahmed Naji’s arrival in America.

YZ Chin: Glad to hear about the travel ban being lifted! How does that change things for you as a writer, if it does change anything?

Ahmed Naji: I’ve finally been able to travel and leave Egypt. I’ve now moved to the United States, where my wife lives, after we’d spent a full year separated from each other by the ocean and passport inspection officers.

I spent the two years after my release from prison in Cairo, and they were some of the most difficult years for me as a writer. First of all, I was under strict surveillance, and I was not allowed to organize any events or cultural activities. We failed to get official approval for the book launch event for my short story collection, which was published after I got out of prison. Only the Goethe-Institut, which is connected to the German Embassy in Cairo, offered to host the event.

Following the advice of my lawyers, I decided to keep away from publishing until the case was over. For the first time in my life, I felt the real weight of censorship. Even worse, I didn’t know what the red lines were. One time, I published an article on the band Mashrou’ Leila. Lo and behold I get a call from a friend who’s close to the security services, chastising me for the article and telling me they considered it a provocation since Mashrou’ Leila supports the Arab queer community, and that this sort of behavior could negatively impact my case and travel ban. Leaving Egypt now allows me to finally breathe and think freely, to test out my ideas, and reexamine everything that’s happened. I’ll finally be able to enjoy the company of my wife and the friends I have here.

But it also raises complicated questions for me: Is this to be a temporary, or permanent, departure? Am I to become a writer in exile? What does exile mean, now? If I stay here for a longer period, what will I do? What will I write about? Will I keep writing for an Egyptian audience, while living in America? Or will I assimilate to the new society and culture, change to writing in English, find a new ethnic or religious identity to subscribe to, and thus turn into one of those writers that talks about “Islam”, “the oppression of women in the Orient”, “the Arabs”, “terrorism”, and other such topics that captivate American audiences? For now, I’m trying not to think about all that, but I know I’ll have to face those questions soon.

For the artist to protect himself from confrontation with the institutions of power and all their violence, he has the three options that James Joyce prescribed for the writer: “lying, exile, silence.”

YZC: I’m very happy to hear that you are reunited with your wife. Sounds like you’re understandably at a difficult crossroads writing-wise. I get the reluctance to become a mouthpiece that caters to American appetite or biases. Are you concerned America will change you or pressure you in ways beyond that pigeonholing?

AN: I’m always ready for change. So far, I’m optimistic and open-minded about this American journey. My first concern is to learn — to understand this country, to take it all in and figure out its rhythm — and through this I’m sure I’ll find the right place for me. I’m lucky because I have a large number of friends here who are writers or work in the cultural or political fields. They’re providing me with support, and the keys to understand the nature of the scene here.

YZC: Do you think there’s also a risk of being pigeonholed as “the writer who went to prison?” As opposed to, say, “the writer who writes about finding joy in a depressing city and the fearsomeness of killer ninjas.” What would you like to be known for as a writer?

AN: I hope to be known as the writer with a thousand faces. I’d be very receptive to any of these labels or classifications. The writer’s challenge, in my opinion, is his ability to open up to the world, to change, to embark on new adventures, and to create new works. The writer that went to prison, the writer who writes about a depressing city called Cairo, is the same writer that might tomorrow write about intrigue and power play in Washington, D.C. Or he might write about a girl’s education in America. Anything is possible. My appetite’s ready for all trials and experiences.

Two days ago, I was talking to Yasmine [Naji’s wife] about something, and said, “As exiles, we don’t have the luxury of holding on to a lot of memories.” The thought terrified her. It hadn’t really set in yet. “Oh my god, we really are exiles,” she said. I tried to lighten the both of us up by focusing on the few real benefits of exile, like the unbearable lightness of being, and the freedom to remake one’s self and one’s image. Exile provides the opportunity for a new beginning, and there’s nothing more thrilling for me than new beginnings.

Exile provides the opportunity for a new beginning, and there’s nothing more thrilling for me than new beginnings.

YZC: As a writer who grew up in an atmosphere of state censorship, I struggled for a long time with self-censorship. Have you had any previous run-ins with the Egyptian censorship board? How do you grapple with the possibility of censorship when you write?

AN: I think a big part of writing is struggling with, and figuring one’s way around, the many forms of censorship that exist. The political censorship exerted by the state is a concern of course, but I never confronted it before the trial. My writings are not political and I was not interested in clashing directly with the state; I hadn’t thought that sex worried them very much. The greater pressure, the form of censorship that I feel impacts the writer more, is the censorship of society and the family. This form of censorship burrows under your skin, without you ever feeling it. It sometimes becomes impossible to confront or to expose, like the censorship that imposes itself under the name of political correctness.

YZC: That rings true for me, the existence of censorship that never gets registered. So you’re saying there needs to be constant self-exploration to understand the pressures that are placed on us. In that case, I’m curious if you think it’s possible to deliberately cultivate our influences as a countermeasure, like garlic against vampires? If so, what is or would be your garlic?

AN: In such circumstances, the garlic can be prepared a number of different ways.

1 — Listening closely to one’s own personal desires and pleasures, however forbidden or prohibited they might be, however useless they might be to society or the “wheel of production”. No impulse should be suppressed, nor should you run after it like a teenager. You just need to listen to it, then take your time polishing it, until the desire turns into a will.

2 — Don’t put too much trust in psychology or self-help doctrines. Do you really think all these books, programs, and talk shows want you to succeed? Do you really think that the secret of happiness can be sold with a holiday discount? Believe me: except for your mother, no one’s really concerned about your happiness and self-interest.

3 — Whatever you do, don’t let them catch you. In Egypt we have a nice little proverb that says, “Fuck the government but don’t show them your dick”.

4 — Always practice in front of the mirror first. A few days ago in D.C., there was a small demonstration of Neo-Nazis and white people. It was really quite small. Facing them was a counter-demonstration of mostly African Americans and anti-Nazis, which was huge. The Nazis, surrounded by police, were waving flags; they were vastly outnumbered by the counter-demonstrators. In spite of this fact, they were marching with full faith in the protection offered by the police. Their demonstration ended before it began, and they quietly left amidst the shouts of the counter-demonstration. The question I kept asking myself was, “What were they [the Nazis] thinking? Did they consider what happened a victory for them?”

YZC: There’s an interesting passage in Using Life where the character Ihab thinks about art: ‘Might not the “truth” of art conflict with its duty? That is to say, the duty art has to be functional?’ It certainly seems that to censors and some readers, art has a duty to uphold morals. What are your thoughts on the duty of art?

AN: Morality is not constant, it’s constantly changing. Otherwise, we’d still have the morality of the nineteenth century that held African Americans in the cotton fields and women in the kitchen. Permanence and stability are illusions. The world and human consciousness are in permanent motion, and the writer is part of this motion. The power of art lies in its ability to strip off the moral veil that society’s institutions impose under the pretext of stability or observing morality. When that happens, art performs its role vis-à-vis the individual by upsetting the ideas and convictions that one has been raised with. Art also performs its role vis-à-vis society in helping to change the prevailing morality.

Of course change doesn’t happen easily. The art that performs these roles puts itself in open confrontation with the institutions of power and all their violence. For the artist to protect himself, he has the three options that James Joyce prescribed for the writer: “lying, exile, silence”.

The power of art lies in its ability to strip off the moral veil that society’s institutions impose under the pretext of stability or observing morality.

YZC: When I saw David Bowie listed in your novel’s Acknowledgements page, I immediately thought it was very apt because Using Life is such a rollicking and at times surreal read. Best Bowie song?

AN: [I’m Deranged]

YZC: Using Life flirts with fantasy and magical realism, and of course graphic novels. Do you see more possibilities and avenues for expression in blending genres? Will you continue working across genres?

AN: I hope so. One of the faces I’d like to be known by is that of fantasy writer. Comics for me are my eternal dream. I’m a big fan of comics. None of my current projects involve comics, but I have a file full of dozens of stories and ideas that are just waiting for the right artist to execute them. I have the ambition to write a massive graphic novel, which I hope to realize some day.