Books & Culture

In Memory of Brazenhead, the Secret Bookstore That Felt Like a Magical Portal

Michael Seidenberg, who died this week, created a real-life space that was like walking into a book

In a popular trope present most often in YA novels, a character finds a secret key to another world. The key is rarely literal. More often, it’s an action as banal and everyday as leaning against a train platform barrier, walking into a phone booth, or looking for a winter coat in the back of an old wardrobe, that sends our hero out of the familiar and into something stranger and better. It usually happens by accident, on a day like any other day.

These through-the-looking-glass plot devices are meant to offer the reader hope, to invite us to feel part of the story. By depicting entry into an imaginary world as something on which anyone could stumble by tripping over their own feet one morning, it allows the reader to believe that the same magic might happen to us, in our own dull, repetitive, familiar lives. We are always just one wrong step, one turn around one corner, one missed exit away from falling sideways in Narnia.

For many of us who were lonely kids, books act as portals. We are always still hoping to tumble through them into elsewhere.

This longing for secret doors to another world is largely seen as a childish way to access literature, as childish as admitting that you still read books because you love them, and for no more lofty or sophisticated reason than that. Plenty of people, plenty of serious readers and writers and critics, don’t engage with books this way at all. But for many of us who were bookish, lonely kids, and grew up to be bookish, awkward adults with lives based to some degree around reading or writing, this is a desire that we never quite scrub from our hearts. Even when we’re no longer reading books about portals, the books themselves act as portals. We are always still hoping a little bit to tumble through them into elsewhere.

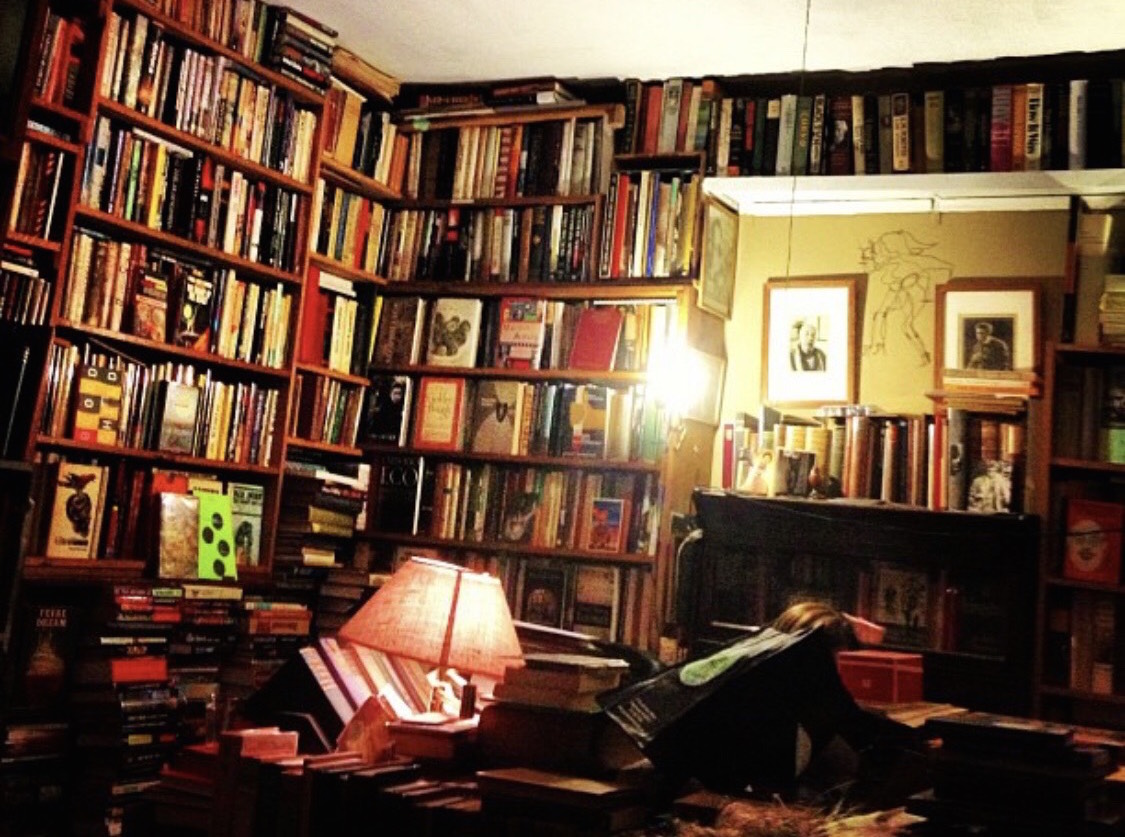

Brazenhead bookstore was up two flights of unremarkable stairs in an unremarkable small apartment building on 84th street, down an unremarkable grimy hallway lit by the same awful, ubiquitous fluorescent overhead lights that preside over the conclusion of every late-night house party in New York. The door was painted a blue-ish grey-ish color like every other door in a New York apartment building that’s been painted and repainted so many times that it can’t really be any color at all. The first time I visited was in January of 2011; a friend had invited me to a literary salon at a bookstore, an invitation that sounded like dozens of other events happening every night in New York. We knocked on that unremarkable door and it cracked open, belching yellow light and smoke and laughter, and then shut behind me before I had a chance to notice where I was. I looked around and for one brief, nearly-hysterical moment, I thought: this is it, I’ve done it, I fell through the wardrobe and got into another world. The other, better, wilder, secret place had in fact always lived just at the edge of this one, and finally I’d knocked on the right door, performed the right series of accidental choices, and arrived in the place the books promised.

Brazenhead was, as you probably already know since it was the worst kept secret in New York City, a speakeasy bookstore run by the legendary Michael Seidenberg, who passed away earlier this week. At the time I first visited, it was housed in what had once been, and was technically still supposed to be, Michael’s rent-stabilized one-bedroom apartment. Books covered the room, only grudgingly making space for people to walk and stand between them. The walls were lined from floor to ceiling with books, some of them in shelves and some of them just accumulated into teetering piles. They covered all of the windows, making it perpetually nighttime in Brazenhead, a place that kept insomniac hours and only came to life at night anyway; if you emerged from Brazenhead into daylight, it was because you had stayed there until the next morning. There were no clocks; a friend called time inside Brazenhead “bookstore casino time.” There were two front rooms in which the books were divided with meticulous disorganization into sections by genre, which included New York Literature and Science Fiction next to each other near the front, and Pornography in a highly popular heap near the back. Behind a small curtain and furthest from the door there was the First Editions room, which was smaller and darker and more secret than the rest. It had a little cushioned bench, a very dim lamp, and shelves of first editions, mostly novels, some rare, some signed, some just weird. It was where people went to hook up during parties, because they didn’t know everyone knew what they were doing back there, or maybe because they did.

For one brief moment, I thought: I’ve done it, I fell through the wardrobe and got into another world.

Since Brazenhead was an illegal business, the only way to visit was hearing about it by word of mouth. It was best to buy books if you could, and it was advisable to bring whiskey to share with whoever else might be there, and most importantly with Michael. Some nights there were fifty people there, some nights there were two. You never knew quite what kind of party, or what kind of evening you would walk into. It was secret but not exclusive: The price of entry was merely that you had to want to be there, that you had to want to sit around talking shit with Michael about whatever ridiculous topic Michael wanted to talk about, that you had to think a night where you were allowed to lapse out of conversation and sit in a corner taking books down from shelves for 45 minutes was a good time. It was a place that attracted weirdos and losers and social climbers and grown-up awkward kids who still wanted to live inside books, and it is where I met or became close with many of my very favorite people.

If I say that Brazenhead was like stepping inside a book but for real, it sounds stupid; stuff that is magic always sounds stupid. The belief in it always sounds childish and naive. But the people I knew who frequented Brazenhead, and especially Michael himself, who ran it and had created it and from whom its magic originated and emanated, were anything but naive. We had grown up past the idea of books being somehow enchanted, past the YA novel idea of being special enough to be offered the right accidents. I understood well by the time I first walked into Brazenhead that books were no more magic than a corkboard coaster, a bunch of paper jammed together into a physical object that mostly sat around underneath drinks. But I still carried through my life the hope underneath everything that something big enough, something enough not-myself, would lift me up and carry from away from the essential mundanity of my life, and I continued to seek in books this temporary and artificial escape. That reaching for elsewhere was both hopeful and, like many hopeful things, desperately crushing when it turned out not to be true, one of the many processes of necessary disappointment that propels one from childhood to adulthood.

Brazenhead was the place where it did turn out to be true, where there was another world, not beyond this one, but right here inside of it. When I walked in there for the first time, and every time when I walked in there after that, no matter how bad a mood I was in, what kind of day I had had, what I was worried about, or how drunk I already was from where I had gone before, I always felt just the tiniest bit transformed. It was always welcoming in the same way the worlds within books is welcoming, a place that said all those promises of escape might be true.

Escapism in the manner of the bookish kid longing to get away from their own life seems selfish. A lot of adolescent loneliness turns out in hindsight to be selfish, predicated on the inability to heave yourself up out of your own experience and see that other people are in pain, that other people are struggling, that your own difficulties are neither unique nor spectacular, that they do not excuse you from kindness. Eventually, you learn that your pain is not large enough to replace the slow and hard and gentle work of listening to others.

The type of escapism found in books at its best provides an experience of selflessness.

But part of what books can offer, in their portal-worlds, is nearly the exact opposite of the adolescent self-pity that seeks to evade connections with others by hiding in an imaginary world. Reading can temporarily grant us the ability to shake off self-obsessed worries about the events of our own humid little lives. The type of escapism found in books at its best provides an experience of selflessness. That selflessness is not necessarily generous or empathetic, but it is escapist precisely in how it allows us to de-center ourselves. In books, we forget, abandon, or transcend the self for a few hours, dwelling somewhere other than our own small and falsely urgent life.

In a similar way, Brazenhead was a living argument against the idea that the belief in portals, the longing for escape, was childish or naive. That’s not why Michael, who was definitely not a wide-eyed kid trying to find Platform 9 ¾, created the store. He didn’t have some magical or idealistic mission for it; he just didn’t want to leave his house. He wanted to know lots of people, he wanted to hear about what people cared about and were reading, he wanted other people to bring him booze, he wanted in general to live entirely on his own terms. Lots of us who love books have claimed we wanted to live in a bookstore, to hide inside a library and never have to leave: Michael actually did it. But by the force of his belief in the world as he wanted it to be, he built a portal to a place where that live-all-night-and-forever-in-the-library feeling seemed briefly available to everyone who walked through the door. It was a better world, even if it was only five hundred square feet of it. It was a place where the limits, rules, laws, and logistics that bind us, the pedestrian nagging and worry that we are bound to, were left outside—which was, in the end, always the escape I was hoping for when I submerged myself in books. At Brazenhead, going inside books was literal and real.

Michael was a myth by the time I met him, and more so by the time he passed on Monday night. His bookstore could never really stay secret because everyone wanted to know him, and everyone wanted to talk to everyone about how they knew him; I like to think it was because none of us could quite believe he was real, and we were all trying to narrate him into reality, to pin him down into our own stories. Jonathan Lethem, a Brazenhead regular, and a dear friend and former employee of Michael’s, had actually turned him into fiction, basing characters in both Motherless Brooklyn and Chronic City (the which book, my favorite of Lethem’s, always feels to me like it is about Michael more than anything else) on him (his dog is in Chronic City, too). Michael would sometimes jokingly sign copies of these books, implying he was their real author.

Of course, he wasn’t an author, not primarily. He was a beautiful, skilled, fiercely intelligent writer, as evidenced in the “Unsolicited Advice for Living In End Times” columns he wrote for The New Inquiry, which are collected online here and which I truly can’t recommend enough. But his enduring genius was what he created with Brazenhead. If books are seeking to invent imaginary worlds into which one might escape, then Michael authored that portal experience in real life, through his insistence on living exactly how he wanted, and then being fiercely, radically generous with that living, opening up this elsewhere to anyone who wanted to visit. He was a host at a level of genius so great that it created a world.

Michael authored that portal experience in real life, through his insistence on living exactly how he wanted.

I went to Meow Wolf in Santa Fe about a year ago, an immersive art installation piece in a bowling alley that is also a 20,000 square foot science fiction novel. It was, again, that experience of stepping into another world, of submerging oneself in an elsewhere. Meow Wolf is full of literal portals; you actually can lean through a wall and fall into a different place. It made me miss Brazenhead more sharply than I had in years. Brazenhead was this same thing, but the portal led back to the real world. These things, it said, could actually exist. You could actually hide in the library and live there forever. Brazenhead may have felt removed from reality, but it wasn’t. It was a very real place in which I could travel vertically into the idea of books, into the unreasonable desire for a better world, into the early longing created as a reader and as a lonely kid looking for anything that was not myself.

There was a night once when Michael opened Brazenhead just for me and two friends. It was past midnight by the time we arrived. All three of us were heartbroken about failed relationships or unrequited loves. Michael would have been fine with it if we had just sat around in his bookstore and gossiped about our little personal sorrows while we smoked his pipe in the background, but instead we did the thing that people usually did when they came to Brazenhead: We took books down off the shelves and read them out loud. We competed to see who could find the saddest, most absolutely heart-punching poem or prose excerpt to read out loud. It was both a serious expression of our pain, and a mockery of it. Michael listened, and laughed at the right times, and very occasionally offered very gentle no-nonsense advice. We all three of us needed to escape into books that night, and had we all just gone home separately to cry ourselves to sleep, we probably would have individually done just that. But we went to Brazenhead instead. The portal was right here where we lived, a few subway stops away. We slid out hours later into the early sunlight, to go home and sleep through the morning. Nothing was fixed, but I knew I could go back anytime I wanted, I could knock on the secret door that wasn’t really secret, and be admitted into this elsewhere that wasn’t really elsewhere at all.

Brazenhead moved locations since then, the original one on 84th street eventually becoming unfeasible and shutting down. There was a long series of “last” nights there, one last night after another after another for at least a month, and then, eventually, it re-opened. I rarely went to the new location; it some ways I felt I had outgrown it, that it was better to cede it to newer people who needed it more than I did. In some ways I was just too afraid of not knowing anyone, too afraid it wouldn’t be the same. But I always loved knowing it was there. I loved walking around with buried knowledge that I could go back any time I wanted, that I could still knock on the secret door, and trust in the world that waited behind it.

In the days since Michael passed, tributes to him have proliferated online, and at first some part of me felt jealous or possessive, that other people I’ve never even met had loved someone I loved, that they too had known how to lean sideways just right and fall through this reality into a better and stranger one. But I remind myself that these remembrances are what he created; they hold together a world, hopeful and unlikely, that once existed in a room made of books, where there were no clocks and no windows, where it was always nighttime, and the night never had to end.